Yesterday, Russia became the fourth country in recent weeks to announce its intent to withdraw from the Rome Statute and the International Criminal Court. In doing so, it joins South Africa, Burundi, and Gambia in expressing concern about the institution’s functionality and legitimacy as an international institution. The Philippines is also reportedly contemplating departure.

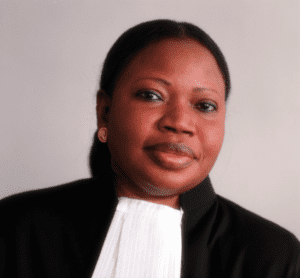

Because Russia never actually ratified the Rome Statute, its act of “departure” is–as many have pointed out–largely symbolic. Yet it also comes with a stinging rebuke from the government of Vladimir Putin, which declared that the institution “has not justified the hopes attached to it” and has failed to establish itself as a “genuinely independent, authoritative organ of international justice.” Coming from a government that has itself been the subject of a war crimes investigation (for atrocities committed in South Ossetia in 2008), it may seem easy to write off Russia’s criticisms as sour grapes. Others who have left the institution have self-interested motives, too. Burundi, the first country to leave the court, was also the subject of a preliminary investigation based on political killings. South Africa became the target of criticism after its failure to apprehend and surrender indicted Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir. Gambia, the home country of prosecutor Fatou Bensouda–a former justice minister, accused the court of the “persecution and humiliation of people of colour, especially Africans.”

The criticism of the ICC’s focus on Africa is a long-standing one, and it is not entirely without merit. A look at the ICC’s investigations bears that out. However, it is curious that this reached a breaking point precisely during a year in which the ICC was opening investigations and preliminary investigations elsewhere in the world, in places like Georgia and Afghanistan. The criticism of the court as a racially biased organization is likewise curious since the court’s top four positions are all currently held by women of color. In addition to Bensouda, the court’s presidency is overseen by President Silvia Fernández de Gurmendi of Argentina and Vice-Presidents Joyce Aluoch of Kenya and Kuniko Ozaki of Japan.

With this in mind, it is entirely appropriate to ask: Is the current “legitimacy” crisis in the ICC really about wasteful spending, inefficiency, and racial bias, or is it also–at least in part–about certain states’ resistance to being held accountable to an organization where the four most influential posts are held by women? At the time of Judge Fernández de Gurmendi’s election last year, the IntLawGrrls blog heralded the historic moment and noted that by having a female leader, the ICC joined a tradition that included the leadership of women in ad hoc war crimes tribunals and in the International Court of Justice. Yet 2016 has already shown us the extent to which women face backlash and resistance in the political sphere. The failure of the UN to elect a woman to the position of Secretary-General, despite unprecedented public pressure, illustrates that the highest levels of international governance remain a boys’ club. The sidelining of women’s voices to an advisory board in the Syrian peace talks and the initial failure of the gender- and sexuality-inclusive peace agreement in Colombia further underscore this dynamic. Ultimately, an African, female prosecutor who proactively pursues mostly male offenders and who highlights acts of gender-based violence is likely perceived by many in the international community as a transgressive figure. An entire international organization led by women, more so. Where the ICC goes from here remains unclear, but it is highly likely that any comprehensive reform will come at the cost of women’s voices, whether that is the intent or not.

Dr. Alexis Henshaw is the author of Why Women Rebel: Understanding Women’s Participation in Armed Rebel Groups (Routledge, 2017) and co-author of Insurgent Women: Female Combatants in Civil Wars (Georgetown University Press, 2019). She is currently an assistant professor at Troy University.

Her research interests include gender issues in international politics, civil wars, conflict management, and Latin America. She has also published work on research methods and design, including pieces focused on pedagogy, data analysis & visualization, and inclusivity. Her work has appeared in Journal of Global Security Studies, International Feminist Journal of Politics, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Small Wars & Insurgencies, and a variety of other peer-reviewed outlets.

Dr. Henshaw has written for The Conversation, Duck of Minerva, Political Violence @ a Glance, and The Monkey Cage, the political blog of The Washington Post. She has authored reports for the U.S. Army's Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute and the Centre for Women, Peace, and Security at the London School of Economics. She is an associate fellow with the Global Network on Extremism and Technology and has consulted with UN Women, the UN Counterterrorism Executive Directorate, and a variety of other organizations. Dr. Henshaw received her Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Arizona with a certificate in Gender and Women’s Studies and previously taught at Duke University, Miami University, Bucknell University, and Sweet Briar College.

0 Comments