Yesterday the picture of little Alan (previously identified as Aylan), lying dead in the sand on the shores of the Mediterranean, circled the world. It provoked strong reactions from those who ‘witnessed’ his death in this manner and, not unlike the debates following some of the images shared after 9/11 (I wrote about that then), people questioned the ethics of sharing the images particularly without warning (see replies by some who shared here, here & here and note that his father wants the image to be shared if it can provoke action).

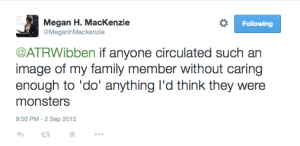

Indeed, it was this tweet  from fellow Duck Megan MacKenzie that prompted today’s post (you can read our full exchange here). Her concerns are echoed, and expanded, in this piece (which also links to issues I discuss in a previous post on the #BBOG campaign). Of course there are things that we can do, even from the comfort of our own homes: We can sign petitions, such as this one from Avaaz or this one to force a debate in the UK parliament. We can share lists of things to do such as this one – and maybe get involved locally in Greece, Germany, or Italy (no matter where you are you can get involved locally – there are needs in San Francisco, where I am, and Sydney, where Megan is. If you have information for your local area, feel free to share them in the comments).

from fellow Duck Megan MacKenzie that prompted today’s post (you can read our full exchange here). Her concerns are echoed, and expanded, in this piece (which also links to issues I discuss in a previous post on the #BBOG campaign). Of course there are things that we can do, even from the comfort of our own homes: We can sign petitions, such as this one from Avaaz or this one to force a debate in the UK parliament. We can share lists of things to do such as this one – and maybe get involved locally in Greece, Germany, or Italy (no matter where you are you can get involved locally – there are needs in San Francisco, where I am, and Sydney, where Megan is. If you have information for your local area, feel free to share them in the comments).

But …

… I would argue that, as scholars, we can and must do more.

What if we made a commitment to tell the story of Alan, his brother Gilan [correction: his name is Ghalib/ Galip in Kurdish], and mother Rehan who all drowned and his father Abdullah Kurdi who now has to go on without them (and who wants his tragedy to spur action)?  What if we used our knowledge of global affairs to connect the dots and lay bare how Alan’s story is also the story of the global community’s failure to successfully address the conflict in Syria? A story that also highlights anti-immigrant policies adopted by Canada (Alan’s aunt had been doing all she could to support his family and get them to Canada), a settler-colonial state that neglects its indigenous population? Alan’s death is also a consequence of U.S. foreign policy, first in destabilizing the region starting with the invasion of Iraq and incubating ISIS, and more recently supporting (albeit inconsistently) Turkish ambitions to prevent any Kurdish independence exemplified in the fight in Kobane, Alan’s hometown. His is a death that might have been prevented had there been some pathway to safety other than a dinghy. Let us remember, what it means to be a refugee (and how problematic it is to speak only in terms of migration, though that also quickly gets complicated [EDIT: see this great post on TDOT also that goes into some of the more technical details] ). As Warsan Shire exclaims, “you have to understand that no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land” (click here to hear the full poem, really, do it!).

What if we used our knowledge of global affairs to connect the dots and lay bare how Alan’s story is also the story of the global community’s failure to successfully address the conflict in Syria? A story that also highlights anti-immigrant policies adopted by Canada (Alan’s aunt had been doing all she could to support his family and get them to Canada), a settler-colonial state that neglects its indigenous population? Alan’s death is also a consequence of U.S. foreign policy, first in destabilizing the region starting with the invasion of Iraq and incubating ISIS, and more recently supporting (albeit inconsistently) Turkish ambitions to prevent any Kurdish independence exemplified in the fight in Kobane, Alan’s hometown. His is a death that might have been prevented had there been some pathway to safety other than a dinghy. Let us remember, what it means to be a refugee (and how problematic it is to speak only in terms of migration, though that also quickly gets complicated [EDIT: see this great post on TDOT also that goes into some of the more technical details] ). As Warsan Shire exclaims, “you have to understand that no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land” (click here to hear the full poem, really, do it!).

