The Russian Federation covers more territory than any other country. It has a large nuclear arsenal, skilled weapons designers, and the world’s fourth largest military budget—after the United States, China, and Saudi Arabia. But it maintains that budget—which comes it at roughly 12% of US military expenditures—by spending a larger percentage of its GDP on defense than does the United States, China, Britain, France, Japan, or Germany. Indeed, if the major European economies boosted defense spending to 3% of GDP—still short of Russia—they would each have larger military budgets.

Of course, military spending is a poor proxy for capabilities. Russia has a larger population than any other European state, along with a big army, extensive air-defense network, and other indicators of martial prowess. But it also has a smaller economy than the state of California, and still cannot indigenously produce much of the high-tech accruement of modern warfare. Moscow can certainly overwhelm many of its neighbors, but it isn’t a political-military juggernaut.

I consider such remarks necessary in light of the current freakout over Moscow’s intervention in Syria, including here at the Duck of Minerva.

Thankfully, a wave of cooler heads have started to push back against the hyperventilations of #resolvefairy acolytes. But the whole notion that Putin is a master strategist, and that whatever goes down in Syria is a result of his outmaneuvering the West in Ukraine, needs a reality check.

Let’s review.

- In the summer of 2013, Ukraine’s incumbent party—the Party of Regions, under President Yanukovych—played its traditional balancing act but was, when compared to its main opposition, relatively pro-Moscow.

- Putin initiated a trade war against Ukraine to force it out of its European Union Association Agreement. It worked.

- Except that it caused a backlash that brought down the government in a (largely) non-violent revolution. The new regime was decidedly less pro-Moscow and more pro-western.

- Moscow responded, at first, by seizing control of Crimea—an asset from the perspective of Russian nationalism but an economic liability—and its aging naval fleet. In doing so, it violated its obligations under the Budapest memorandum and produced widespread concern among the major European powers.

- Not content to stop there, Russia initiated a proxy (and not-so proxy) war in Ukraine.

- This war shows no signs of toppling a the Ukrainian government, and the ‘best’ outcome looks likely to be frozen conflicts by which Moscow might enjoy some additional leverage over a very unhappy Ukrainian government.

- Meanwhile, western sanctions have compounded the sharp drop in petroleum prices to send Russia into an economic contraction.

- Russia signed a pretty unfavorable deals with China.

- Sweden and Finland are contemplating NATO membership.

- The US has more capabilities deployed directly on the Russian border than, well, ever.

- It is difficult to really demonstrate that the United States is in any way less secure since the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict.

Yes, Putin’s actions have been very bad for people living in Ukraine—and for Russian soldiers deployed there. And we’re not looking at Bush-sized strategic blunders. But you have to set a very low bar in order to see these developments as some kind of magnificent victory for Moscow.

In essence, you have to think that the United States only ‘wins’ when it gets pretty much every outcome that it prefers. In the complex and capricious arena of international politics, that’s rather unrealistic. Indeed, it’s a dangerous way to approach foreign policy.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Spot on. I think the gap between perceptions and reality is also a key reason for why Putin has embarked on this strategy at the international level: the myth of Putin as the heroic figure who stemmed the Western advance and restored Russia to greatness is what compelled him to escalate the conflict in Ukraine further and further, because backing down would’ve undercut his domestic legitimacy even when it would’ve been smarter from a national interest perspective. Though he appears not so much concerned about future credibility rather than his personal power.

I have seen this argument made in a number of places and it misses one very important point: Purchasing Power Parity in defence. For example, an Su-34 (currently active over Syria) reportedly costs about $37 million as of 2014. Further, virtually of it is sourced from within the Russian federation so it is insulated from currency movements. On that basis Russia can buy three Su-34s for every F-35, Typhoon or Rafale the European country purchases. Now apply the same thing across the Russian defence industry and consider the pay differential.

This goes a long way to explaining why Russia is able to maintain a much larger force structure than any European country currently does and with a very balanced set of defence capabilities.

