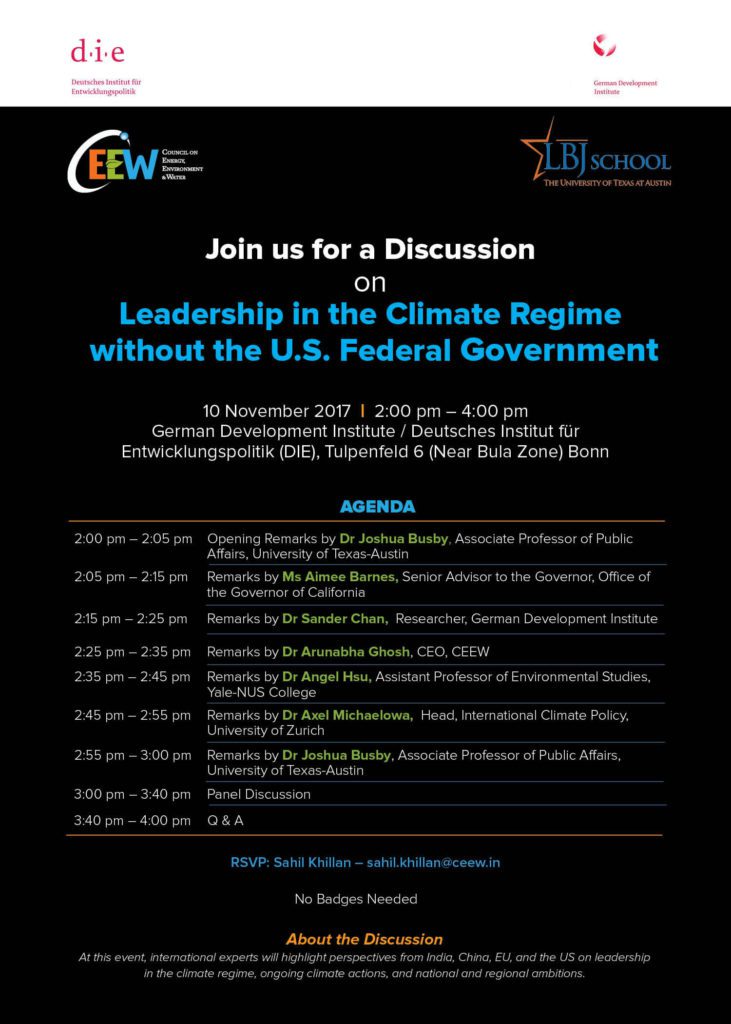

I am just back from the climate negotiations in Bonn where I organized a side event at the German Development Institute (DIE). The event was co-sponsored by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

These are my opening and closing remarks from the session. In subsequent days, I’ll post additional interventions from some of the other panelists. Panelists included Aimee Barnes, Senior Adviser to Governor Brown of California; Sander Chan of DIE; Arunabha Ghosh, CEO of CEEW, one of India’s leading think tanks on energy and climate; Angel Hsu, of Yale-NUS campus; and Axel Michaelowa of the University of Zurich.

Opening Remarks

I want to thank you all for coming today to this side event. I’m Josh Busby and an Associate Professor at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas. When Donald Trump was elected to be the 45th president of the United States, I knew that the climate regime was in for a difficult period after the heady optimism coming out of Paris in 2015.

I started a new research project, “Leadership in the Climate Regime without the US Federal Government.” When I heard about the DIE Interconnections side events, I thought this would be a tremendous opportunity to assemble some of the smartest professionals who work on this every day.

I thought it was important to get different perspectives on the role of different actors, not just folks knowledgeable about the actions of the world’s most important polities but also those of sub-national and non-state actors.

Today, we have a tremendous panel of speakers including Aimee Barnes, Senior Adviser to the Governor of California to talk about the remarkable steps the state of California is taking.

We also have Dr. Sander Chan of our host DIE who has done important work surveying the groundswell of non-state actor action around the world. We also are joined by Dr. Arunabha Ghosh, one of if not the leading strategic thinker in India on climate and energy. His Council on Energy, Environment and Water, which has done tremendous work analyzing the Indian landscape for action on energy and climate, has co-sponsored this event.

We also have Dr. Angel Hsu, of Yale-NUS in Singapore, who, among other research, has done important work understanding China’s evolving role at home and abroad on climate change.

Last but not least, we have Dr. Axel Michaelowa, who is one of Europe’s leading scholars on climate policy from the University of Zurich. He is also the lead author of the chapter on international agreements in the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

To leave ample time for questions, after some brief opening remarks, each of our speakers will speak for 10 minutes. I’ll give them a 1 minute warning before their time is up.

When Donald Trump was elected president of the United States last year, it was a crushing disappointment for many both in the United States and around the world who had hoped Barack Obama’s successor would offer continuity as the Paris agreement got off the ground.

Our collective fears were further confirmed when President Trump signaled in June his intent to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Under the rules of the agreement, the United States cannot officially withdraw until 4 years after the agreement entered into force, which is ironically the day after the next U.S. presidential election in 2020 as I understand it.

