I was recently asked whether

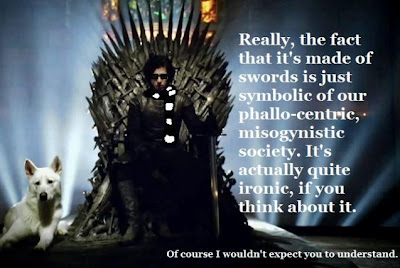

Game of Thrones was going to become “the cult IR series of 2011.” My initial response, spouted on a FB update was, “it remains to be seen,” not least since by next Spring GoT will of course be competing with

Blood and Chrome.)

As of today, however, “seen” it has clearly been, with multiple IR bloggers posting on various “IRGoT” themes. So I guess that answers that. We can look forward to a veritable bevy of GoT-blogging among IR types for the foreseeable future.

OK, let’s see, Steve

suspects the show can best be viewed through the lens of cognitive psychology, and Dan

thinks it demonstrates the timeless wisdom of realism. Pablo K, however, in a

remarkable, wide-ranging piece at

The Disorder of Things takes a more critical view, interrogating gender and racial imagery in Season One with all the tenderness of Gregor Clegane:

The most common female figure is that of the whore; the most common male one a loyal killer. Physically weak, generically meek, hopelessly devoted to their menfolk, the women of Westeros cower and sob at violence and prove useless at the calculations of politics. Catelyn Stark provokes outright war by bowing to her maternal urges and kidnapping Tyrion Lannister on slim evidence that he tried to kill her son, a decision unlikely to have been endorsed had she consulted with her husband, notorious as he is for bad decisions. Cersei Lannister, as Queen of the realm, fares better, managing to manoeuvre her son onto the throne, at which point he becomes a power-mad sociopath, forcing Tywin Lannister to send his own imp son to the capital to pick up the pieces and rule from behind the scenes. Which leaves Arya Stark, everyone’s favourite tomboy, protected from the solid binaries of Man and Woman by the relatively ungendered space of girlness. Thin and still flat-chested, she is able to pass, Shakespeare-like, as a boy. For now.

Married off to Drogo as the bargaining chip for his army, Daenerys Targaryen becomes the sock-poppet for a Game Of Thrones version of feminism… In a parody of anti-rape politics, it requires the authority of this high-born Queen to prevent the conquering Dothraki army from sexually violating the wives, mothers and daughters of the conquered… Wilful in spite of her relative fragility, Daenerys derives her determination from the male heir inside her… empowered by protective feminine impulses over her precious boy cargo, she transcends the pliant object we first encounter to become a commander of men, but only so long as she can claim to speak for their true Lord (wait until I tell Drogo about this!)

Burn! [Sorry…] Seriously, read the whole thing. The discussion of the heavily racialized Dothraki is pretty spot-on – “like Klingons without technology. Oh, and they’re quite swarthy.” The comments thread is also to be studied closely.

I do however see a few things differently from Pablo in terms of gender. I may develop a longer and more coherent essay on feminisms in GoT in due course (this one was drafted at 2am), but here are four initial thoughts:

1) Any discussion of gender in GoT needs to closely examine men as well as women. (To give only the most obvious example, the institution of bastardism is as fundamental to social relations in the show as are male/female hierarchies.) And let’s not exaggerate: the most common male character is not a “loyal killer,” it is (probably) a conflicted witness to killing. Of course there are loyal killers aplenty, but even more disloyal killers plus all manner of men and boys trying to avoid the profession: spies, cravens, eunuchs, squires, metal-smiths, clerks, and capitalists. And the male characters with whom we are most allowed to identify are those who embody an ambivalence toward violence and aim to wield it, if at all, justly. (That Martin means it this way is evident from the way he organizes his book chapters.) There is more complexity here than meets the eye.

2) The most common female character is certainly not the whore (Ros, Shae). It is the political figure – queens (Cersei, Daenerys), ladies of the realm (Catelyn, Lysa), or princesses (Sansa, Arya). But more importantly, it is simplistic to suggest that the female characters all follow any single gender archetype – different “ladies” do different things with their status and power, and even the “whores” are multi-dimensional. I see tremendous and fascinating variation in the way women are portrayed and their connections to gender and politics generally in their societies.

3) Pedagogically, one can usefully distinguish strong women from feminist characters in the show, and also different

models of feminism with which Martin toys: i.e., there is not “

a Game of Thrones version of feminism” but rather different representations of different feminisms that have analogues in global politics. First, there are many

strong, smart women here – I certainly count Cersei and Catelyn among them, if not Sansa and Lysa – but this doesn’t necessarily make them feminist characters (in my view) since their frame of reference has nothing to do with overturning gender hierarchies. Arya, however, does embody a

liberal feminist discourse: she insists on the right to take on ‘male’ roles but resists denying her own sex in order to do so. “Passing as a boy” is not her modus operandi but rather a strategy imposed on her, an eventual, temporary nod to traditional norms in a desperate bid for survival.

4) Consider Daenerys by comparison. I

continue to disagree that Dany’s character simply reflects and reifies patriarchal norms. She does

not, first of all, derive her determination from her male fetus, but rather from the friendship and mentorship of women who surround her (especially her handmaiden and later, at least for a time, a female priestess/healer), as well as the respect of powerful men (she has no time for those who disrespect her – her brother, Drogo’s men, duplicitous merchants).

True, it’s vital to interrogate what peculiar kind of gender ideology she represents. I would argue that Dany, in contrast both with Arya’s rejection of conventional gender norms and Cersei/Catelyn’s indifference to them, represents, for want of a more appropriate term, “

state feminism” – her strategy is to accept and embody patriarchal gender archetypes long enough to achieve insider credibility. She then uses the formal power this gives her to engage tribal governors in the service of feminist ends, seeking common cause with other women across clan boundaries and attempting to alter the violent gender norms of her new society marginally in their favor, without questioning its foundations. But her embedded position within a violent, gendered governance structure means she can take this agenda only so far. Ultimately, Dany fails to question, empathize and comprehend the perspective of women with a different standpoint, so her best intentions turn on her and on the objects of her pity. Hers turns out to be the neo-colonial feminism of the white northerner

bent on rescuing the oppressed (and in so doing obfuscating her society’s

brutality to its ‘own women) rather than seeking to understand them. Failing in this effort this she turns oppressor to reconsolidate her own power base against the “other.”

Is this a patriarchy-affirming narrative? Certainly it is a narrative of patriarchy, illustrating its capacity to divide women against themselves despite their best intentions. But it is also a story of female agency and of identities that cut across and transcend sex and gender. The Maegi’s death represents the post-colonial feminist lesson about the limits of state/colonial feminism. We are meant to be sickened and shamed by it, and to be reminded that neither women nor feminism should be equated with nonviolence. The denouement of this chapter in Dothraki history should not be interpreted itself as being blindly orientalist or patriarchal but as tragically illustrative of the promise and pitfall of different feminist strategies.

Now, Pablo K would (I think) respond as follows:…

fiction is an important stage for tropes of war, diplomacy, sex and race, not least because we’re freed to engage in a more fulsome emotional investment precisely because it’s not real. Excepting professional researchers, activists and inveterate news addicts, the time spent with such representations outstrips that devoted to engaging them in the realm of contemporary politics.

Maybe. However since I’m thinking about this series primarily as a pedagogical tool, I hope I can be forgiven for thinking the series is – or can be understood as – more subversive than it means to appear. Thoughts?

*Though in fairness, the HBO version of Dany and Drogo’s first ride is very different than the book version.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

There’s absolutely loads to say about this, and lots of exciting geek argument to be had. I’ll do my best to be brief:

1. Absolutely the masculine hierarchies matter (maybe another post on those). I’ll only note here that feminist analysis has lots to say about the setting of males in relation to each other and the exclusion of bastards and eunuchs is compatible with that (either because they lack the proper seal of male authority or because they are feminised). A clarification on ‘common figures’: I don’t mean the central *characters*, who become interesting to us in relation to more general actors (sometimes following GoT world norms, sometimes not). But I don’t quite mean the sum total of background characters either. I mean people seen as carrying out actions in the series and as given some kind of named role (whether as a collective or individuals). So when nameless groups of armed men pledge allegiance to Robb or turn their pikes on Ned on the orders of Baelish/the Queen, I regard these as common figures of the loyal killer (warrior is perhaps better). People standing around at an execution wouldn’t count. I stand by that!

2. Ditto, I include here the various wenches we see running around the Baelish establishment, the pubs, etc. Certainly they are more numerous than Queens. And I don’t think the female characters follow a single gender stereotype. In any case, patriarchal emplotment is perfectly capable of having female/feminine characters occupy a range of roles. The question is how these roles are organising in relation to each other and to the male/masculine roles. So the possibility of Queens does not lessen the patriarchal tenor, since they are at best the plotters, representatives and emotional support for Kings. Which is the crucial things about Dany, whose ‘political’ status rather disappears when her man passes on to death-but-not-death. There is only one *ruling* Queen in Game Of Thrones (I think): Lysa Arryn. And she is, as we say, batshit crazy. There is indeed variation that is fascinating, although I don’t really think it can be called tremendous in scope. I fail to see how it differs from the variation in female gender roles that obtained in medieval societies. Certainly there would seem to be less capacity for female agency (and choices) than in a show set in contemporary America or Britain. Consider that in GoT there are no female warriors, no female advisers and intellectuals (only behind-the-scenes plotters), no female traders and no female ambassadors. There are queens, princesses, ladies, whores, nannies, witches, one tomboy and one barbarian-tramp-turned-nanny. Looks like a standard roll-call of female roles in a masculinist imaginary, unless we are going to claim that the Kingly courts of Tudor Britain don’t count as patriarchal because there were women there with some kind of status and autonomy.

