Over recent days, however, we’ve seen a flurry of talk about the end of Pax Americana and the coming of multipolarity.

It wasn’t long ago that America was the “New Rome”. In fact, only a few months ago did I finish Deepak Lal’s In Praise of Empires, in which he argues that “the contemporary academic theory” that “Ph.D. practitioners have learned has by and large been devised for the anarchical European state system which developed with the fall of Rome.” How “to maintain an empire is not what they have been taught in their classrooms” (p. 78).

International-relations pundits and even–I know this may come as a shock–international-relations theorists are notorious fashion victims.

The Japanese economy is kicking butt in the 1980s and we’re all going on about “Japan as Number One” and “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers”.

Then the Cold War ends and a lot of people start warning about fleeting unipolarity and the coming multipolar order.

Next we’re in the middle of the 1990s and people are like “wait, where’s the mutipolarity?” The next thing you know everyone’s going on about how “unipolarity is stable” and the puzzle of why no one is balancing against the US. After September 11, 2001, the big guns start talking “American Empire” and suddenly we’ve got to worry about “soft balancing.”

Now American primacy is collapsing. Or is it? Let’s all step back and take a collective breath.

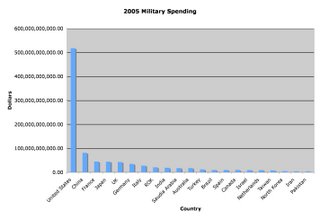

First, the global distribution of power hasn’t changed overnight. The world is still militarily unipolar and economically multipolar. The chart below shows the CIA Factbook data on 2005 military spending. I’ve listed 1-18 and, for good measure, stuck in North Korea (22), Iran (25), and Pakistan (26). The US, as you can see, dwarfs its nearest peer competitors, China, France, and Japan. The reality of these figures becomes even starker when one considers that, of all the countries in the top 18, only China and India aren’t close US allies and only China gives military strategists heart palpitations. Most scholars talk about unipolarity as a condition in which the most powerful state faces no conceivable coalition capable of matching its capabilities. The position of the US still fits that definition.

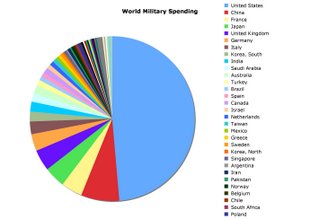

Just for good measure, here’s a pie chart that shows the US share of global military spending.

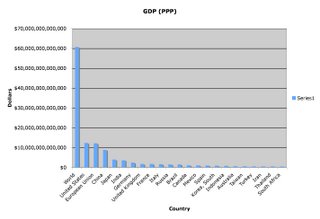

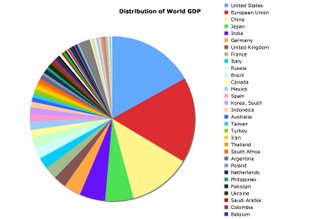

The economic situation remains multipolar. No real surprises here.

If China wants to become a peer-competitor to the United States, then we should expect military unipolarity to end sometime before the Chinese economy overtakes the American economy. Given that projection–and predicting trends this far out is very dangerous–the US is still likely to enjoy a period of military supremacy unmatched, at least in the European experience, since the collapse of the Carolingian Empire.

I fully realize that counting tanks, aircraft carriers, and economic output is a crude measure for power. So let’s look at Timothy Garton Ash’s nicely worded synthesis of all the factors that might make this a multipolar world:

The first, and most familiar, is the rise or revival of other states – China, India, Brazil, Russia as comeback kid – whose power resources compete with those of the established powers of the west.

See above. “Compete” here should be read as “within specific regions.” Few preeminent powers–I would say “none” but I’m sure there’s an example or two to prove me wrong–have faced a total absence of competitors. But China and India are not year peer competitors. Russia? Not even close; there’s no sign of an imminent revival of Russian military prowess. Whether their oil revenues will translate into future prosperity remains highly uncertain.

The second is the growing power of non-state actors. These are of widely differing kinds. They range from movements like Hamas, Hizbullah and al-Qaida, to non-governmental organisations like Greenpeace, from big energy corporations and drug companies to regions and religions.

Transnational actors do constitute a serious problem for the United States–and for a lot of other states as well–but these forms of “asymmetric warfare” and “proxy warfare by states” primarily check and limit US influence. They demonstrate that the US is not omnipotent.

Unipolarity, however, never implied the omnipotence of the United States. This remains, arguably, the major mistake of the neo-conservative movement: they conflate the fact of American military primacy with the notion that the US has a free hand to remake the world–or, at least, regions of the world–as it sees fit. The current environment implies not the brute reality of multipolar chaos, but the deleterious impact of ill-adised and poorly implemented policies on the scope of American influence. This is a theme I’ll return to later.

A third trend involves changes in the very currency of power. Developments in technologies with violent potential mean that very small groups of people can challenge powerful established states, whether by piloting an aeroplane into the World Trade Centre in New York, targeting a missile at Haifa, taking on the US military in Iraq, bombing the London underground, or squirting sarin gas into the Tokyo subway. Developments in information technology and globalised media mean that the most powerful military in the history of the world can lose a war, not on the battlefield of dust and blood, but on the battlefield of world opinion. If you look at the precipitate decline in US popularity since 2002, charted by the Pew Global Attitudes polls even in countries traditionally sympathetic to Washington, you could argue that this is what has been happening to the US.

These changes do not as yet, I would argue, suggest that power has shifted as radically out of the hands of states, let alone the United States, as Ash implies. Al-Qaeda can kill three thousand Americans, other terrorist cells can kill hundreds, quasi-state actors supported by states may show a surprising degree of military prowess, but they cannot inflict the kind of massive damage that militarily capable states can accomplish. Compare the damage an all-out HIzbullah attack is inflicting on Israel with what the IDF is doing to Lebanon. And despite arguments about whether the IDF’s actions are proportionate or whether the IDF isn’t being discriminating enough in its attacks, the fact is that, if they wanted to, the IDF could be doing a lot worse to the Lebanese population.

Now, consider what the United States could do if it took its glove off, engaged in actual war mobilization, and so forth. I have no doubt that American and international public opinion, let alone basic prudence, limits the United States from becoming a full-blown, stategic-bombing, nuclear-weapons using, war machine. But when we think about unipolarity and its implications, we need to recognize that these unrealized capabilities render it impossible for its nearest competitors to contemplate a great-power conflict waged against it. The world is far, in military terms, from a multipolar distribution of power.

The state of American hegemony, however, remains in question. While some pundits and scholars treat unipolarity and hegemony as synonymous, we should recognize important differences between the two concepts. Unipolarity is a distribution of power; hegemony comprises a condition in which a preeminent power creates a quasi-hierarchical order by establishing rules of the game and providing public goods. Bush foreign policy may be jeopardizing American hegemony, and the kinds of checks on US influence discussed above represent serious threats to America’s hegemonic influence. But, to the extent that our current predicament stems from hegemonic mismanagement, it is possible that a new, more capable Republican or Democratic administration could turn things around.

More on hegemony, the “Pax Americana”, and American empire in the next installment.

Filed as: Iraq, Lebanon, Israel, multipolarity, hegemony, and unipolarity

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

0 Comments