This Bridging the Gap post is by BTG co-director Naazneen H. Barma, who also serves as Associate Professor of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School.

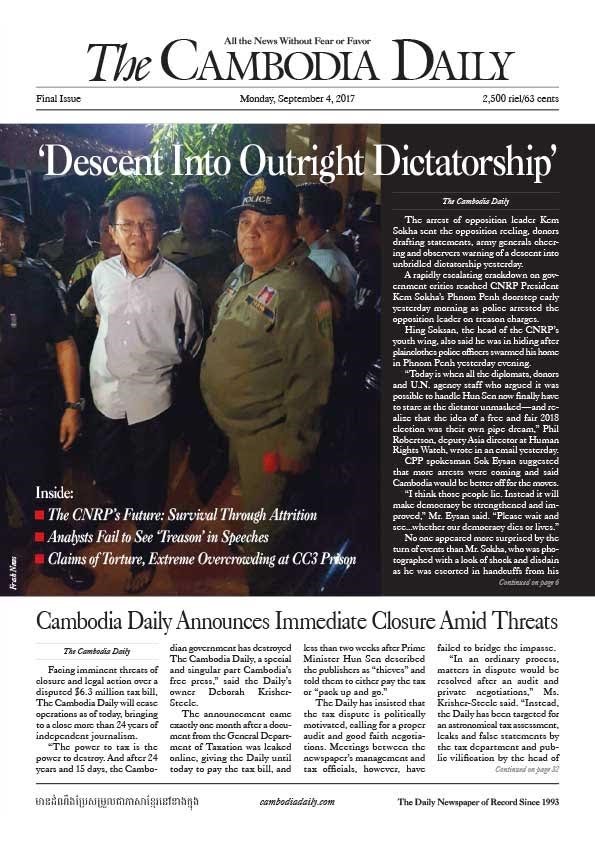

Hun Sen, the longtime leader of Cambodia, has used almost every tool in the authoritarian playbook to consolidate his grip on power over the past three decades. Things came to a head early this month when one of Cambodia’s two premier English-language newspapers, The Cambodia Daily, was forced closed after being blindsided by the government with a $6 billion tax bill that it couldn’t possibly pay. Rendering an extraordinary confluence of dictatorial strategies, the newspaper’s final issue on September 4, 2017, headlined with the news of the midnight arrest of the leader of the country’s only real opposition party.

The Cambodia Daily, although a relatively young newspaper—started in 1993 under the civil society opening facilitated by the United Nations—turns out to have been the training ground for a number of prominent commentators on the political scene in Southeast Asia and beyond. Moving tributes to the paper and its tenacious role in Cambodia’s nascent and now troubled democracy have poured in. Julia Wallace captured beautifully how the newspaper’s aspirations and fate have mirrored those of the country’s politics.

The Cambodia Daily’s final issue fronted, as pictured above, with Kem Sokha, head of the Cambodia National Rescue Party, being led away from his home in handcuffs on charges of treason. This was only the latest move in the inexorable escalation of Hun Sen’s actions against his political foes. One major opponent after another has been swatted away with bribery, violent intimidation, and threats of exile. A once vibrant civil society scene, if still in its infancy, has been dulled to wary unease with similar tactics. Civilian protests about issues ranging from unfair working conditions in the country’s sweatshops to corrupt land grabs lining elite pockets and displacing the poor have been clamped down upon as Hun Sen inveighs against “color revolutions.” The Voice of America and Radio Free Asia have been silenced in the country; and the U.S.-funded National Democratic Institute has been kicked out.

How did this happen in a nation that seemed one of the most promising harbingers of peace and liberal progress in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War? Sadly, the international community’s attempt at post-conflict peacebuilding in Cambodia is at least partly to blame. This observation is based on research I completed for my recent book, The Peacebuilding Puzzle: Political Order in Post-Conflict States, and it holds across the three countries in the book’s comparative analysis: Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan. I find that the UN’s guided process of institutional engineering to achieve simultaneous state-building and democratization becomes captured by post-conflict elites, who co-opt interventions to achieve their own political objectives.

My analysis build upon James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen’s theory of institutional change, which emphasizes that political actors have available to them a repertoire of institutional conversion strategies: “insurrectionaries” actively mobilize against institutions; “subversive” actors bide time to achieve their goals by conforming in the short-run; “parasitic” actors exploit current institutions to achieve gain; and “opportunistic” actors rely upon institutional ambiguity to advance their goals. The winning elites in all three countries in my research have used all of these institutional change agent strategies in establishing a neopatrimonial political order in the aftermath of peacebuilding interventions.

Hun Sen, in particular, has given us a masterclass. On the heels of the peace settlement that ended its 25-year-long civil war, Cambodia became the site of one of the first multidimensional UN peace operations that was intended to be truly transformational in nature. The United Nations Transitional Administration in Cambodia—known as UNTAC—governed in partnership with the main Cambodian factions, relying especially upon the cooperation of the Vietnam-installed regime led by Hun Sen, and held the country’s first democratic election in May 1993. Surprising everyone, the royalists won a convincing plurality at the polls—but Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party dug in their heels immediately. Refusing to cede control over the state apparatus, Hun Sun negotiated a joint prime-ministership with Prince Norodom Ranariddh using tactics of blackmail and outright intimidation. The UN and the international community stood by while the party with the real control over the state—the CPP—governed the country single-handedly and both parties profited from parallel systems of patronage fueled by aid, natural resources, and the move to a market economy.

