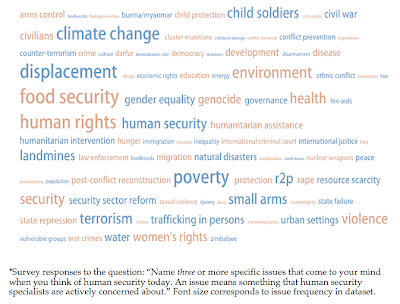

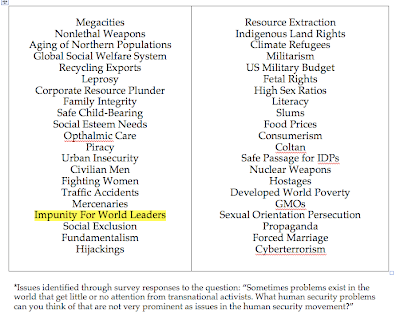

Earlier this year I threw up some results from a survey of folks interested in the concept of “human security,” in which my research team asked them to name the most important items on the human security agenda; and also to answer the question: “What problems do you know of that are not getting enough attention from the human security network?”

A first cut at coding this data shows highly salient issues include the following:

Problems not receiving enough attention, mentioned by at least one respondent, included megacities, leprosy, cyberterrorism, social exclusion, traffic accidents, high sex ratios, and “liberation of hostages, famous or not.”

One of these low-salience issues in particular stayed in my mind this week as I kept an eye on the news: “Impunity for world leaders who committed war crimes or crimes against humanity while in office.” It didn’t make the NYTimes headline this morning, but if I heard Bush correctly yesterday, he basically admitted to having signed off on torturing detainees during his administration.

Let’s leave aside the fact that “sure, I tortured” ranks pretty high among those things you’re not supposed to say as a sitting head of state, even if you’ve been there done that. Really, the important question is what the Obama administration should do about this legacy once taking office. Not about reversing Bush’s torture policy, which is largely a given. About holding the previous head of state accountable for that torture policy. And yes, it’s quite interesting to see so little attention to this building a norm to do precisely that. Sure there’s the international criminal court, but that’s an institution with a limited mandate and short reach. What about the responsibility of new governments to hold their predecessors accountable for crimes committed while in office? What about an international movement to create such a standard for democratic regimes?

At Harper’s, Scott Horton argues that there is a strong historical precedent for future leaders punishing a previous leader who willfully violates the laws of nations. Torture is a crime of universal jurisdiction, ranking right up there with genocide. The emphasis of activists so far have been simply to roll back Bush’s torture policy, but there are real questions to be asked about whether the international criminal regime has got to a point where it can reach and punish harms inflicted by the President of the most powerful country in the world.

As long as Bush stays in the US, the answer is probably no. But that doesn’t mean that the incoming administration couldn’t take steps, or that the human security community could not work harder to generate a sense of obligation for all governments to do the same.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

0 Comments