[Updated]

No sooner do I pen an intemperate, semi-coherent rant about the culture of pretending-to-know-things among graduate students, then Nawal Mustafa makes a probing comment:

From the student side of things Dan, it strikes me as a deeper problem that transcends the academy. Certainly, I concur students should take responsibility to ensure they are actually learning, and not view their seminars as merely an exercise in impressing others, or securing great letters of recommendation by purporting to “know” the material. That said, there is a deeper problem where success and achievement, even from a student’s early years, is equated with perfectionism, control, risk-aversion, and there is a genuine fear of making mistakes in the process of learning. Students are encouraged to be safe and risk-averse thinkers because that provides better pay-offs. I’ve referred others to Sir Ken Robinson’s rather infamous lecture on the matter: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iG9CE55wbtY.

As Robinson notes, “What we do know is that if you are not prepared to be wrong, you won’t come up with anything original.”Our schools are not teaching students to embrace this, but actively encourage them to avoid it. Whether it be the K-12 system, or the university, dissent is disciplined, conformity rather than creativity is the order of the day, and the academy is no different.

In my own graduate seminars, I’ve observed students who hesitate to question a professor’s particular standpoint because “that’s too much effort,” or he/she “won’t listen to what I have to say anyways.” Whether that assessment is correct or not, the point is there is a general pressure to conform and take the “safe” route. Students then write essays that they think are more agreeable rather than contrary, and refrain from providing their authentic, creative voice on exams given the fear that this will jeopardize their academic track record, unless they luck out and happen to have professors who agree with them. Sure, there needs to be standards, but true dissent, the willingness to take a gamble and be “wrong” is disciplined out, from an early age and especially at a more advanced level.

The other problem is incentives. If students have a negative experience where one professor does not encourage such creative, dissident thinking, it will likely not matter if they have other teachers who do so. The challenge at the PhD/graduate level is twofold: how to encourage graduate students to retain their sense of self, their creativity, and yet recognize the process of gradual professional socialization which does take place, and there are obvious tensions that exist between those two objectives, and secondly, how to encourage professors/advisors to still foster creative voices, while trying to steer their students professionally, which entails making them aware of the academic politics and unfortunate practical aspects involved in the profession. The general problem is that even scholars themselves struggle to embrace being “wrong” and attempting to be creative in an environment which often hinders such dissent. Not to say being creative entails making mistakes, but I contend originality is not necessarily possible without the latter.

I understand the temptation not to admit ignorance –especially when everyone around you refuses to admit ignorance. This is a pretty straightforward pareto-inefficient outcome, albeit one rooted in a mistaken understanding of the payoff structure of the “seminar game.” The unwillingness to challenge professors, on the other hand, befuddles me. It never occurred to me not to let my professors know when I disagreed with them; I went to graduate school with a number of people who had the same attitude, including PTJ. I’m pretty sure that we all learned a great deal more through the resulting, sometimes agonistic, discussions.

I have heard stories about senior professors complaining about a growing culture of conformity among graduate students. I had my pet theories about the causes, but if it (1) isn’t getting worse and (2) plagues British academia, then I’ll probably have to discard some of them them. At the same time, the fact that this culture doesn’t operate everywhere — it certainly wasn’t the case at Columbia in the 1990s, and I know of at least two major programs in the United States where the graduate-student culture is closer to my ideal — suggests that professors can successfully foster a culture of respectful intellectual contention.

One thing I’m not convinced by is the “one bad apple” argument. I know that some students will overgeneralize, but my sense is that even at places with a culture of conformity graduate students are savvy enough to distinguish between professors who like being challenged and those who don’t. Of course, there’s a secondary level to this, which we might think of in terms of a “range of tolerance.” Some professors are terrific about fostering a creative atmosphere, but only within a very circumscribed understanding of proper inquiry. Others are less effective, in part because they admit a broader range of perspectives into the classroom. The question is: how to combine the two.

Thoughts?