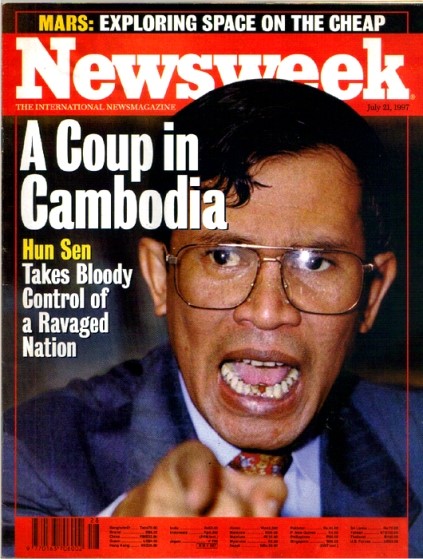

In June 1997, Hun Sen seized power outright in a violent coup against the opposition parties. Columbia political scientist Michael Doyle—who had worked in Cambodia as part of his secondment to the United Nations—had presciently warned of Cambodia’s “creeping coup” the year before. Under pressure from the international community, however, Hun Sen backed down. He invited Prince Ranariddh back to the country, acquiesced to new elections, and formed yet another power-sharing government.

I’ve visited Cambodia 5 or 6 times since 2000, either conducting field research or working on World Bank governance operations. My longest stint there was about 6 weeks in 2005 doing field research on UNTAC and its aftermath for my dissertation. That year I interviewed the now imprisoned Kem Sokha, then Director of the Cambodia Center for Human Rights. The civil society leaders I spoke with then were still cautiously optimistic that the civic space the UN operation had helped midwife was safe, leaving them able to play their essential role in cementing democracy in Cambodia. Political challengers were more cynical about their potential pathways to power through elections but the chilling effects of the 1997 coup had thawed and there was a renewed hope that Hun Sen would at least respect the basic democratic process and accommodate his political foes as a legitimate opposition.

The cycle of crackdown and reprieve has repeated itself three or four or five times since, moving in pace with electoral rhythms as the Cambodian People’s Party continues to find ways to win at the polls. Never resorting again to an outright coup, Hun Sen has demonstrated over the past two decades that more subtle power plays are perhaps even more effective. Sebastian Strangio has documented the playbook in his extraordinary Hun Sen’s Cambodia. He wrote in mid-September that the shuttering of The Cambodia Daily represent an unprecedented clampdown, even for Hun Sen, and notes that the latest moves come with a distancing from the United States and an ever-closer embrace with China.

Today, the political order in Cambodia is far from the rule-based, effective, and legitimate governance sought by the international community. It is firmly neopatrimonial, held in place by the distribution of patronage in exchange for political support, and paired with the ever-present specter of violence against political opposition. This state of affairs fits squarely with the findings in my book. The CPP-dominated Royal Government of Cambodia has cemented a system of resource generation and distribution for paying off rivals and supporters that is run in parallel to the formal trappings of government. The country’s most powerful elites have focused on developing predatory and exclusive control—what Global Witness called a “stranglehold”—over high-rent economic activity and, thus, political dominance. As these predatory patterns have increasingly permeated the country’s political economy, the role of violence and intimidation in influencing election results has given way toward other tactics of uncontested political dominance.

What could we possibly do to either nudge things in a better direction in Cambodia or improve the way we approach post-conflict peacebuilding? First and foremost, we have to recognize how post-conflict elites co-opt international interventions to build their own preferred version of political order. We must abandon the notion that post-conflict institutions can be designed and transplanted in whole cloth. Instead, our best bet lies in focusing on incremental governance improvements that align with the incentives of post-conflict leaders, while ensuring that the political space is expanded beyond these elites. (Somaliland’s autonomous statebuilding process offers a potential example, in contrast to international schemes in Somalia.) This becomes much harder to do when elites we have previously empowered move to shut down political space as aggressively as has Hun Sen.

Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way coined in 2002 the concept of competitive authoritarianism to describe hybrid political systems in which significant political contestation occurs but incumbents control and violate electoral rules so pervasively that the regimes are better classified as authoritarian than democratic—although they noted that these regimes could move in either direction. Marc Howard and Philip Roessler suggest, for example, that even in competitive authoritarian regimes there is evidence that experience with elections can result in “liberalizing electoral outcomes,” especially when opposition elites mount a strategically coordinated challenge to the incumbent. This looked like what was happening in Cambodia as recently as the July 2013 elections, when the Cambodian National Rescue Party fell just short of an enormous upset at the polls. Only four years later—as evidenced in the commune elections earlier this year, as well as Hun Sen’s latest moves—it seems that Cambodia’s trajectory has moved precipitously in the opposite direction.

My fear, based on this analysis and echoed it seems by most Cambodia commentators today, is that the darkness descending in Cambodia does not herald the dawn but portends a long, black night.

Bridging the Gap promotes scholarly contributions to public debate and decision making on global challenges and U.S. foreign policy. BtG equips professors and doctoral students with the skills they need to produce influential policy-relevant research and theoretically grounded policy work. They also spearhead cutting-edge research on problems of concrete importance to governments, think tanks, international institutions, non-governmental organizations, and global firms. Within the academy, BtG is driving changes in university culture and processes designed to incentivize public and policy engagement.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks