This is a guest post from Jonathan D. Caverley, Associate Professor at the Naval War College and Research Scientist at MIT, and Monica Duffy Toft, Professor at Tufts University, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

The program for the 2019 International Studies Association (ISA) meeting has been released, and International Relations Twitter has feelings about it. The stakes of inclusion on the program are not small. Presenting a paper at ISA is frequently an essential step towards publication in the field’s refereed journals, these meetings provide valuable networking space, travel funds are often predicated on a paper being accepted, and ISA often takes place in great cities…as well as Atlanta (we kid!). Because of the value of these slots and their growing scarcity, we believe a little more transparency about how decisions are made in accepting participants onto the program is helpful. We therefore write this post to share lessons we have learned as the co-chairs of the ISA’s International Security Studies Section (ISSS) program for the 2019 Annual Conference.

We do not think we have the last word on how to do this, which is one of the reasons we are writing this. Since both of us have, like most program chairs, vowed to never (ever!) do this again, this blog post seeks to lay out some ideas for future chairs. We write this with the understanding that so much of the knowledge of how the process works is unavailable to many scholars, particularly junior ones. We realize our fortune in having received great mentorship at a top American PhD program, and having had jobs at well-resourced and networked departments since. Collectively we have been in this business for several decades. And yet we still came to the process with little idea of the many elements of conference program selection and management we actually encountered.

What follows are ten facts and lessons that jumped out at us. We hope that this will trigger a discussion and the generation of other lessons.

1. What the field cares about

We were struck by what topics were popular and suspect the Duck’s readers will be as well. First, it was pretty diverse substantively. We saw little correlation between quality of the submission and area of inquiry, so the program is roughly representative of the distribution of submissions.

We coded the accepted panels based on broad categories. The top 5 were “Intrastate conflict” (14 panels), “Nuclear” (11), “Terrorism” 11, “General IR” (10), and “Alliances” (10). There were a lot of panels and papers about China, most written by scholars outside of the United States. Cyber has become a major research effort (6 panels), and we found that civil-military relations to be particularly numerous and strong among the submissions (leading to 6 panels on the program).

2. ISSS is big

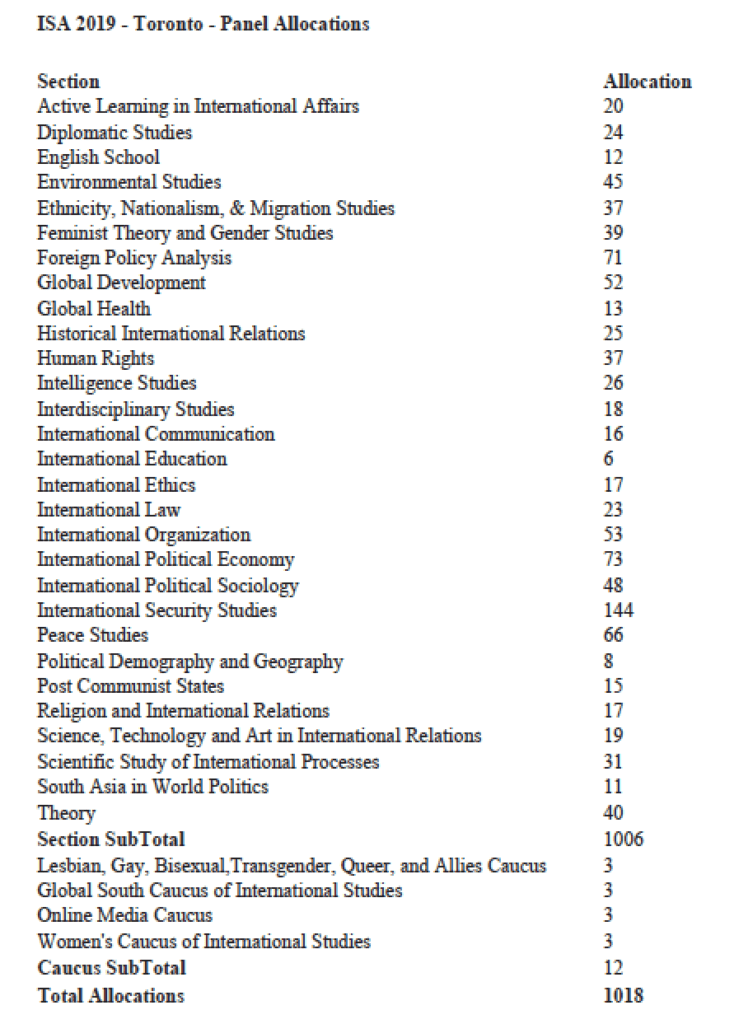

We received 121 (mostly) fully-formed panels and roundtable submissions and 688 individual paper submissions with ISSS as their top choice. ISA allocated our section 144 panels, comprising five (not four, nor six) panelists each for the paper panels and up to roughly eight participants for roundtables. (In terms of panel allotment the next closest section was Foreign  Policy Analysis, which was allocated fewer than half of our ours at 71). Ultimately, we were able to sponsor or co-sponsor (of which more later) 154 panels.

Policy Analysis, which was allocated fewer than half of our ours at 71). Ultimately, we were able to sponsor or co-sponsor (of which more later) 154 panels.

Sorting through this number of submissions was time consuming and it was not made any easier by the software, which took a good amount of time to learn. We never did master it.

3. Conference software drives too many decisions

We all know that software drives how we perceive the world and shapes our decisions. It should not surprise that the clunky software for conference programs does this to a tremendous degree.

There was no way to track participation. We wanted to make sure that scholars with worthy proposals made it onto the program before we gave a second slot to someone. This was extremely hard to figure out. Furthermore, we ideally tried to make sure that if your paper proposal was accepted, we could then assign you to a chair or discussant role. This was not possible! At one point we had placed a colleague into eight separate roles (the software was less strict than ISA on participation)! So, future iterations of the software should allow us to track who we have selected and in what capacity.

Building a diverse program on intellectual and other fronts was a challenging but satisfying aspect of this gig, but it is not always easy to discern gender, geographic location, country of origin, and other demographic information from the information provided. There were cultural roadblocks, such as our unfamiliarity with the typical gender associated with many non-European names. It would help if people could choose among some identities (gender, country of origin) on their proposal. We would love to hear suggestions on this front.

4. Panel attendance drives panel allotments…and perhaps panel makeup

Section membership size matters, but so too does participation at the conference. Panels are doled out by the ISA conference chairs based on a somewhat complicated algorithm.

This process rewards panel attendance at the meeting. Thus sections are incentivized to have panels with big names on them, which of course tend to be senior, male, white, and from a prestigious few universities. This almost certainly affects smaller sections more than ISSS, but the incentive needs to be recognized and perhaps adjusted. But for now the key takeaway is that if you want more panels for your section next year, then you should attend a lot of those panels this year.

5. All-male panels were not much of an issue

Our large section gets plenty of panels, so we felt less pressure on the attendance front. This pressure was lessened further because, at least in our section, all-male panel submissions were delightfully rare. There were nine “manels” among the 121 preformed submissions. There are no manels on the program. We found it quite easy to create panels with at least two women, at least one of them presenting a paper.

6. Paper or panels?

Pre-formed panels made our job easier, but it also rewards and deepens preexisting networks of scholars. ISSS, and the larger ISA, therefore have a policy of dividing the panel allotment so that pre-formed panels and papers have roughly the same odds of being accepted. We did not know this policy existed until we served as chairs, but found this to be a fair division.

7. Clear titles and tags improve papers’ and panels’ chances

What improves the chances of a paper’s acceptance? At least for us, the first pass through the submissions was a frantic sorting of papers into somewhat coherent proto-panels. These were driven by titles and tags. When we were looking for a fifth paper for a panel, tags were the first search term we used, largely because the software privileged this sorting mechanism.

We then read through the abstracts to see if the proposed project looked coherent and somewhat in keeping with the panel theme. The abstract helped us understand the method and the fit.

So, tag your paper with keywords that help the co-chairs create coherent panels: “civil war” is much more effective than is “international security”. Using “Civil war termination,” “Civil-military relations” and “taxes” is even better!