I’m not sure about the figures, but I suspect that you’re right. The comparisons I draw are crude—but they should drive home a basic point: the underlying balance of mobilization potential is much less favorable to the Russians, even without throwing the US into the mix. Most of the barriers in Germany, France, and the UK are political.

And don’t forget that Russia’s military-industrial complex lags in indigenous production of defense electronics and other key aspects of contemporary warfare; there’s a reason why they were buying key components—and even systems—from Europe.

If Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) counts for defense spending than it also counts for other forms of spending. This is why the insistence that Russia’s economy is smaller than California’s, or worse yet Italy’s, are basically absurd. How much of California’s ‘GDP’ is basically paper assets such as the bloated value of Apple stock, vs. Russian hard assets in the ground and the world’s largest country? How about Russia’s population being three times that of California and 1.8 times that of Italy factoring into the equation?

I’ve seen reliable figures that place Russian per capita GDP (but one would say per capita is overweighted by Moscow having until recently more billionaire oligarchs than any city) at a respectable 27,000 per year, or better than several ex-Warsaw Pact NATO states and not too far behind ex-Soviet state Lithuania and fair-sized Slavic neighbor Poland. I’ve also seen some cynics suggest if oil prices rise by as little as $7-$10 per barrel as the result of the Syria turmoil the dollar cost of Russia’s bombing campaign and associated base security pays for itself, though that may be an overestimate. The Saudis are maintaining production flat out as are the Russians but both sides have reserves and unlike Saudi Arabia Russia has things to export, like grain and weapons, other than hydrocarbons and imams. Even if one believes the Saudis drove down the oil price to hurt Russia and get them to reconsider their rock solid and deepening support for Assad or his chosen successor, the Kingdom’s resources are not unlimited. The Saudis are also finding out that while US TOWs can kill Syrian Arab Army (SAA) soldiers in Syria Saudi soldiers can die on Saudi soil from old Soviet ATGMs in Iran’s arsenal in the hands of Houthis and Yemeni tribesmen. Although some here may see Saudis dying while KSA tries to bleed Syria by proxy is a feature and not a bug, the Saudis are corrupt but not stupid. They are not going to keep bleeding and dying indefinitely or even experience brazen Houthi attacks deep inside the Kingdom just to satisfy U.S. neocons or neoliberals desperate to turn Syria into a second Afghanistan now that Putin didn’t take the bait in Ukraine.

Incidentally, the general public may be dumbed down and barely paying attention, but thanks to the Internet people do notice when we have glossy full color photographs of Russian jets on the tarmac in Syria and crappy, below Google Earth grade black and white shots of what look like combine harvesters as ‘proof’ #RussiaInvadedUkraine. Ditto for the fanatical refusal of the U.S. to release any satellite pics of a Russian BUK in eastern Ukraine before or after MH17 was shot down. I would have thought they could’ve at least released some slightly modified versions to protect those holy sources and methods, but no, we have to trust that some guy sitting in England in his underwear using photos helpfully supplied by the Ukrainian SBU (the same SBU that said the separatists were planning to build a dirty bomb in their basements) for America’s MH17 proof. And we wonder why Putin is seen as the good guy or at least the chessplayer who’s outfoxed America at every turn? When will our policy stop being so stupid and our propaganda start making sense? Al-Nusra front last I checked was designated by the State Dept. as a terrorist group and all this whining about how ISIS is 100 kms away doesn’t change the fact that Al-Nusra swore allegiance to Al-Qaeda and they’re arm and arm one building over from ‘our’ CIA trained or TOW armed jihadists.

One last thought: if Sens. McCain and Cotton got their wish, and the U.S. shipped Stinger missiles to the ‘Free Syrian Army’ tomorrow, do we get to charge them with material support of terrorism if those MANPADs are surrendered by FSA to Al-Nusra or ISIS? Asking for a friend here. How about civil lawsuits naming McCain and Cotton as defendants along with the government sponsors of Al-Nusra namely Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey if one of those Stingers gets used to shoot down a civil airliner? Have the fanatical neocons and neoliberals really thought through seeing the Stingers captured by Spetsnaz or CIA-supplied satellite maps of Russian bases pulled off dead Al-Nusras on RT is going to mean to American credibility in the ‘war on terror’? The age of just putting out CIA/DoD talking points on CNN or Fox News and not having to cope with the other side’s information warfare are over, people.

