The judicial organ of ECOWAS has found the government of Niger guilty of failing to prevent slavery within its borders.

The judicial organ of ECOWAS has found the government of Niger guilty of failing to prevent slavery within its borders.

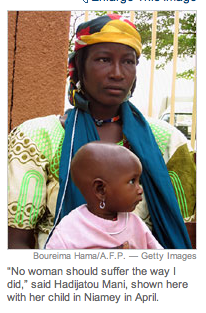

“The landmark ruling, the first of its kind by a regional tribunal now sitting in Niamey, Niger’s capital, ordered the government to pay about $19,000 in damages to the woman, Hadijatou Mani, who is now 24.

Slavery is outlawed throughout Africa, but it persists in pockets of Niger, Mali, Mauritania and amid conflicts like the one in northern Uganda. Antislavery organizations estimate that 43,000 people are enslaved in Niger alone. Ms. Mani’s experience was typical of the practice. She was born into a traditional slave class and sold to Souleymane Naroua when she was 12 for about $500. Ms. Mani told court officials that Mr. Naroua had forced her to work his fields for a decade. She also claimed that he raped her repeatedly over the years. Ms. Mani brought her case to the court this year, arguing that the Niger government had failed to enforce its antislavery laws.

This is a significant ruling not just in Niger and not just in regards to the slave trade. However, I wonder if it’s significant in the ways that some antislavery activists in the region are claiming. For example:

“For 17 years, we have been working towards bringing slavery to the attention of the authorities,” said Ilguilas Weila, president of Timidria, a Niger antislavery advocacy group, in a statement. “This verdict means that the state of Niger will now have to resolve this problem once and for all.”

That’s not at all clear to me, since like some other regional courts the Community Court of Justice does not actually have the power to enforce its rulings. As my former professor Robert Darst liked to say, the absence of teeth means it has less power than Judge Judy, whose guests sign contracts agreeing to abide by her rulings; the contracts, though not the rulings themselves, are enforceable through tort law in a US Court. By contrast, no authority will punish a state who simply ignores such rulings; so they tend to be what states will make of them. There is a real question as to whether Ms. Mani will see a penny of this money, or whether the shaming effect of this ruling will have a long term impact on the enforcement of anti-slavery laws in Niger.

But it may. It is notable that the Niamey government does have such laws on the books and is not in the business of openly condoning or winking at slavery. In recent years the policy has been one of denial (as opposed to justification), suggesting a growing, acknowledged opprobrium; and what this case does is invalidate such denials. This may force the government to adopt stronger anti-slavery measures, since it clearly wishes to convey that it opposes the practice. It’s one thing to deny a practice is occurring; it’s another to excuse it once public evidence is presented by a neutral third party. The press attention to the verdict will help.

The case will also draw much-needed attention to the persistence of slavery in West Africa (let’s hope that it doesn’t obscure similar practices elsewhere in the world). Anti-slavery activists claim there are at least 40,000 people kept as slaves in Niger; smilar conditions exist in Mauritania and Mali.

Beyond the immediate impact on Nigerian law enforcement (if any), on Ms. Mani, or on anti-slavery activism, the case will have an impact in another respect: it is one in a growing trend in international jurisprudence that places the responsibility on states for human rights abuses inflicted not by agents of the state, but by citizens on one another. We can expect to see this case cited by activists and lawyers concerned with many other private human rights abuses such as domestic violence, honor killings, and hate crimes.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

0 Comments