Also, clever titles are not helpful. Being clear about what your paper addresses facilitates the selection for co-chairs who have to make up panels from these paper submissions. Our sense is that straightforward titles did better than the more convoluted ones. Just consider that when we made panels, having been inspired by Thomas Leeper, we labelled them simply and uncreatively as in “Tactics of Terrorists” and “Rebels and Civil Wars”.

8. System-driven methodological agnosticism

Because of the software, the quantity of submissions, and our own intellectual commitments, methods drove very little of our selection process. Scholars rarely put their method in the title after all. We were struck by the number of critical and post-positivist papers submitted to ISSS and did try to make sure they were represented throughout the panels. But the panels are more likely to have substance in common rather than method.

9. Cross-sectional dynamics, especially caucuses, matter

Proposals are released over time in order of the proposer’s choice of section. Given the size of our section, if a paper or panel did not put ISSS as its first choice, we simply did not look at it. Once second and third choice submissions were released to our queue, the system stopped enumerating them at 999.

We were blindsided by the sheer number of cross-section panel proposals we received, over 70. Depending on number of sections involved, co-sponsoring a panel counts as half or a third of a panel in one’s own allotment (with a maximum of three co-sponsors). This creates a complicated strategic environment, with a lot of collegial horse-trading. In hindsight, we wish we had a better plan to manage this.

We also had the luxury of having others come to us. This was largely because we were so buried going through our own submissions before we could even think about co-sponsoring. We tried to be fair about distribution (and paid a lot of attention to the diversity of the proposed panels…we got quite a few all male co-sponsoring offers). We also really appreciated section chairs contacting us directly via email, although this did get overwhelming. We apologize to all our colleagues for not responding in a timely manner! Nevertheless, in this case it kept their section co-sponsorships in our sights and we were able to respond once we sifted through our submissions. Future program chairs should expect a lot of email.

We cannot stress how helpful caucuses were. If done well, and Mariana Kalil at the Global South Caucus did this very well, caucuses punch above their weight (i.e. in terms of panel allocations). A caucus that reached out to our larger section with a pre-formed panel was pushing on an open door. We got several excellent panels from “smaller” groups who stated frankly that they wanted to use their very few panel allotments for other things, and would we take over as sponsor (or co-sponsor with another of the larger sections)? As long as the panel was interesting and it was linked to security (not always the case), we were often thrilled to diversify our slate in both substance and in representation.

If you think your paper or panel meets the goals of a caucus like the Global South, submit!

10. Better together

We are grateful that we each had the other as co-chair. We had worked together in the past, so knowing and trusting one another made it easier to make some very difficult decisions about which papers and panels to accept onto the program. Also, it helped that we worked in different subfields in the discipline. Between the two of us we have a pretty good grasp of the scope of topics, papers, and research across the ISSS section to make decisions. We recommend, especially for large sections, not doing this alone!

We received immense support from a talented and hard-working graduate student, Polina Beliakova from Tufts Fletcher School. For graduate students, it can be an opportunity to earn a stipend, work with senior scholars, get a snapshot of the trends in the discipline, and learn how the ISA program sausage is made early in your career. Resources are scarce, but sections and the larger ISA should consider institutionalizing RA funding.

We are also grateful to the larger ISA program committee. They were very clear in their expectations, gave us appropriate timelines, and did heroic work deconflicting programs and making sure we had not screwed anything up. The level of effort we put in pales in comparison to the efforts of Nukhet Sandal and Jenifer Whitten-Woodring.

This is not the last word

We would love to hear from other program chairs. Also, if anyone has any questions that we did not address, perhaps we could respond in a follow-on post.

For future chairs, I’m sure you are able to glean that this is a lot of work. However, there are satisfying aspects: working closely with a colleague on an intellectual challenge, training (and learning from) a graduate student, and learning the overall trajectory of where the field is going.

See you in Toronto!

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

Hello :)

My paper is on a panel in the junior scholar symposium. I had a feeling I got accidentally selected to present at the conference and I didn’t expect it at all. I was quite surprised and overwhelmed that all the others in my panel were from the best universities and ivy leagues. I don’t represent a university, but my workplace.

This explanation was quite comprehensive and I am grateful for this opportunity for opening up an avenue for someone like me from Sri Lanka.