Guest post by Tiffany S. Chu, Alex Braithwaite, Faten Ghosn, and Justin Curtis

Plans to fund a border wall at the U.S.-Mexico border are troubling D.C. politics. During his campaign for the presidency, candidate Trump promised a wall would be built to reduce security issues he associated with existing border policy. In the longest government shutdown in history, Democrats in Congress refused President Trump’s demand for $5.7 billion in funding for such a wall. While the government eventually reopened, ongoing negotiations in Congress to reach a border security deal ahead of another shutdown seem unlikely to reach an agreement that will please the President. In the meantime, troops have been deployed to stop a so-called migrant caravan from crossing the border while anti-wall rallies are held only a mile away.

This is not the only case of political leaders scapegoating migration as a threat to national security. Proponents of Brexit claim it would end the freedom of movement and severely limit rights for migrants living in the U.K., beyond breaking free of the Common European Asylum System. From a more sympathetic perspective, the Pope, too, has been making a priority of highlighting the plight of refugees. Pope Francis met with a Spanish group rescuing migrants in the Mediterranean, and has plans to visit a training institute aimed at deradicalizing Muslims to counter terrorism in Morocco. Moreover, most terrorist plots in Europe are carried out by European citizens, not newly arrived migrants from these areas. Nevertheless, we have seen a rise in anti-immigrant, anti-refugee, and anti-Muslim attitudes manifested into policies treating terrorists and migrants similarly.

The issue with many of these policies is the West-centric focus of migration and security. The media attention tends to frame the higher than average flow of migrants as relentless, coming from both land and sea. Yet, managing migration is a far greater security challenge to weaker states than post-industrial Western countries. We believe the focus needs to be shifted to better understanding the considerable humanity of host communities who take in large refugee populations and often struggle under the burden this represents.

Over 80% of all refugees live in countries neighboring their home country; this is a fact that underscores the hyperbolic reaction to a refugee “crisis” in Europe and the United States. In the early years of the Syrian civil war, a great deal of heart and compassion was demonstrated by populations and governments next door to the crisis. However, public support for hosting has waned considerably over time, with cries of refugees overstaying their welcome and a perception of security concerns linked to their presence.

One state taking in many Syrian refugees is Lebanon, which hosts the largest number of refugees relative to its national population. Lebanese public opinion of hosting mirrored the trend of declining support: initially, most Lebanese felt sympathy toward those fleeing. However, due to a variety of attacks by Syrian militants, year by year the number of Lebanese individuals feeling unsafe because of the Syrian refugee presence rose from 25% in 2013 to 51% in 2017.

In two new articles, we ask what factors can affect public concerns about hosting refugees? Our first paper tests two theories of opinion formation of out-groups. The first is contact theory, which suggests interaction with an out-group helps reduce prejudice as well as improve prospects for integration and cooperation. This is what Pope Francis hopes his visits with migrants and Muslim leaders will bring about in attenuating fears of migrants who journey to Europe. The second is empathy driven, which draws upon a growing literature on how experiences of conflict, displacement, and repression can make individuals more compassionate in the future toward other groups going through similar situations.

We test both logics using a novel data set of 2,400 survey responses from Lebanese residents who were at least 5 years old when the Lebanese civil war began in 1975. The survey was conducted in the summer of 2017, five years into the period of hosting refugees from Syria. We compared individuals who experienced violence and/or became displaced due to the civil war that ended in 1990. We also asked respondents about the extent of their contact with Syrian immigrants and those who recently chose to settle in Lebanon.

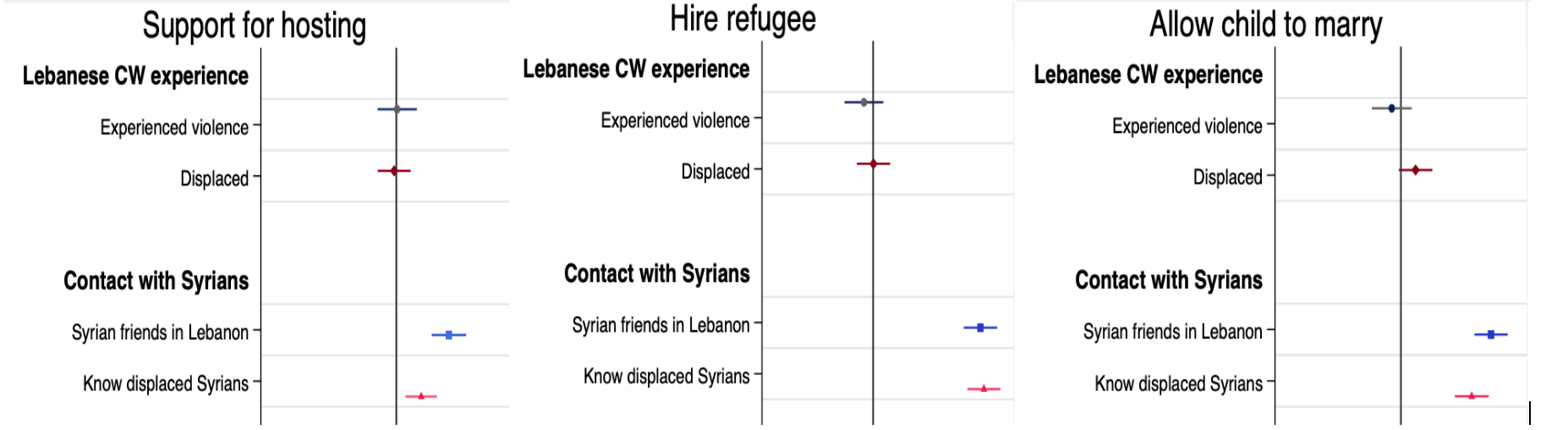

Our results demonstrate that historical exposure to violence and experience of displacement have no discernable impact on individual attitudes toward hosting refugees. We find much stronger evidence that positive stances toward hosting refugees are identified by Lebanese who have contact with Syrians. We find robust evidence of these relationships drawing upon three indications of support for refugees: a general aggregate support for hosting, whether they would hire refugees, or allow their child to marry a refugee. Our findings suggest living through a civil war and being exposed to violence by itself are not associated with sentiments toward refugees. This is likely because Lebanon and its residents have been over-extended by so many years of hosting refugees.

Figure 1: Estimated effect of civil war experience and contact with Syrians on a variety of support for refugees. Points to the left of the center vertical line indicate less support while points to the right indicate more support

But contact alone is not the only way negative attitudes and concerns regarding the risk of hosting refugees can be attenuated. In our second study, we exploit exogeneous variation in the timing of violent events linked to refugee populations that occurred during the collection of our survey data. The key events in question are an attack against a refugee camp by Syrian militants on June 30, 2017 and an offensive on July 21, 2017 against these militants. The June 30th attack was comprised of five suicide attacks against the Lebanese military near Arsal, a town close to the Syrian border. The attack occurred during a raid on the Al-Nur refugee camp as part of an ongoing security sweep by the Lebanese army to arrest militants and seize weapons that had been smuggled over the Syrian border to be utilized in attacks elsewhere in Lebanon. In response, Hezbollah launched an offensive on July 21 to remove militants from refugee camps near Arsal.