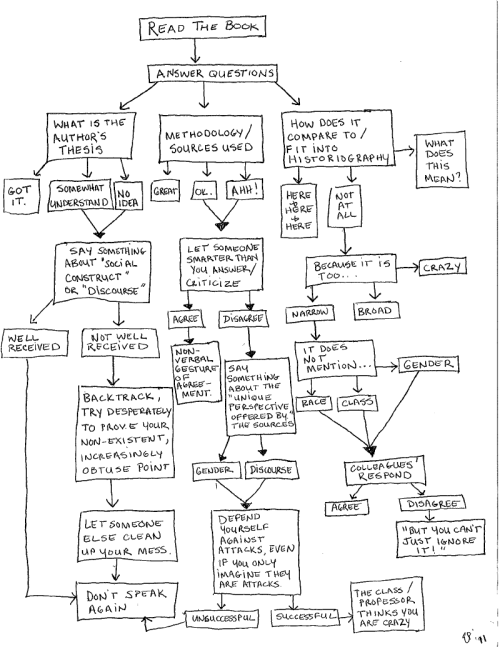

UPDATE: Courtesy of Becky S., Erin Feichtenger’s “Grad School Explained” Chart:

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Dear Dan,

I think the case of conformity in class has all to do with the person teaching and the institution’s learning culture. In the three years I have spent at my University I have been constantly asked to challenge my teachers and peers opinions’, without ever compromising knowledge or excellence. I think the important thing is to make students comfortable with contestation, make them feel like that is the road to new knowledge, without compromising other aspects of learning.

A non-conformed student

I just realised this was directed solely at graduate school and not universities in general. I guess I will have a taste of that next year.

One quick note of clarification Dan, esp. given that I’m mentioning this in light of a British educational setting, and one known for its intellectual pluralism. To be honest, some of my best teachers have been in this setting, and I consider myself one person who has tried to be agonistic, challenging, critical, and for that reason, have found the experience/seminars greatly rewarding. My skepticism–especially in regards to power/knowledge relationships–in those comments derives from my observations of my peers. Even in this relatively open setting, I still find graduate students are hesitant to be creative, self-censor their comments if you will, and you are indeed right to point out the politics involved. Even in the relatively open, graduate institution I’m at, which is likely far more open than many U.S. programs theoretically and philosophically, part of surviving graduate school I find, unfortunately, is learning which professors are open, which ones aren’t, and which ones will truly allow you to have that creative voice, and strike that balance. For educators and students alike, it is no easy task. Either way, I tend to be a sharp critic, pondering if the system as a whole still thrives on conformity versus creativity, or if the academic profession writ large has not struck that balance well either…

The best distillation of this phenomenon, which was assigned in a class to help prevent it, is this.

https://www.salon.com/life/feature/1999/02/16feature2.html

I sometime mutter to myself “How is Smurf’s work going? I understand he’s had some remarkable findings” when I hear people signaling how smart they are as opposed to actually discussing ideas.

I can’t speak to graduate experiences elsewhere–in the closeknit world of our cohort, I’ve always felt free to challenge, though with some professors it has been necessary to develop a fairly specific vocabulary and diplomatic skill for doing so while preserving the relationship. But in other learning contexts–skills institutes in my own dear peacebuilding program come to mind–I feel the pressure to conform often comes less from the instructor and more from the participants. When most people (or the most visible people) are emotionally invested in a worldview shared by the instructor it creates this sort of oppressive culture of inoffensiveness that made me feel hesitant to name myself the enemy when others seem to be vigorously buying in to a lecture I thought was bunk. Perhaps these are contexts in which we assume total overlap between our ideas, our feelings, our experiences, and our very selves, in which challenging a leader of the group becomes a challenge to other group members on a personal rather than intellectual level. Maybe it is just the extent to which universities or particular programs are politically or ideologically aligned, and students who feel like they are the odd man out are posing a challenge on a much deeper level than simply having a contradictory idea, they are challenging their belonging in a bigger community.

Don’t get me wrong, I think it is crucial that classrooms be a place where people feel safe and respected. But I can think of multiple instances when I’ve seen that actualized not as the creation of a safe space for the free exchange of ideas but as a place in which certain ideas, and sometimes any form of objection, are tacitly assumed to be unsafe and challenging to the emotional investment others have in the starting viewpoint, and thus excluding them is the means of preserving the safe space. Or perhaps the explanation for this social enforcement of conformity is simpler: for those for whom the purpose of the course is the dissemination of information, challenge and argument are a distraction and a disruption that is keeping them from their end goal–completing a credential, taking down the insight of someone they have accepted as an authority, whatever it may be.

Regardless, I find that when this sort of “oppressive inoffensiveness” sets in and the group as a whole seems to ward off challenge preemptively, a few good acts of resistance will either break the spell for everyone–in the hands of a good instructor–or turn the group on the challenger to silence them when leadership is less apt.

Or, perhaps we have simply blurred the line between demonstrating understanding of material and accepting its conclusions when we grade students, and they have learned that the latter is the safer course for their short term aims, or at least that it is easier to fake it.

Haven’t read the comments but have read this post (and the preceding). My experience is prob. atypical b/c: (1) i went to a ‘non-major’ program; (2) started at an advanced age after having had another ‘career’; (3) didn’t get an academic job when i finally finished (perhaps that’s not so atypical). That said, in only one of the PhD seminars i took can i recall something like a ‘culture of conformity’ being a problem. And in that case it was mainly the prof’s fault, as he was someone who really cared about getting us to see the world his way (i read that as dogmatism though i think not everyone did). In other seminars i took, ‘faking it’ and conformity were not the main problems. There were problems from time to time, but they were other sorts of problems.

I think Dan N.’s complaints would be both more interesting and convincing if he gave examples of, e.g., the “frakking stupid” things that get passed from generation to generation via timidity about asking questions. Also, there’s a simple solution as far as his own seminars are concerned: just read these posts to the students on the first day, and then say: “Moral: don’t fake it. Ask questions if you don’t know something. I’ll actually respect you more if you do, and still write a recommendation for you, etc.”

Problem solved. That will be $10,000 for 10 mins of my consulting time. Drop it off in small bills in Rock Creek Park at a location that i will specify. :-)

Stuff that’s “frakking stupid” includes understandings of: Waltz (although things have improved in the last 5-6 years); “Constructivism” in some non-Constructivist circles; stuff we’re finally waking up to viz. what p > .05 actually means; the term “structure”; etc.

I’d like to second the constructivism thing. In my interactions with grad students from top-ten programs I have been genuinely surprised at their sheer ignorance of the point and substance of constructivism in IR. Three particularly egregious examples are a student who said, “yes, everything is socially constructed. But you have to move past that to explain anything”, another who said, “err, it’s about how things are co-constituted, or something”, and possibly the worst, “If anyone ever does anything that is not in line with a norm, the norm doesn’t exist”. Actually that last one was James Morrow at APSA 2008.

Just to balance it out a little, the fact that people make mistakes or have ideas doesn’t mean that game theoretic or public choice models aren’t extremely useful in a wide variety of situations.

I’d also add a large chunk of what people say about scientific progress and the philosophy of science….

This knowledge of constructivism is really quite upsetting…I’m at the final year of an IR undergrad course in the UK and I am pretty sure my class all has a much broader/deeper knowledge of the material…

Dan, could you provide a cite on the p > .05 thing?

Here’s two:Andrew Gelman and Hal Stern:https://www.stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/research/unpublished/signifrev.pdfMcCloskey and Ziliak:https://www.amazon.com/Cult-Statistical-Significance-Economics-Cognition/dp/0472050079

Dan, I know (for a fact) that many grad students intentionally self-censor for careerist reasons. (And no I’m not singling out my department here; it seems to be a common experience.) It’s not uncommon to hear a grad student say things like “It’s important to me for this person to write me a strong letter when I’m on the job market, so I don’t want to antagonize them.” And those signals aren’t made up by paranoid students… it’s instilled pretty early on that a big part of grad school success is cultivating close relationships with professors, and some professors send fairly strong signals that they’d prefer students that continue their own research programs rather than do something new, or otherwise value pliability over other qualities.

