President Obama’s difficulty in convincing Congress to grant him authority to negotiate the Trans-Pacific Partnership without legislative amendment is a serious setback for his foreign policy agenda. Most commentary on the subject has focused on the trade deal’s likely economic impact — which are not negligible, most importantly for Asian partners like Vietnam, but likely won’t impact the US in discernable ways. Others discuss its geopolitical significance in breathless, but vague, tones. Take this recent NY Times article:

“If this collapses, Pacific Rim countries will be aghast,” said Shunpei Takemori, a professor at Keio University in Japan, the largest economy in the would-be trade zone after the United States. “China is pushing, and if the U.S. just stands aside, it would be a tragedy.” …

“If you don’t do this deal, what are your levers of power?” Singapore’s foreign minister, K. Shanmugam, asked in Washington on Monday. “The choice is a very stark one: Do you want to be part of the region, or do you want to be out of the region?”

As it happens I am working with Sam Brazys of UC-Dublin on some research examining preferential trade agreements in systemic context. What does “systemic” mean, for us? Most studies of PTAs focus on the dyad as the relevant unit of analysis, and look for factors that make it likely that a PTA is created between two economies. Sam and I are treating all PTAs as comprising a global structure, which we render as a network. We believe this is appropriate for a number of reasons, not least of which is the fact that governments view their PTA portfolios holistically rather than as a collection of independent agreements; that’s how China’s Ministry of Commerce portrays their agreements, for example. Methodologically, we believe that the formation of a PTA is conditioned by the existence of prior PTAs. If this is correct, and observations of PTAs are not statistically independent from others, then studying them as if they were independent dyads is very likely to yield biased results.

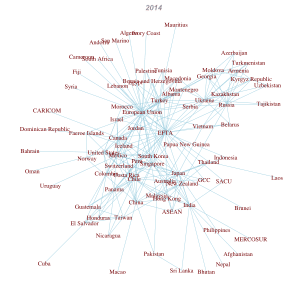

Anyway, this is what the global network looks like as of last year (click to enlarge):

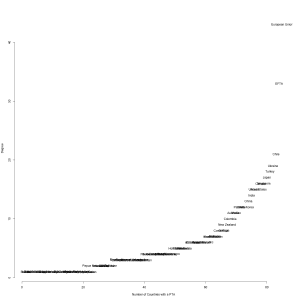

It is a system clearly organized around Europe, which is one reason why the Obama administration is also pursuing closer ties to the EU through the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) deal. The EU and EFTA (European Free Trade Area, comprising Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein) are the most prominent nodes in this network. But there are other clusters that are visible: former communist countries in Europe are tied together, as are many economies in Asia and Latin America. The United States is not poorly positioned within this structure, but it is relatively isolated from it certain communities within the network such as Asia. The US’s position is more evident when looking at some measures of centrality (sorted by size). First, here’s degree centrality, which simply adds up all of the connections a country has in the network:

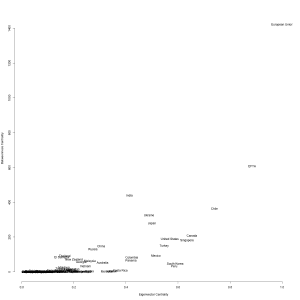

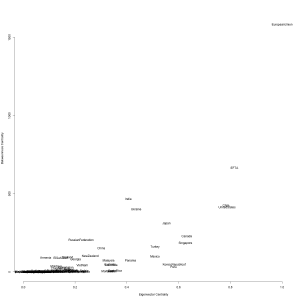

The US is slightly more prominent than India by this measure, and less prominent than countries like Singapore, Turkey, and Ukraine. Alternative measures of centrality reinforce a picture whereby the US is lags behind others in the global PTA network. Here is a graph with eigenvector centrality (higher scores means a node is well-tied to other well-tied nodes) on the x-axis and betweenness centrality (higher scores means a node provides pathways that connect otherwise-disconnected nodes) on the y-axis:

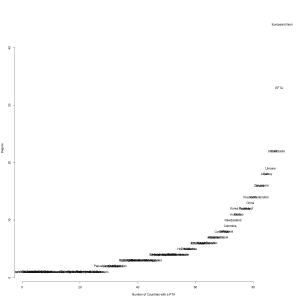

Again: Europe dominates, while the US is in the middle of the pack. Just for fun, I recalculated these statistics to see what the network would look like if TPP was enacted. Here’s the basic degree centrality:

The US becomes tied (with Chile, another TPP party) for third-most important in the network, behind only the EU and EFTA. And here’s what the eigenvector and betweenness centralities would look like:

The US most noticeably improves in the eigenvector score (it moves further right down the x-axis), indicating that TPP would allow it to be more closely tied to the best-tied countries in the system. It also increases in terms of the numbers of paths it provides to connect otherwise-disconnected countries (it moves up the y-axis). Overall, it becomes around the third most-important node in the network, and it would become much better tied to a region — Asia — that it is relatively isolated from now. These ties will become increasingly important as Asia captures a greater share of the global economic, demographic, and security structures.

Why does this matter? Prominent nodes in networks are capable of influencing others. In this case, it would mean that the US would have a much greater role in determining how the global trading system develops over the coming decades. This has implications for the extent to which the US’s preferred policies on a host of issues that go beyond simple economic gains — labor rights, environmental standards, product safety codes, etc. — are on the global agenda. It will make it more difficult for China to pressure its neighbors into over-reliance on partnerships with China for their prosperity and, perhaps, security.

So in terms of US foreign policy strategy passing TPP is practically a no-brainer. Which is probably why Obama is pushing so hard for it, despite his past ambivalence towards trade deals like NAFTA.

Cool post. Thanks!

Is there anything good to read on your second-to-last paragraph (benefits of centrality)? I buy that network position can help some actors in certain policy domains (e.g., as in your bank ISQ paper), but it’s not self-evident to me that states can extract much benefit from network centrality in trade agreements. I can imagine reasonable theoretical arguments, but ultimately this is an empirical question, and I’ve been too lazy to figure out what kind of evidence people have given so far.

So, any reading suggestions?

Hi Vincent,

Thanks. It kind of depends on what you mean. Usually network centrality measures are used to uncover influence within the network, but not necessarily outside of it. So we might want to know if there are “rich get richer” effects — whereby an initial centrality advantage is reinforced over time — or if certain types of connections become more likely under different degree distributions: maybe triads close more frequently, or something. And of course, if you believe that these deals lead to positive material benefits then being a major player in this system could be important for strictly instrumental reasons. A lot of smallish open economies (EFTA, Singapore) and/or those that are at or just above middle-income status (think Chile, Turkey, Ukraine) are more prominent in these networks than I think many would expect. Some of these are questions Sam and I will look at as the work progresses.

Another way to think about it is through the lens of “structural power”, which frequently separates out autonomy and influence as manifestations. If you are prominent in the global PTA system then you are less likely to overly-dependent on any one country; it seems like this is part of why a lot of Asian countries are trying to diversify their PTA portfolios: to reduce their reliance on China. (Other countries are doing deals with China to reduce their reliance on the Western core economies.) And it might make you less dependent on the WTO, which does not suit many countries very well at the present moment.

I agree that it’s more difficult to think about how this might matter for other areas. Does EU prominence in PTA networks give them leverage in negotiations over climate change or currency policy? It’s doubtful. That said, governments act as if they believe that promoting strong trade relationships will help them in other areas. So there could be other positive effects. They will likely be more difficult to observe at any particular point in time, but that’s just another reason to have a sense of what the overall structure of the system looks like.

Thanks, that’s useful.

I keep wanting these network analyses to become less self-referential. If nodes are influential simply by virtue of being central, then why even distinguish between “influence” and “centrality”? We need to step out of the network, and you’re right to point out that structural power is one way to do that.

Side note: I wonder if there are supply chain-related benefits to being a central node. Maybe the increase in bilateral trade that results from a new treaty is small, but the act of positioning yourself in the middle is still worth it.

Technically, nodes aren’t influential simply by being central. Being central just means that a node is in the thick of things. Often being central can confer influence, and different types of centrality may confer different types of influence. But not always, and it’s definitely worth being as clear as possible about what we mean when we use these terms.

While I agree that it is definitely often worthwhile to “step out of the network” I also think it’s worth knowing what the world looks like. A lot of network analysis in poli sci is operating at a fairly basic level because we’ve spent so long in the world of regression that any kind of structural analysis has been neglected. For example, I doubt anyone would be surprised the Europe is prominent in the PTA network. But I doubt lots of people would be surprised at how prominent Chile, Turkey, Ukraine, and India are. Or they’d be surprised by how the BRICS *aren’t*. That’s useful knowledge to have in one’s pocket as you think about what impact these agreements are likely to have.

And, frequently, the network itself is an interesting outcome variable that may be influenced by political factors. (That’s what Sam and I are focusing on modeling for now). We already model the system all the time; we just do it dyadically. For a variety of reasons that might be problematic in ways that network analysis can help fix. So I actually think that in many respects we have a ways to go before we’ve learned all we can about these systems.

Yes, global supply chains might matter in this context. It could also provide a competitive advantage for local producers. There are all kinds of ways in which being at the core of these networks can provide instrumental value. The problem is that it’s often hard to separate structural position from other factors. But that’s always the challenge, isn’t it?

Right, but that was my point: too often (in my view), we just stipulate that centrality gives influence rather than demonstrate it. I guess I’d just like to see more work in which a network feature explains something else than another network feature.

That said, I agree that (a) there’s lots of cool/new/surprising/useful information to be learned with your approach, and (b) what I’m asking for is much easier said than done.

I look forward to reading what you guys cook up.

Gotcha. I think there’s a few things to note. First, inferential network models are much better (both mathematically and computationally) when the network is the outcome than when a monadic attribute is the outcome. That is changing some, but it’ll be probably be awhile before we’ve got everything we’d want. In the meantime we can try to build reasonable models of how the networks form, grow, and evolve. Then, when the technology improves, we should be able to slip the switch.

In the meantime some folks calculate network statistics and then use them as predictor variables in regression models. Zeev Maoz has a whole book doing this. It’s not ideal, because part of the point of using network analysis is to avoid making an IID assumption when you think it’s not appropriate. That said, it can be an improvement over the status quo (whereby network dependencies are left out completely, thus potentially biasing the model). I’ve done it some in the past, and am doing it in another paper or two I’m working on now. Mostly in stuff related to banking and financial crises. I don’t like doing it, but for now there aren’t better options if you think these factors matter.

You can also develop an intuition that builds from the observation of the structure to the realization of the outcome, if you have a reasonable understanding of the structure. That’s what Oatley, Danzman, Pennock and I tried to do in our Perspectives on Politics article. I try to do much more of this in a forthcoming article in Business and Politics as part of a special issue on structural power. The danger with this is that there can be slippage in between structure and outcome, and if you’re relying only on logic to connect the two people (ie reviewers) get antsy. But it can be done, and should probably be done more than it presently is. Part of that, of course, is because there just aren’t that many people using network analysis in IR/IPE. More than there used to be, but it’s still a small club.

In my opinion all of these are better than most of our workhorse regression models. Even more complex spatial and diffusion models are starting to look weaker as we learn more about network dependencies. So I guess I’d say let’s not make the perfect the enemy of the good.

Sold!

While I don’t doubt that passage of TPP would give the US more influence in “determining how the global trading system develops over the coming decades,” as Kindred puts it in the post, the problem is that TPP itself, given certain of its provisions, appears to further skew that system in favor of the interests of pharmaceutical companies and other companies with patent and intellectual property ‘concerns’, as opposed to everyone else. Susan Sell, author of a couple of books on IP (neither of which I’ve read), made that case in her June 12 (2015) Crooked Timber post “Why TPP sucks.”

The IP laws involved in TPP are not extraordinary in US terms. The intention isn’t to protect large IP holders, but rather to normalize trade.

I’m personally for eviscerating IP laws both domestically and abroad, but there isn’t much to fear comparatively where TPP is concerned.