3. Again, I don’t think that the mere occurrence of smart and strong women constitutes a progressive or feminist standpoint. I agree that things are so bad, entertainment wise, that it’s notable how many female characters there are in GoT. But that’s setting the bar pretty low (I’m not sure, for example, that GoT would even pass the Bechdel Test). *How* are they smart and strong? Overwhelmingly they’re smart in the sense of having cunning and a desire to advance the position of their men (whether that’s husbands or sons). But not that smart. Cersei is the only one who can be read as ‘succeeding’ or making acute tactical choices, and then she quickly loses control of the situation once Joffrey actually takes the throne (although I expect there to be further machinations on this point ahead). And they’re strong in the sense that they take beatings and/or show determination in their support of men doing things (like going to war to avenge their fathers).

3a) As for Arya, she can be read in liberal feminist terms (and in more radical ones too), but I think her youth complicates things. She does not ‘resist’ being called a boy because society is trying to impose those norms on her. Instead, she is repeatedly *mistaken* for a boy, in part because she likes exploring and fighting, but also in part because she is young enough that she remains ambiguous to the male gaze. Again, I think this is totally compatible with a patriarchal reading, since girls are often allowed to be tomboys until they enter the sphere of womanhood, at which point a different set of norms and expectations apply. The ‘test’ of Arya’s relationship with feminism will be how she negotiates her role once it comes time to marry her off as political currency.

4) Dany’s ‘friends’ are a good illustration of some of the above points. One, a white sex-slave given to her by her brother, mentors Dany in how better to seduce and pleasure Khal Drogo. Leaving aside the extent to which a Queen and a sex-slave could be taken to be meaningful friends, her role in the series is to enable Dany to take a more autonomous and political role via the use of her sexuality, which is what we might call a rather ‘problematic’ form of feminine empowerment. We see little of Doreah after that. The ingrate witch Mirri Maz Duur hardly seems to qualify as ‘friend’. She works her ways into Danys affections, poisons her husband (it was her ‘treatment’ that made the superficial cut on his chest into a death wound) and then strikes a blood bargain in which Dany loses both Khal Drogo and her son, as well as the ‘respect’ of the men who only obeyed her whole Drogo was alive. Drogo seems to love her, in his barbarian way, but she only gains the respect/fear of Ser Jorah Mormont when it comes to the dragons (i.e. when she transcends normal humanity). Up until then he protects her in a standard masculine role of loyal warrior (see!), but is also the person who informs King Robert that Dany is pregnant and so triggers attempts on her life.

OK, so that wasn’t so brief. People may well take gender-subversive ideas from the series, and I think it is in the nature of any aesthetic or representational object that this will be a possibility. I just very much doubt that that’s the primary gender/race message available for our identifications.

“I fail to see how it differs from the variation in

female gender roles that obtained in medieval societies. Certainly there would

seem to be less capacity for female agency (and choices) than in a show set in

contemporary America or Britain. Consider that in GoT there are no female

warriors, no female advisers and intellectuals (only behind-the-scenes

plotters), no female traders and no female ambassadors. There are queens,

princesses, ladies, whores, nannies, witches, one tomboy and one barbarian-tramp-turned-nanny.”

I agree there. That was my disappointment with the series.

On one level, if it aims artistically to illustrate patriarchal norms and how

women attempt to exert agency in multifarious (but limited) ways, then it

somewhat succeeds in that regard. I suppose if it was meant to be a

historical piece documenting medieval norms and practices, I would be less

critical. Given, however, that it fits fantasy as a genre, it begs the question as to how

many works in this vein actually A) grant women agency which transcends

gendered binaries, hierarchies, discourses and practices, and B) challenge such

matters beyond the level of the women themselves. I wouldn’t consider the

series subversive in the latter respect given that it’s ridden with gendered language

throughout–the masculine subject at war, home, and otherwise, is constantly

constituted through the feminine other, and that is never really challenged at

a deeper level in the series. Violence itself, as productive of masculinities and femininities, and as a product thereof is not fully interrogated. Moreover, by focusing specifically on the women as agents, we again fall into the trap of analyzing sexuality as opposed to broader gendered issues at stake in popular culture. In all those respects, the show like many others falls short for me.

Then again, even in Lord of the Rings, to my knowledge, the

film producers and screenwriters had to give women more lines and visibility

given that they were quite absent (or so it seems) from Tolkien’s account. It

would be fantastic and truly subversive if women in the fantasy genre not only

occupied more versatile political roles, but also if the writers found a way to

not only elucidate, but also demonstrate a transcendence of such binaries and

gendered discourses. Sure, GOT is excellent entertainment, but I wonder if that

has to do with an exotic depiction of times we utilize to constitute the modern

subject, in a sense reaffirming notions of science, progress, and I daresay

liberal understandings of female empowerment. If anything, to me, it does not

create a compelling alternative space, but merely perpetuates (perhaps unwittingly)

linear narratives of space, identity, and time as conceived in popular works of fiction. We, as viewers, can be

entertained by examining practices we associate with a premodern, barbaric,

brutish, and gruesome other, a sober reminder of how far we have come?

One more thing: Discus for some reason reformatted those comments in an odd way, please excuse the spacing and whatnot.

I think both of you have a point, and probably one of the reasons I see more depth to the female characters is because I’ve read the book. There actually are female business-owners (for example the owner of the Inn where Catelyn takes Tyrion); and there are female warriors (they haven’t showed up yet). It is true that if I’m comparing the series to the book rather than comparing my interpretation of it to Pablo K’s interpretation, I’d agree that the series comes off as less gender-subversive than the books – actually it was the very first thing I noticed in the first episode, and wrote about here:

https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2011/05/thrones-and-cronesThat Lord of the Rings was the exact reverse is very interesting.

I’m actually surprised that economic determinism hasn’t even been mentioned in these discussions. Take for example the Night Watch that goes a step further than the traditional US military recruiting tactics of targeting the poor to supply its forces. It enlists those convicted of criminal offenses although during the Stop-Loss policy period, the standards for recruitment were lessened as well by some recruiters. In any case, they perform the most dangerous tasks and are held at a higher standard than its leaders for very little pay.

The closing sequence is that of Daenerys emerging from the bonfire with 3 newborn dragons. Her “army” is a collection of ex-slaves that now will presumably benefit from the impact of these new weapons of war. What a game-changer! A poor country now with dragon-capabilities? That’s right, Daenerys Targaryen has her nukes!

Specific discussions of gender necessarily need to be examined through economic determinism as well. The aristocratic status of Daenaerys means little initially as she’s treated like chattel but Cersei Lannister is able to exercise her power as a result of both her status and fortune.

When Jorah Mormont suggests to Daenaerys to sell the dragon eggs, she wisely decides against it. Her baby nukes should yield a greater fortune in the long run.

Dr. Charli is right. If you have read the series, there’s more depth to the female characters and less pseudo – racism ( what? white characters look admirable in this book? What planet do these ppl reside on?) than the IR blogosphere sees.

Happy to take your word for it but I, at least, was discussing the HBO series and made clear that I hadn’t read the book. I do understand the fidelity reaction (‘but the books are different!’), but it doesn’t seem to me to add up to that much of a counter-critique. Obviously there’s a link between the book and the series but they’re also different kinds of cultural object and are consumed by different (if perhaps significantly overlapping) audiences. I don’t think analysis of Fincher’s ‘Fight Club’ should be dismissed on the basis that people haven’t read Palahniuk, although there are import differences between the two versions. Of course, if people are trying to criticise the books on the basis of the series, then a rather significant problem arises, but I don’t see any evidence of that happening here.

I’ll humbly admit Zen to not having read the books either, and Charli and you both raise fair points–perhaps they are more gender subversive than the HBO series. That said, I also agree with Pablo’s comments below as well–to me, referring to the text is not a sufficient counter-argument given that they’re two different mediums, different power relationships are involved in the production of both, and the audiences are different. The interesting question pertains to how nonverbal visualizations, images, and performances also perpetuate gendered hierarchies and binaries to a greater degree in the TV series, which obviously has that visual component, as opposed to the text, which realistically can only capture that verbally to a certain degree. It also begs the question as to why and how popular media then reinterprets texts in a manner that still advances (perhaps to a greater degree) gendered discourses, images, norms, and ultimately, patriarchal binaries and narratives. What is the rationale behind this? What does this tell us about our society (did the HBO producers presume more sexual objectification will have broader commercial appeal?) To me, given the broader audience with the series as opposed to the text, it highlights the power relationships involved in media production in particular, and so forth, a separate issue that is avoided by simply referring to the texts. Either way, my comments below for that reason pertain to the series as a focal point.

GOOOOOOOOOOOOOOD Job~~~Thanks for this good article. Excuse me go read it. Hopefully more success. by fifacoinvip.co fifa coins