You do realize that the figures I provided are in PPP? As the caption says, “GDP (PPP) for….” As are the numbers that put Russian GDP at (slightly) less than California’s.

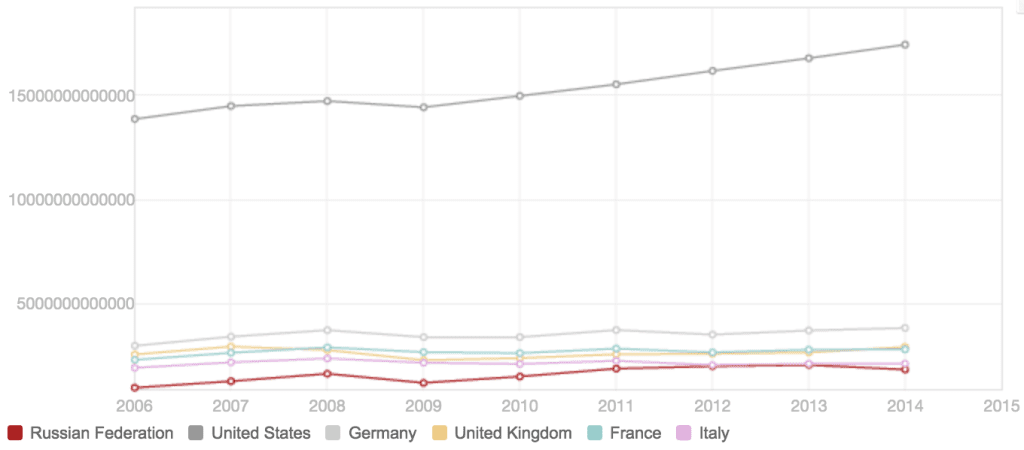

Here’s GDP per capita (PPP) through 2014. I’d say the most salient “one of these is not like the other” comparison involves the relative lack of hydrocarbon exports.

1) As I said, California’s GDP is bloated by paper assets. And there’s plenty of poor people living in that drought plagued state to adjust the PPP figures downward compared to all the millionaires and billionaires.

2-3) Russia is also one of the world’s largest grain exporters.

4) You find my comments ‘difficult to follow’ because:

Like basically the entire U.S. Establishment you’re in denial that the Kiev regime the U.S. established is economically failing, wildly unpopular, and lying about 14 to 16,000 KIA as opposed to the figures the State Dept. funded rag Kyiv Post puts out of a mere 2,300 ‘geroim’ who died in a losing campaign in Donbass. And that Russia can outlast it and make Washington own every failure of the Ukrainian State, including its human rights abuses, indiscriminate shelling, irredentist ideology which isn’t all that popular in Poland (go look up ‘UPA’ and ‘Volyn’) or the rest of Europe outside of the fanatical Russophobe set.

Reality — namely when the rest of the world starts dropping the dollar and we can no longer print as much money as we like to fund our bloated military industrial complex and bribing much of the planet including Ukrainians to do our bidding — is going to hit hard. Have a nice day and thanks for noticing the U.S. IP instead of slinging the usual bulls–t that a native English speaker is a Kremlin troll (and that the ‘Kremlin trolls’ all amazingly learned or got Yandex translate to make them appear fluent in Spanish, German, and Italian — US Ukraine policy is not nearly as popular as you think).

You can also get a sense of the actual diversification of Russian exports here: https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/rus/

Like most commodity-driven rentier states, the Russian government really squandered opportunities to diversify its economy. Which is very much a shame. Russia has significant human capital.

Let’s not mention the tiny country in the Mediterranean with a lot of Russian-speakers that might’ve (cough cough) helped Moscow catch up in terms of defense electronics and UAVs.