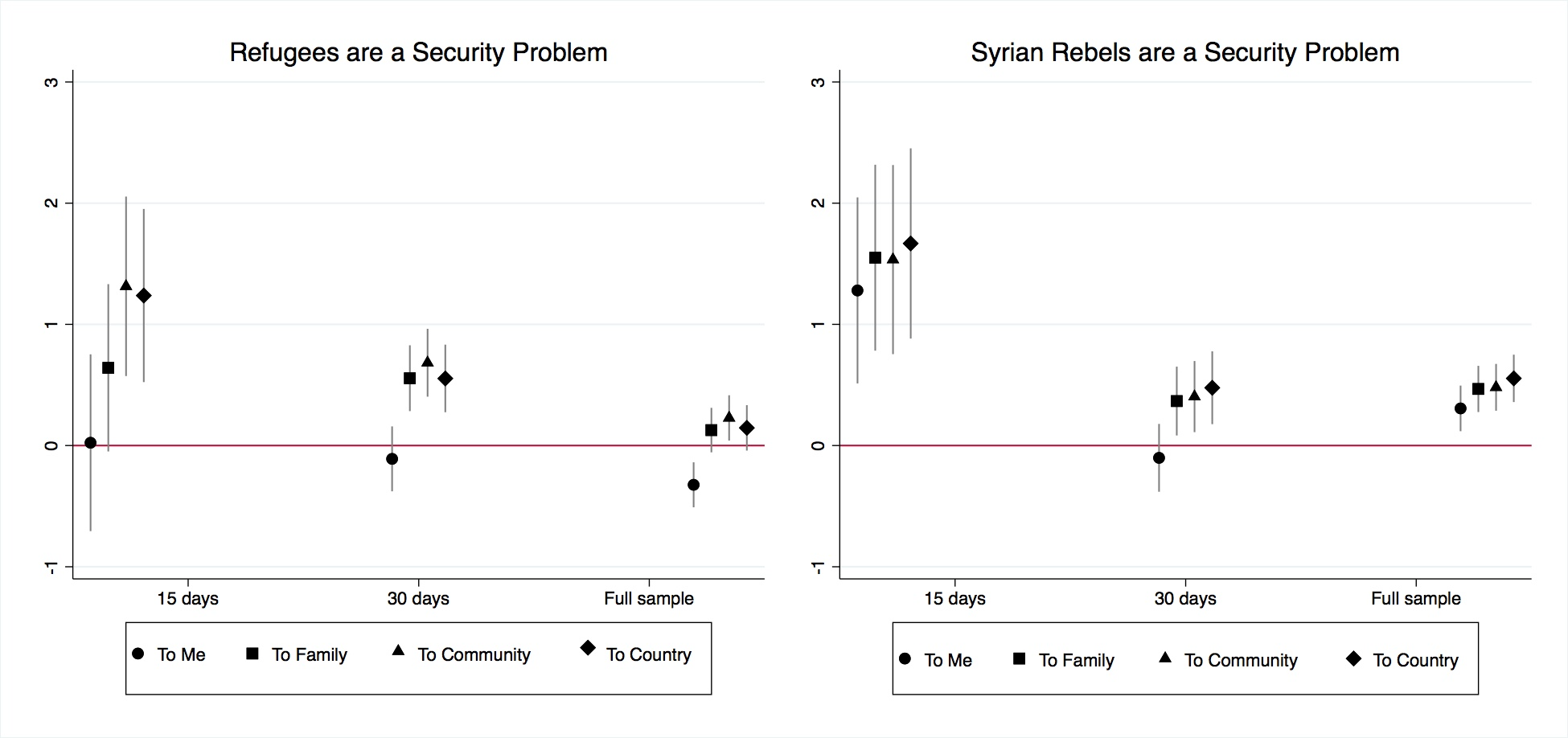

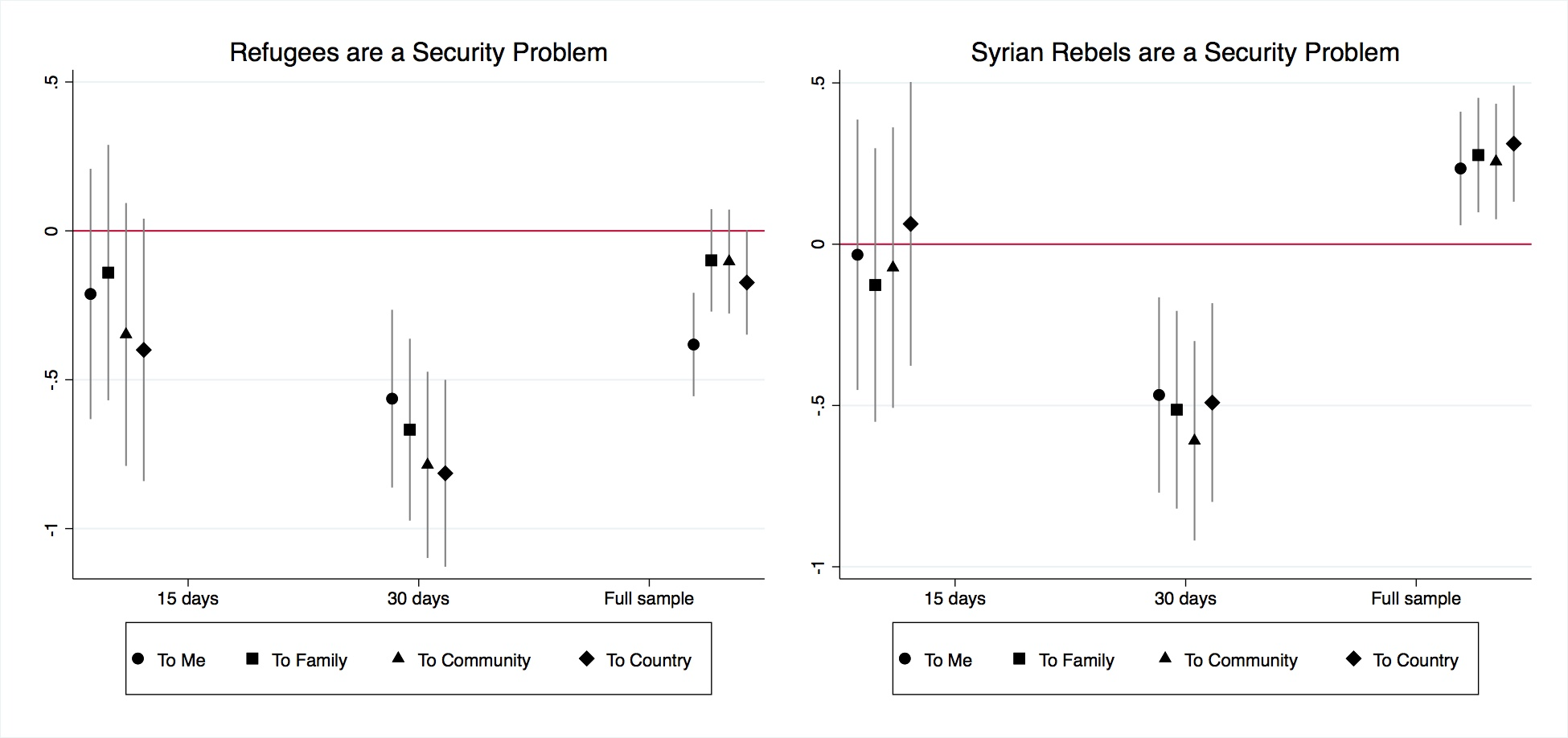

We find those surveyed 15 days after the June 30 suicide attacks are more likely than those surveyed prior to the attack to believe refugees and Syrian rebels are a substantial security problem. Yet, within 30 days of Hezbollah’s efforts to counter Syrian rebels, respondents report feeling that refugees, generally, and Syrian refugees, in particular, are actually less of a security problem. This suggests that violent events designed to secure the country can actually mitigate fears associated with hosting refugees.

Figure 2: Estimated effect of June 30 suicide attacks on whether refugees and Syrian rebels are a security issue. Points above the horizontal line indicate greater risk to security while points below indicate less of a risk.

Figure 3: Estimated effect of July 21 offensive on whether refugees and Syrian rebels are a security issue. Points above the horizontal line indicate greater risk to security while points below indicate less of a risk.

In sum, our studies suggest encouraging contact between local communities and refugees, as well as efforts to eliminate security threats can, respectively, serve to improve levels of support for hosting refugees and reassure a population’s perception of the threat posed by hosting refugees. First, there needs to be a shift in attention toward states hosting the most refugees because they take on the largest burden yet have the fewest resources.