Additionally, some professors seem to either not have a clear sense of how politics works outside of their specific area of expertise, or have no special proclivity for sharing it. I’ve had classes and seminars with professors where, at the end of the semester, I really don’t know what their views are. I’m not sure if this is an intentional decision to “teach the material” or something else, but in that environment it’s difficult to be challenging because there’s not much of anything to challenge. And there are many grad students that seem to value “learning the material” over challenging it or their fellow students, much less their professors.

I have no idea whether this dynamic is more prevalent in American rather than European schools. I suspect it isn’t, but rather manifests itself differently, given paradigmatic differences.

I also don’t know how much of it has to do with pride; my experience is limited, but both grad students and professors that I’ve had a lot of exposure to seem to have no problem admitting their limitations, especially outside of their specific area of expertise. In fact the opposite may be true: it’s tough to challenge something if you have an awareness of your limitations. Many professors are deferential to their students (esp the more advanced students) in discussion where the student has greater substantive (or methodological) experience than the professor.

And not all professors (or grad students) are this way, of course. I’m not even sure if it’s the modal experience.

“some professors send fairly strong signals that they’d prefer students that continue their own research programs rather than do something new, or otherwise value pliability over other qualities.”

Yeah, I suppose this just doesn’t make sense to me. I’m really uncomfortable with the idea of my graduate students extending my own agenda, although I recognize doing so would be a very good “career move.” Even if I did, I’d want them to challenge me.

My problem with “learning the material” isn’t that this shouldn’t be a key goal — I just don’t think students learn that material as well if they don’t wrestle with it, and that wrestling with it requires engagement with peers and professors.

I’m glad that you’re experience has been pretty good. I wonder, though, how widespread that is. It does feel to me that graduate students are, overall, more careerist than they used to be. In part, that’s a defense mechanism to lousy job prospects. But I wonder if it isn’t also a product of having very settled, straightforward career trajectories, i.e., of the field’s increasing methodological closure.

p.s. Your last paragraph suggests there is a tension between fostering a creative atmosphere of inquiry and admitting a broad range of perspectives into the classroom. I don’t think there necessarily is. I think the prof cd put his/her cards on the table and say ‘look, my perspective is XYZ. But my goal in this class is not to convince you that i’m right but to try to subject a variety of perspectives to critical scrutiny in as evenhanded a way as possible, subject to the inevitable limits of human frailty/fallibility etc.”

W/ all due respect, i don’t really think this is that difficult. However, i’ve never taught a grad seminar so i could be wrong.

I think some people pull it off, but I suspect that there is a tension. If everyone has clear and shared standards of evaluation it becomes easier to have focused, critical discussions. Or is that wrong?

I see. Yes, this perhaps could be an issue if people in the seminar approach things from different methodological standpoints, hence have different standards of evaluation.

I was just thinking of the first-year PhD seminar in ‘contemporary IR theory’ that I took a long time ago. I think that particular prof managed to negotiate the tension quite well, but perhaps it’s easier to do in some kinds of seminars than others. (Low battery, have to stop here.)

Given the hyper-political environment of graduate school (and academia in general), it isn’t a surprise that most graduate students view grad school as just a series of hoops they must jump through to graduate. I know that is how many of us feel. A lot of us are pretty hard headed when it comes to “sense of self”, but we save our real self for therapeutic gripe sessions outside of the walls of campus.

We assume, often falsely, that we will have more creative freedom once we land a job. How short-sighted and naive of us.

In what sense do you mean “hyper-political”? Genuine query — there are lots of possible answers.

I’m referring to office politics between professors, students, and the combination of the two.