Great post Dan

A few other points:

Not content to stop there, Russia initiated a proxy (and not-so proxy) war in Ukraine.

And Russia’s proxies kicked the living crap out of our proxies, such that they ended up driving around in Humvees and showing off those super duper mortar detection systems still wrapped in the original plastic.

This war shows no signs of toppling a the Ukrainian government, and the ‘best’ outcome looks likely to be frozen conflicts by which Moscow might enjoy some additional leverage over a very unhappy Ukrainian government.

Having seen its trade with Russia collapse and having no real demand for its products other than warm bodies, toilet cleaners and a handful of specialists in the EU already swamped with migrants fleeing conflicts in the greater Middle East, the Ukrainian government will be surviving on International Monetary Fund loans which can never be repaid courtesy of the American and EU (German) taxpayer for the indefinite future.

Meanwhile, western sanctions have compounded the sharp drop in petroleum prices to send Russia into an economic contraction.

Severe recession yes, depression no. And Russia’s economy was slowing down due to the recession of its European trade partners and China’s slowdown before the Ukraine crisis.

Russia signed a pretty unfavorable deals with China.

Unfavorable according to whom?

Sweden and Finland are contemplating NATO membership.

Only because the U.S. is subsidizing the likes of Carl Bildt, and by the way don’t you think Swedish and Finnish voters are going to soon start to notice that NATO is pretty damned useless at keeping out hordes of military age males from the Middle East while it’s hyping the awesome Russian threat? I also seem to recall Sweden surviving the first Cold War when the USSR had vastly more men under arms than modern Russia and could’ve occupied Stockholm in a day without having to join NATO. Is this really about the Arctic or something, or just the Swedish arms industry being in bad shape?

The US has more capabilities deployed directly on the Russian border than, well, ever.

Which inversely means that American troops are in far more geographically and numerically inferior position than they ever were during Cold War 1.0 sitting on the Fulda Gap hundreds of miles from the Soviet Union proper backed by 12 Bundeswehr tank divisions. Today not only the RAND Corporation but numerous analysts have admitted the Russians could occupy the Baltics in 72 hours — if they had any reason to. And their S-400s in Kaliningrad can basically shut down the eastern Baltic air space for 150 mile radius. Did I mention they have GLONASS to within 10m guided hypersonic Iskanders we can’t shoot down that can destroy every significant NATO installation within 300 miles being deployed to their western exclave?

It is difficult to really demonstrate that the United States is in any way less secure since the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict.

If you don’t count the lost U.S. credibility and the sense that Washington was ready and eager to fight Russia to the last Ukrainian, no.

Yes, Putin’s actions have been very bad for people living in Ukraine—and for Russian soldiers deployed there.

https://thesaker.is/seeing-through-the-doublethink-primary-evidence-on-losses-of-the-combatants-at-donbass/

Estimated Ukrainian losses based on LostArmor figures

It’s been far worse for the Ukrainian Army which has, contrary to the bullshit put out by the Kyiv Post and the bravado about killing bazillions of VDV spetsnaz, has lost between 13 and 15,000 KIA and probably double irreplacable losses in terms of wounded, to about 5,500-7,000 ‘combined Russian separatist forces’ of which the vast majority were Ukrainian passport holders before the war. The Pentagon is bullshitting Ukrainian casualties to prop up sagging morale, but the mobilization is called ‘mogila (grave) ization’ among many young Ukrainians who prefer to flee to Poland, Romania or even Russia than die in Donbass while Poroshenko’s chocolate company still owns Russian assets (some real ‘war’). Did we mention if #RussiaInvadedUkraine for real and Putin really was hellbent on overthrowing the government in Kiev or at least marching to the Dnieper we’d see Su34 gunsight footage of Ukrainian targets getting lit up like we’ve seen from Syria in the last week?

Sorry to burst your bubble but Moscow’s proxies kicked our proxies’ asses. The only reason they didn’t take Mariupol or push to the pre-war borders of the Donetsk and Lugansk regions is because it suits Russia’s interests to freeze the conflict and make the U.S. pay for the rest of Ukraine until we or more likely our European allies (Germany cough cough) get tired of the sanctions and subsidizing the corrupt and failing government in Kiev.