That means that the United States is still in for now, but what role it will play in the negotiations this year and beyond isn’t entirely clear. It has a more modest delegation than in previous years, but some of the career civil servants who are here are still tasked with the basic work of developing the Paris rulebook. The US is along with China notably chairing the working group on developing the transparency rules.

With that said, it is pretty clear that the leadership that the United States sought to display during the Obama administration has largely dissipated or is on indefinite hiatus. That is the impetus for today’s side event.

Core Functions of the Regime

I approach this first by trying to identify the core functions that the climate regime collectively needs to perform.

For me, these functions include:

- Information provision on the science of climate change, on who is doing what, and on solutions

- Agenda-setting on heightened ambition,

- Elaboration of rules, most notably on transparency

- Mobilization of finance and technology for both mitigation and adaptation, and finally,

- Coordination of action to ensure that actions by different players and in different sectors aggregate and collectively generate results that are both as fair and as efficient as possible.

I think we then have to ask ourselves 4 questions:

(1) What actors are performing those functions?

(2) Are those functions being adequately fulfilled?

(3) Where will the US federal government be missed most?

(4) Are and can other actors step in and lead in the absence of the United States?

By leadership, I mean the ability to set the agenda and mobilize others through the power of example, through capacity to convene, and through market power and material resources.

So, without further ado, I will turn to our panel. We will we go in alphabetical order by last name, starting with Aimee, Sander, Arunabha, Angel, and then Axel. I’ll close with some short summary observations.

We’ve now heard from our panelists, and I wanted to summarize and give you my read of the situation.

How Is the Regime Working?

As for the functions that I talked about earlier – information, agenda-setting, rule-making, mobilization of finance, and coordination, there are some that are being performed better than others, but collective performance is not sufficient to avoid dangerous climate change.

In terms of information collection and provision, I feel confident in the capacity of the IPCC and national science programs continue to have capacity to inform us about the science of the problem with increasing confidence and specificity. Other areas like reporting on emissions mitigation hinge on success here and COP24.

On agenda-setting and ambition, we clearly have some ways to go. As the UNEP gap report released last week showed, collective commitments under Paris are only about 1/3 what they need to be to have a good chance of remaining below the 2 degree target.

On rule-making, the US presence at this COP as co-chair of the committee on transparency suggests some possibility that a low-key presence could push China to embrace more robust uniform rules, at least that the US and China be treated equally. I guess we’ll find out.

On finance, much attention has been paid to the fact that the US remaining contribution to the GCF of $2 billion won’t materialize, but all of that is a side show from the wider commitment to mobilize up to $100 billion per year by 2020, which itself was inadequate. So, if we are talking about unlocking finance, we have a long way to go.

On coordination, the UNFCCC secretariat organizes the negotiations but the regime is bigger than this gathering. We saw world leaders convene in September in New York for Climate Week. President Macron will be hosting leaders again next month. Governor Brown will be hosting his own climate gathering in September of next year in the lead up to climate conference in Poland. We have to ask ourselves how do these various gatherings cumulate, aggregate?

What Next?

And, given all of these inadequacies, what next?

I think we need some strategic moonshots here. We always did, even if Donald Trump had not become president.

On the mitigation side, we should think about medium to long run sector-specific decarbonization goals. We should start first with ensuring that previous promises were kept. The 2014 New York Declaration on Forests was a breakthrough and all those involved, namely as it relates to palm oil, need to shape up.

In other areas like transport, with China’s hint that future cars will be all electric, we have an opportunity to make that the emergent norm in this space sooner rather than later.

Of course, that requires that the source of electricity be carbonfree. Here, we are finally on the cusp of a renewables take off around the world. But, there is at least one major hitch which is energy storage. Arunabha has called for a consortium effort for India to host an open source partnership and make energy storage at scale workable.

Another opportunity is a concerted international effort to address Air Pollution in major urban air areas which can yield co-benefits for climate change . Here, Beijing and Delhi may be able to learn much from Seoul, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and London.

On finance, is both inadequate and heavily skewed to mitigation. It should become a major point of corporate philanthropic giving and for all billionaires to support adaptation efforts in the developing world. On mitigation, Arunabha here again has an interesting idea of risk pooling to crowd in private sector finance. I would also make greening the AIIB a major sustained campaign.

Different actors will likely be needed to step up and lead, and it is hard to see any single nodal actor, what Arunabha calls “distributed leadership.” But, there should be a way for a loosely coordinated high-ambition coalition, what my friend and mentor Nigel Purvis calls the Battlestar Galactica ragtag fleet, to come together on the lonely quest to decarbonize the world.

In sum, the loss of leadership by the United States federal government is a problem in the short-run, but the rest of the world, including subnational actors, can make strategic interventions that blunt the full force of the US departure by maintaining and even increasing their own ambitions and ensuring that the Paris architecture is as strong as it can be, until the day voters in the United States come to their sense and elect a responsible president again.

I am not confident that holding the line will be all that easy, but I am more optimistic, especially in light of the Virginia and New Jersey state elections this week, that we will have a decent chance of picking up the pieces and jumping back in in 2020, and I can assure you that Americans who care about climate change will be fighting like hell for that every day between now and November 2020.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks