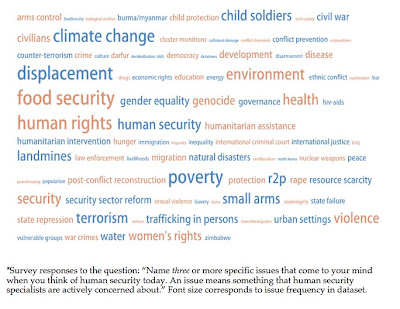

The human security advocacy network – a conglomeration of NGOs, IOs, state ministries, think-tanks, and independent opinion-makers working in the areas of development, human rights, humanitarian affairs, conflict prevention, environmental security and arms control – has generated a lot of new attention to emergent threats to individual freedom from fear and want in the past ten years. As the tag cloud below shows, landmines, child-soldiering, genocide, trafficking and climate change are just some of the human security issues that have been most prominent within this network lately.*

But what about the human security problems that did not get sufficient attention on this advocacy agenda in the last decade, and consequently suffer from neglect by global policy networks? To which pressing problems might human security advocates turn their attention in the next ten years?

To find out, this past fall I conducted six focus groups with a 43 global civil servants drawn from organizations identified as being prominent in the human security network, as part of an NSF funded project on global agenda-setting. Among the questions asked was: which important global social problems in these thematic clusters had received too little attention by human security professionals to date?

Some of the most frequently mentioned and interesting answers – issues that these practitioners see as pressing, neglected, and candidates for stronger advocacy in the next decade – are below the fold.

1) Opthalmic Care in Developing Countries. Good eyesight seems to many like a luxury in countries riven by malaria, HIV-AIDS and river-blindness, but as a health and development priority it may be one of the most important ways to help improve the lives of individuals in the developing world: according to the NY Times, a WHO study last year estimated the cost in lost output at $269 billion annually.

2) Gangs. Human security organizations pay a great deal of attention to armed political violence, but they tend to stress violence carried out by states, either in wars per se or against their civilian populations. And emerging attention to non-state actors tends to focus on terror groups or militias. Local violence not aimed at capturing the state but rather at holding turf in contestation with other local armed groups – and the role of gangs and cartels as parallel governance structures in many places now competing with states – is being overlooked by analysts and advocates of human security. In Mexico, for example, drug cartels bring in 20% of Mexico’s GDP, control significant portions of Mexico’s territory, possess their own armies. Columbian cartels are experimenting with submarines. Threats to human security in zones where these actors have a foothold are more complex than “combatting crime” or “preventing human rights abuses by states.”

3) Indigenous Land Rights. Perhaps this issue will get a bump with the release of James Cameron’s Avatar. While indigenous people have their own UN treaty process and the right to participate in UN processes, indigenous issues are relatively marginalized within the human security network, occupying little agenda space among organizations working this these areas. Since it is now becoming clear that many of the policy initiatives to stem climate change will negatively impact indigenous populations, perhaps the indigenous voice in world politics will get a little louder in the next few years.

4) Space Security. In 1967 governments signed the Outer Space Treaty, effectively demilitarizing the Moon and other celestial bodies and prohibiting the placement of nuclear weapons in orbit. Yet the treaty does not prohibit the placement of non-nuclear weapons in orbit, and according to the Center for Defense Intelligence, today space is becoming highly militarized as governments race to build anti-satellite weapons and space-based strike capabilities. These developments are prompting a movement to promote a new treaty on space governance. So far this idea has have limited impact in global policy circles, but it may an idea whose time is arriving. A recent report from Project Ploughshares argues that even the civilian uses of outer space represent human and environmental security risks, such as that posed by mounting orbital debris. And with the discovery of a perfect location for a moon colony being touted as one of the New Year’s top stories, the relationship between outer space and human security is bound to become more prominent in the next few years.

