Rubio’s civilizational appeals will backfire

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s speech at the Munich Security Conference demonstrated he is a...

“Fair Trade” and the revenge against the “Foreigner”: From Chamberlain to Trump

A century before Trump’s tariff threats, Joseph Chamberlain pitched the same idea: use duties as a “big revolver” to force rivals into “fair trade.” That history helps explain why “unfairness” rhetoric and coercive foreign policy keep returning when hegemonic powers decline.

What’s with all the racism?

I’ve been wanting to write this post for some time. But every week just brings more bad news. More...

An Accidental Academic: 20 Years Later

This is my 20th year at the University of Texas. Although my dad was a university professor,...

New

Rubio’s civilizational appeals will backfire

US Secretary of...

“Fair Trade” and the revenge against the “Foreigner”: From Chamberlain to Trump

A century before Trump’s tariff threats, Joseph Chamberlain pitched the same idea: use duties as a “big revolver” to force rivals into “fair trade.” That history helps explain why “unfairness” rhetoric and coercive foreign policy keep returning when hegemonic powers decline.

What’s with all the racism?

I’ve been wanting...

Featured

Farewell

The Hayseed Scholar podcast has come to a close. In this farewell episode, Brent's brother...

Benjamin de Carvalho

Dr. Benjamin de Carvalho joins the Hayseed Scholar podcast. Ben was born in Switzerland to a...

Who wants AI in the classroom?

I get emails. Sometimes they find me well; sometimes they try to convince me that I need to bring...

Recent

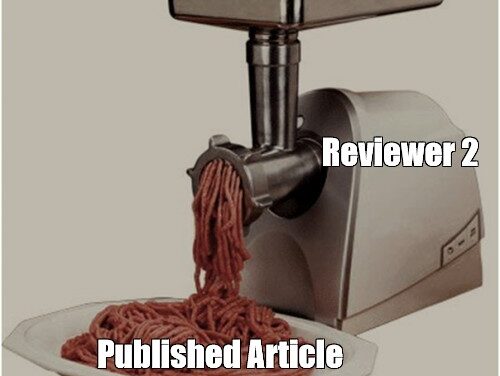

How To Review Efficiently and Fairly

Instead of Dry January, I’m going review free for January after having nearly 80 review...

Renee Goode and the limits of false terrorism charges

On 7 January, US Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents opened fire on Renee Goode,...

Trump, US foreign policy and Venezuela: Aberration or Honesty?

In my international relations classes, I encourage my students to not just express their (mostly...