Policy makers should also strive to distinguish between actual security threats and innocent civilians, who might happen to share militants’ ethnicity, religion, or nationality. When there is a spillover of violence and an actual threat to security, meaningful policy is the ability to differentiate between the perpetrators and displaced individuals seeking safe haven. Indeed, we only find support for the argument that security forces’ efforts to root out militants from refugee populations effectively reassure hosting populations’ perceptions when security forces are acting in direct response to particularly violent, salient, and identifiable attacks by militants embedded among refugees. Thus, indiscriminate deterrent policies, like building a wall, are unlikely to affect a population’s perception of threat.

Furthermore, demonstrating control over the security of their country and highlighting that attacks are isolated incidents can mitigate the perceived threat of providing safe haven for displaced populations and lower the number of attacks against refugees.

Note: The research reported here was funded by award W911-NF-17-1-0030 from the Department of Defense and U.S. Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory under the Minerva Research Initiative. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Department of Defense or the Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory.

Amanda Murdie is Professor & Dean Rusk Scholar of International Relations in the Department of International Affairs in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Help or Harm: The Human Security Effects of International NGOs (Stanford, 2014). Her main research interests include non-state actors, and human rights and human security.

When not blogging, Amanda enjoys hanging out with her two pre-teen daughters (as long as she can keep them away from their cell phones) and her fabulous significant other.

0 Comments