So, maybe there is ‘something’ that we can do indeed – let us tell the stories of all the children who died crossing the Mediterranean – and their parents, and grandparents, and aunts, and uncles. Let us use our knowledge of global politics to find out who they were and carefully disentangle how our policies influenced their journeys. Let those stories inspire us to offer a helping hand – but also to identify points of resistance and demand policy changes.

Stories Matter.

Many stories matter.

Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign,

But stories can also be used to empower and to humanize.

Stories can break the dignity of a people,

But stories can also repair that broken dignity.

(Chimamanda Adichie)

Annick T.R. Wibben is an Associate Professor at the University of San Francisco. Her research straddles critical & feminist security studies, international theory, and (feminist) international relations. She also has a keen interest in methodology, representation, and narrative.

Annick, thank you for this thoughtful post. I know it was a difficult choice to post a photo of Alan given the controversy about images. But it does seem that the images themselves have a powerful role to play in galvanizing the kind of change both you and Megan rightly insist we must focus on – non-superficial change, real, critical thinking about the kind of global society we live in.

People simply don’t respond to numbers. I am inclined to circulate these images as well at the father’s request, despite – indeed because of – the strong emotions I feel when I see them and think of my own son. Until this happened, I had not realized that Facebook has in fact been censoring pictures of many other drowned children on European beaches. It has made me wonder whether Alan would be alive today if we had been allowed – forced, I suppose, given our natural desire to want to be shielded from this – to acknowledge the deaths of those earlier victims.

https://usuncut.com/world/facebook-banned-photos-europes-refugee-crisis/

Thanks, Charli. I did indeed have several iterations of this post drafted… with and without the picture. I normally don’t share images/ videos of violence, precisely because I worry about the ethics of doings so. I ended up posting it because Alan’s father (see links in the post itself), asked us to.

The little boy’s name (the brother of Alan) is not Gilan. It is Ghalib. Or in the Kurdish spelling, Galip.

Thanks for the correction! I’ll make a note above…

Let me share another status by a fellow academic on the issue: “FEW NOTES ON THE RECENT REFUGEE TRAGEDY

When it comes to lecturing Turkey on human rights issues, the EU officials are so enthusiastic about it. However we should also see the gap between rhetoric and action. Because our actions are our real tests.

Sealing off the borders in the face of humanitarian crises only shows how much Europeans really care about real human tragedies. Today, Turkey, with an economy of $800 million GDP, is hosting over 2 million Syrian refugees, while the EU with an $18 trillion economy feels uneasy about the economic burden that might be caused by the refugee flow.

Note: Also remember that the EU signed “Readmission Agreement” in 2013 with Turkey to send all illegal migrants/refugees, who came to EU over the Turkish route, back to Turkey. I guess they say: “you deal with it, we only criticise!” Haluk Ozdemir

Evren – You are absolutely right to point this out. Can Mutlu has written a great post over at TDOT (which I added a link to above) that explains in great detail also the status of Syrian refugees in Turkey, the issue of readmission agreements, etc.

A blog post can only ever cover so much, but if you follow the embedded links above a lot more detail emerges… at least that’s the hope!

Thanks for your post, Annick. I have two things to add.

The first relates to the way in which academics are assessed–for hire, for tenure, for performance, and for promotion. Outputs and activities for public audiences are seldom assessed favourably in these exercises. The stigma of academic blogging–and in IR in particular–is a related and more widely-known danger of public engagement that is variously felt in different workplaces and countries. What needs to change is the attitudes and mechanisms at the institutional-level which dissuade or penalise these outputs. For this, senior academics, by which I mean those afforded tenure, must take the lead on protesting on their colleagues behalf. Too often it has been untenured faculty that have raised the issue of being personally and professionally penalised for engaging the public after receiving, in many instances, public monies.

The second point I’d like to add is about “expertise” and passion. I believe academics must not merely look to impart their supposed expertise on others–in media, in articles and blogs, in epistemic communities, etc.–but also allow themselves to follow and display their passions for the causes that they have have research interest or not. I know first-hand what it is like to become disenchanted with the production of opinion and blogs, but I believe it is not as though those outputs–much like those your advocate–are of no importance or value, but rather that they must not be quarantined as expertise removed from our passions.