I should also say in fairness here that Russian media saying Ukrainian per capita GDP is now below Moldova or Albania’s (aka the poorest countries in Europe) and Ukrainian retirees pensions are less than Bangledeshis’ get rely on the same dollar terms fallacy that shrinks Russia’s economy down to Italian sizes, when in PPP terms Russia is probably in 7th place ahead of Italy but comfortably behind Germany and India’s economies in size. Ukrainians may be getting poorer but Kiev certainly isn’t as poor as Chisinau, Tirana or Daka by a long shot.

Largely non-violent? Even before a single ‘little green man’ deployed from Russia’s bases on the Crimea many Berkut riot policeman, mostly hailing from the most pro-Russian parts of the country, were dead on the Maidan. Ukraine’s civil war didn’t start when pro-Russian rebels took over government buildings, put up flags and declared themselves independent of the central government. That would have been when pro-Maidan demonstrators — as well as armed Right Sector thugs — took over government buildings and looting arsenals in Lvov. Sorry but Western MSM memories are selective and short. Meanwhile the ‘pro-Yanukovych’ or even ‘Russian’ snipers on the Maidan all got away like OJ’s real killers, even after shooting from buildings controlled by the ‘Maidan Self Defense’ who were armed with pistols, shotguns, hunting rifles and Molotov cocktails. Who was directing the ‘Maidan Self Defense’? Andre Parubiy, who played a key role in the new government. Sorry but the forensic evidence is overwhelming as were the rumors picked up in the leaked phone call from Ashdown to the Estonian envoy that people associated with the new U.S.-backed regime shot their own Maidan activists in an ultra-cynical move to finally overthrow Yanukovych, who was already on his way out in elections due within 4 months.

https://www.academia.edu/8776021/The_Snipers_Massacre_on_the_Maidan_in_Ukraine

MSM also ignored the vicious ultra-nationalist attack on a busload of anti-Maidan activists near Crimea that killed several people and left many others severely injured. Just as they downplayed the Odessa massacre which played a key role in radicalizing a lot of people to the Novorossiya cause and in seeking vengeance on the battlefield against the Right Sector group that shot, stabbed, beat or burned to death 50+ people in the Trades Union Building in a pro-Kiev progrom. After all, having groups murdering their political opponents in the name of a united Ukraine, and labeling the dead ‘separatists’ or ‘Russian provocateurs’ when they were all citizens of Ukraine is much more convenient than acknowledging Kiev hasn’t brought a single perp in the mass killing to trial, and the U.S. State Dept. is utterly and shamefully silent on this. As they are about Kiev’s blockade of the Donbass hardly doing much to win ‘hearts and minds’ or its massively indiscriminate shelling and GRAD rocketing of heavily populated towns and cities. When the Serbs or Assad did it, it was a war crime. When Ukrainians do it it’s because the evil separatists are all shooting their own people to make the heroic Ukrainian army look bad or because the separatists shoot from school and hospital yards (not exactly true, and the Ukrainians also position their equipment close to such).

‘Violent insurrection for ME greater Galicia/Ukrainian patriot but not for thee pro-Russian vatnik’ was never going to be a recipe for a stable post-Maidan Ukraine where people would simply lay down and accept the legitimacy of a regime overwhelmingly backed by the West and people from western or central parts of Ukraine whose first (widely acknowledged even by Maidan supporters as stupid) act was to revoke a law that had formally established Russian as a legal language equal to Ukrainian in the courts (not on the streets, since the majority of even the most fanatical Ukrainian nationalists mostly communicate in Russian and the ineptitude of politicians like Klitschko with Ukrainian grammar is a running joke).

That’s just one of many problems with this piece, which while it commendably tells people to chill out and not start WW3 by shooting down Russian planes bombing Al-Nusra front, still speaks from a position of arrogance and a certain misinformed state on Russia’s strengths — and weaknesses.

By any standard, the toppling of the Yanukovych regime was reasonably non-violent. If you think otherwise, than you don’t know much about the level of violence found in typical revolutions.

I’m not interested in engaging with the rest. There are plenty of places that you can go to argue conspiracy theories about events in Ukraine, as well as the role of various foreign and domestic actors. But in the context of this discussion, your posts are the equivalent of spam.

This is why discussion is increasingly impossible. Any dissent from the U.S. party line is labeled ‘conspiracy theorizing’ or ‘Kremlin troll’ ing. Even when George Friedman the CEO of the ‘shadow CIA’ Stratfor who should know tells Kommersant (a previously WSJ owned, liberal leaning pro-Western Russian newspaper). Take some responsibility — the U.S. sure as hell had plenty to do with Yanukovych’s violent overthrow no matter how much window dressing was put around the trebuchets and killing of riot policemen (such violence labeled “revolution” by us is aka “terrorism” “anarchists” in states backed by Washington).

As we said you cannot be a western or centralUkrainian nationalist, kill a bunch of Berkut riot policemen hailing mostly from Crimea and eastern Ukraine, and then act ‘shocked’ when those regions chose to revolt with a little bit of help from the Kremlin.

The United States instantly endorsed violent regime change in Ukraine and then set about trying to help the new, unconstitutional (they instantly sacked several of the Yanuk appointed judges), unelected and installed by force regime attack those in Donbass who violently resisted it along the same lines as Maidan. The only distinction is that the Donbass rebels had slightly more firepower than the greater Galician nationalists backed by the U.S. who looted police station arsenals in Lvov.

https://mikenormaneconomics.blogspot.com/2015/01/stratfor-chiefs-most-blatant-coup-in.html

You’re entitled to your own opinions, you are not entitled to your own ‘U.S. didn’t do nuthin’ ‘facts’ regarding the Kiev government’s members having murdered or at least been complicit in covering up the murders of pro-Maidan activists by snipers who all easily got away despite being surrounded by armed Maidan self defense activists who stood down that day. Or that the Kiev government chose to shell and bomb cities rather than negotiate for autonomy or simply ignore the armed activists who’d taken over government buildings and put up barricades around them JUST LIKE THE UKRAINIAN NATIONALISTS DID IN LVOV.

And once again, the conflation of ‘moderate’ ‘Free Syrian Army’ franchisees with Al-Qaeda sworn allegiance to Al-Nusra front jihadists who they literally share office space with will bite U.S. policy and the mainstream media in the ass in Syria. Count on it.

“Most blatant coup in history” – George Friedman CEO of Stratfor on the overthrow of Yanukovych

https://russia-insider.com/en/2015/01/20/2561

Sorry, but you are wrong, wrong, wrong. I was in Kyiv for part of the Maidan protests. I spoke to countless protestors. I also have a long history of following Ukraine, going back decades with an advanced degree related to Ukraine.

The protests were funded, initially, by Ukrainian oligarchs. Not the U.S. The reason had little to do with corruption, or the EU, or as an anti Russian movement. It had to do with splitting the pie. Many protesters, on both sides, were paid to be there.

However, the protests soon grew to include those sick of Ukrainian corruption. I heard this repeatedly in chats with Ukrainians before Maidan, from those who never appeared on Maidan, and who lived all over Ukraine. They were tired of the corruption and indignity related thereto that they lived with daily. The U.S. was reacting to events on the ground. They didn’t create them.

There is little doubt the Yanukovych regime started shooting at protesters in an attempt to clear Maidan. Were there attacks on police from the other side? Definitely. But the shootings by the police is what lead to Yanukovych losing Rada support.

To suggest that this was a coup directed by the U.S. is folly. Ukraine is not particularly important to the U.S., and had America wanted to put Ukraine in its camp, it could have done so at any time since the collapse of the USSR quite easily, including, even, under a Yanukovych presidency. The reality is, Ukraine is not that important to American geostrategic interests.

If the protests were funded by oligarchs and the protestors paid to be there, it can hardly be said to be a grass roots movement, can it?