5) Role of Diasporas in Conflict Prevention. Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer may have attracted ire for their treatise on the Israel Lobby, but human security practitioners spoke repeatedly of the wider issue of which their case is a putative example: the impact of outsiders, particularly diasporas, in intractable conflicts worldwide. Focus group participants spoke of the role played by financial transfers and propaganda from ethnic brethren safe abroad in inciting violence within countries that puts civilians at risk and contributed to a spiral of violence – an argument also put forth recently by scholars at United Nations University. They also bemoaned the lack of a strong international norm against outside governments fomenting rebellion within states when it suits their purposes. It’s easy to see why such an ethical standard would go against the interests of some powerful states, but it’s also clear that such a norm might serve a useful conflict mitigation function.

6) Workers’ Right to Organize. The right to unionize is enshrined in human rights law but besides the International Labor Organization, very few human rights advocacy groups pay much attention to the rights of workers to organize and collectively bargain with the companies for which they work, or the responsibility of states to ensure this right is not violated. Organizations central to the human security network might follow the lead of smaller NGOs like the International Labor Rights Forum to address not only “humane working conditions” as defined by Northern advocates, but the right of workers’ to advocate on their own behalf about the concerns most pressing to them.

7) Waste Governance. It’s not sexy like climate change but it’s a significant environmental issue for billions of people worldwide. The safe disposal of human waste products is a prerequisite for human health and environmental well-being, yet in places like Africa, populations are rapidly urbanizing often in the absence of effective waste management architecture. As the International Development Research Center recognized ten years ago, this issue will need to become a priority for development organizations and donors in the next century.

8) Sexual Orientation Persecution. Gay, lesbian and transgender individuals worldwide face violence, stigma, and numerous forms of discrimination. Last month, the Ugandan government began considering legislation that would make homosexuality a capitol offense in that country; that they are now reconsidering this provision under pressure from donor governments points to the effectiveness of a strong international response to such human rights violations. Yet it has only been in very recent years that sexual orientation persecution has been recognized by mainstream human rights organizations as an issue meriting serious advocacy, and to date far too little attention has been paid to this very pervasive and widespread form of discrimination.

9) Water. Depending on who you ask, access to a sufficient clean water is a health issue, a development issue, a human right, and increasingly at the root of territorial conflicts globally. While the issue of water is already on the human security agenda, many focus group participants were adamant that much greater global attention and advocacy is required in the next decade to create genuine and inclusive governance over water as a planetary resource.

10) Familization of Governance. During the 2008 Democratic primary, some Democrats voted against Hilary Clinton for no other reason that this: they believed no political system was served by members of only two families – the Bushes and the Clintons – ruling a country for nearly two decades. Yet the US is hardly the worst country in the world when it comes to the monopolization of state power in the hands of a few wealthy families. In many countries, democracies and dictatorships alike, apportioning some high-level positions through kin networks rather than through merit is so common as to be a taken-for-granted aspect of political life that rarely raises an eyebrow. In some cases, such as North Korea and Syria, the entire state is inherited. Participants in my focus groups pointed to the pervasive and largely unchallenged rules of the game that allow this to occur globally and discussed the ways in which it prevents political reform in many places – not just in governments but in international institutions as well. An anti-corruption agenda for the 21st century should include some focused attention to this problem.

11) International Voting Rights. The international community likes to talk about democracy promotion, but this is normally couched in terms of creating accountable, transparent and inclusive institutions at the state level. Not much attention has been given to democratizing political processes at the global level. Some practitioners argue that more attention might be given to inclusiveness within global institutions, or international voting rights on key issues that affect not only states but also individuals. A recent book by OXFAM’s Didier Jacobs lays out this argument more forcefully and shows how it could be institutionalized.

12) Impunity for Death by Neglect. As of 2005, the International Criminal Court can try and punish individuals found guilty of crimes against humanity including murder, rape and forced displacement. But governments enjoy impunity for deaths worldwide that result from benign neglect of their citizens, rather than intentional atrocity. Half a million women die due to pregnancy or childbirth and 11 million children under five die from preventable diseases each year, not because any leader wished it but simply because resources are channeled to palaces instead of hospitals, to militaries instead of health clinics. As we move into the second decade of the 21st century, those on the front lines of the human security community argue for a more expansive notion of impunity, and new mechanisms to incentivize leaders to create a fairer, safer world for all.

Question to readers: what issues do you feel should receive greater attention by human security advocates in the coming decade?

*(For more on how this graph was generated see this post.)

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

0 Comments