Over on my Facebook feed, there’s a good discussion going on about Adam Elkus’ “The Problem of Bridging the Gap.” Elkus’ post amounts to, quite deliberately, a medium-length polemic against “policy relevance.” That is, he aims to provoke.

For example, Elkus argues that:

It judges the value of academic inquiry from the perspective of whether or not it concords with the values, aims, preferences, and policy concerns and goals of a few powerful elites. Why, if anything, do we judge “policy relevance” by whether or not it helps governmentpolicy elites? Surely governmental elites, politicians, think-tankers, etc aren’t the only people who care about policy! The “policy relevance” model is simply a normatively unjustified statement that political scientists and social scientists in general ought to cater to the desires and whims of elite governmental policymakers.

And:

It demands that academic inquiry ought to be formulated around the whims and desires of the people being studied. One does not see this demand outside of the political science policy relevance wars. No one asks psychologists whether experiments are “relevant” to lab rats because it would be absurd to base research around what the experimental subject wants. Psychologists also do not care whether or not the college students that are paid to populate their experiments find their research “relevant” or understandable. Nor do neuroscientists inquire about the preferences of neuronal populations or biologists the opinions of ant colonies. Yet political scientists ought to cater to a narrow set of policy elites that they (partly) study?

You should go read the whole thing.

Over on my feed, people have made a number of important points:

- Whether the “policy relevance” discussion is really about relevance in the broader sense, rather than simply about serving the needs of officials and other elites.

- The role of large government and EU grants in driving international-relations research in Europe.

- That alternative conceptions of policy relevance might escape Elkus’ criticisms.

- If arguments about “policy relevance” are, at least within the field of international relations, rarely really about “policy relevance.” Indeed, my own view is that people use policy relevance to advance their particular vision of what the field should look like in terms of methods, methodologies, and the prestige associated with studying particular topics.

Anyway, thought the broader Duck of Minerva readership might find this interesting.

(image source, attribution, and license information at the link).

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Daniel invited the participants on the Facebook thread to

post/summarize/move their comments here, and because he’s a friend of mine and

assured me that even a non-professional perspective would be welcome, I’ll take

up that invitation. Also, it seems that no one else did.

A bit about me first. I am *not* an IR scholar, nor even a political science one. I have a BA/secondary ed. degree in Broadcasting and Spanish, and a law degree. Issues of politics and education both interest me a great deal though. Given my background, I come at the questionsraised by “Policy Relevance” from an outsiders’ view, and my chief interest is in what the Academy’s role is in society. I initially posed what I said as a question, but I’ll dispense with that. I have some definite views, so I’ll state them and let others challenge, if they’re so inclined.

I believe that it would be better for the world if policy-makers would evaluate their policy goals in light of what they know about both political/IR theory and their practical experience in governing, as well as their own original insights that grow out of a synthesis of the two. In light of that belief, I think it is a mistake for the Academy to become the “hand-maiden of government.” Doing so not only short-changes leaders who may have a little less hubris than is assumed in the article, but it short-changes society in the future, when it will be governed by new leaders who are just now cutting their intellectual teeth. The Academy is, after all, an educational institution, and that goes not only for instruction, but also for

publishing. For what is the point of publishing academic work, after all, if not to add to the body of knowledge that may be studied, formally and informally.

I’ve been challenged on this point in three ways: 1) Policy-makers aren’t really interested in scholarship, but in finding more effective ways to do what they already want to do, 2) It is a vain hope to believe anything done in the training of undergraduates and graduate-level students will have any impact on those of them who go on to become policy makers given the likelihood that with require 2-3 decades; and 3) There aren’t many students of political science who go on to become policymakers anyway. I don’t believe any of these points is an adequate rebuttal.

In the first place, policymakers have to formulate their goals somehow. Those goals do not come by way of divine revelation, and they are not entirely a product of domestic politics. Marrying their own experience with an understanding of the scholarship will give them a greater ability to see the realistic policy goals available to choose from, and both the costs and likelihood of success of any particular goal. Taking current policy-makers’ preferences as a given may be a decent short-run strategy, but it gives no thought to the future or the possibility of using scientific inquiry to influence it.

Second, whether one expects the training of undergraduates or graduate-level students to have any value 20-30 years in the future depends on what one is attempting to train them to do. If the training is only to provide knowledge of the factors underlying current IR problems, then perhaps the criticism is a valid one. But if one trains them to think deeply about IR problems and give them to tools to work on IR problems we haven’t even envisioned yet, one can reasonably expect a modest benefit when they are actually faced

with such future crises.

On the last point, it may be sufficient to note that the last four Presidents earned degrees in the social sciences in areas that are highly relevant to International Relations. President Obama has a degree in political science with a concentration in International Relations; President George W. Bush had a degree in History; President Clinton had a degree in Foreign Service, and George H.W. Bush had a degree in Economics. It seems to me that

those in a position to advance scholarship in International Relations should assume that their work may well influence future generations of leaders.

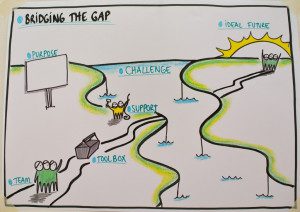

As PI for a Carnegie “bridging the gap” grant last year I have had the opportunity to interact with this group. I absolutely agree with Dan that some have tried to use policy relevance as a way to enhance their preferred method or tribe. And Adam Elkus’ point that efforts to be relevant are frequently directed at policy elites is fair. On the other hand, the Carnegie Corporation did award a significant grant for our project (which sees policymakers as everyone from civilian neighborhood groups to NGOs to multi-national corporations). Our “Denver Dialogues” blog (https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/denver-dialogues/) has posted dozens of analyses by social scientists and policy makers (broadly construed) of non-state actors and their impact on policy. Our most recent post by Celestino Perez (https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2015/09/01/soldiers-in-dark-times-military-education-ethics-and-political-science/) also looks at the responsibilities of those making military policy to be aware of the social science relevant to their decisions. We are not alone. In addition to pointing out some notable problems among policy relevance discussions, I think it is also important to note – and pay attention to – the outliers.

There is some truth in this post, to the extent that there is a pressure to write the thing that scholars think practitioners want to hear so that policymakers can wield the academic’s work as proof of what they already wanted. I think any self-respecting academic has to be aware of that pressure but not succumb to the temptation to just regurgitate policy talking points.

I think the point that is missed here is that the direct dialogue between policymaker and academic is often mediated by journals, staffers. If I write for a think tank, am I writing for policymakers? If not, I’m writing for audiences who think that they know what policymakers want to hear but it may not. If you are directly writing on contract for a policy outlet, you may get more specific instructions on content, like a RAND type study, but I think academics if they are writing on important topics that are of interest to government can question the premise of what policymakers want and still be relevant. In many cases, whether it is funding from the DOD on a Minerva grant or writing for a think tank (of which I’ve done both), I’ve never gotten direct steers from them to push me in a direction I don’t believe in. I’m also not afraid to question the basic foundations of current approaches (or at least that’s what I tell myself).

I re-read Elkus’ post today, and am struggling to figure out what makes it “must read” material. I would have been compelled if I’d seen reference to actual examples of the problems he discusses. I would have been further compelled if it didn’t begin by assuming a very narrow definition of what constitutes policy relevance. And finally, I’d be more compelled if there were some evidence that political scientists don’t understand the dynamics he is addressing. Who are the naive simpletons he’s characterizing here?

Then again, I am a think tanker, so maybe I’m part of the problem and this post is a red herring, intended to get you all to keep cranking out the policy relevant stuff.