Co-authored with Alison Howell, author of Madness in International Relations: Psychology, Security and the Global Governance of Mental Health

Co-authored with Alison Howell, author of Madness in International Relations: Psychology, Security and the Global Governance of Mental Health

The recent events in Norway have revealed the pitfalls of speculation within a 24-hour new cycle/instant social media environment. Almost immediately after information about the bombings and the shootings emerged, facebook, twitter, and media outlets were saturated with possible theories on the source of the violence- with most of the speculation focused on radical Islam and Al-Qaeda (The Atlantic immediately re-posted a great article on Al Qaeda in Norway).

In the ensuing days, a new kind of speculation has become common in reporting on these events: that is, speculation about the psychology of the man who admits to committing these acts (if not his guilt).

Much of this started with Breivik’s own attorney vowing that his client must be insane and that he would only continue to represent him on the condition that he submits to psychological testing. But a number of news outlets, and indeed psychiatrists and psychologists interviewed in the media, have decided not to wait for these kinds of assessments, preferring instead to speculate about Breivik’s psyche based on the very limited information that we now have.

One particularly troubling example of this kind of psychiatric speculation includes a July 25 BBC Europe article, which asserts that “a deep level of mental disturbance” underlies Breivik’s motivations. The article quotes a professor of forensic psychiatry stating: “The bottom line is that we don’t at this moment know enough about his motives to diagnose his mental state. However, while there are all sorts of cross-cutting with right-wing ideology, I believe he is likely to be suffering from a mental disorder.” The article then goes on, to compare Breivik to David Copeland (the 1999 London ‘Nail Bomber’), citing the same professor as saying that “The Norway attack is on the same lines – where extreme right-wing beliefs merge with paranoid psychosis, or delusional disorder….”

The article also quotes a forensic clinical psychologist, who, based on Breivik’s ‘manifesto’ is willing to authoritatively avow that Breivik must have been a ‘shut away,’ ‘insane’ and ‘deluded.’ These kinds of highly speculative pseudo-diagnosis are not confined solely to the BBC report: the Telegraph described Breivik as a “blond psychopath;” another source wonders if Breivik is insane or just evil; and Time magazine has recently published a piece in Breivik entitled “An Interview with a Madman.

Similarly, West Side Republicans– a Republican blog recently sported the headline “NORWAY – Breivik is a politically isolated sociopath. Not A Christian Fundamentalist as the Media & Left would have you believe.” The main conclusion of the post is that “Breivik’s murder spree did not result from classical liberal influences any more than it resulted from Christian influences: It resulted from his own evil and twisted mind.” The blog also takes issue with the way that the New York Times has portrayed Breivik as a Christian extremist, claiming: “The problem is this: There is no “Christian extremist” movement in the way that there is an Islamist or “Islamic extremist” movement. There are bad Christians, to be sure; but they have no modern-day intellectual and political movement that supports and sustains them — modern-day Islamists, or Islamic extremists, do…”

This kind of psychological speculation evident here is highly dangerous, for at least 3 reasons.

1. The idea that he was a solitary monster ignores clear evidence of a wider political community sharing his ideals. We now know that Breivik sent his manifesto out to over 250 individuals just before the bombs in Oslo were detonated, including several far right politicians and the anti-Islamic English Defence League (EDL). It was reported in the Foreigner that “several supporters of the EDL admitted they met Breivik at rallies in Britain and the attacker even confessed he had over 600 EDL members among his Facebook contacts.” Even Breivik’s lawyer has stated that Breivik is part of a wider community of right wing fundamentalists- referencing two additional cells in Norway. Breivik was also a prolific contributor to right wing blogs, and pointed to extreme right wing political parties such as Germany’s far-right National Democratic Party, and the Netherlands’ Freedom Party as sources of inspiration.

It isn’t the thought of Breivik as an isolated monster that is disturbing, rather it is the realization that he has is part of a broad community that share his ideals- if not his tactics. Just Wednesday a member of France’s far-right Front National was suspended for referring to Breivik as an “icon” and a “defender of the West.” Even more disturbing were comments made by a faction of the Europe of Freedom and Democracy group in the European Parliament: “One hundred per cent of Breivik’s ideas are good, in some cases extremely good. The positions of Breivik reflect the views of those movements across Europe which are winning elections.”

2. This kind of psychological speculation perpetuates the pervasive myth that violence is a characteristic of madness, when in fact people diagnosed with mental disorders are no more likely to commit violent crimes than those who are considered sane. It’s no surprise that the two experts called on in the BBC report mentioned above include a forensic psychologist and a forensic psychiatrist: these are highly problematic disciplines dedicated to tying together crime and madness. It is time, once and for all, to dispel this myth (which is particularly attached to people diagnosed with schizophrenia). Like the term ‘queer,’ the term ‘madness’ is increasingly being reclaimed by organizations such as MindFreedom International and activists in the Mad Pride and psychiatric survivor movements, who are working to claim their rights against often coercive systems of mental health governance. Casting violent acts as evidence of insanity makes it more difficult for such activists to get us to see that madness is just another form of difference (like race, gender or sexuality), and that mental health should be understood in terms of social justice.

3. Psychological speculation renders Breivik’s motivations exceptional and irrational, rather than placing them in the broader context of political debates — especially as they concern multiculturalism in Norway, Europe, or more broadly the West. Regardless of Breivik’s mental state, we should listen to what he lists as his motivations and view his actions primarily as a form of violence motivated by racism. If we pay attention to the way that right wing media outlets are spinning this story it becomes apparent that the underlying anti-immigrant racist ideals of Breivik have traction across the globe. The highlights (or low-lights) of Pat Buchanan’s insights into the attacks in Norway Breivik shows a defiant and impassioned defence of the motivations expressed by Breivik:

“Though Breivik is being called insane, that is the wrong word….Breivik is evil – a cold-blooded, calculating killer – though a deluded man of some intelligence, who in his 1,500-page manifesto reveals a knowledge of the history, culture and politics of Europe. … Angela Merkel of Germany, Nicolas Sarkozy of France and David Cameron of Britain have all declared multiculturalism a failure. From votes in Switzerland to polls across the continent, Europeans want an end to the wearing of burqas and the building of prayer towers in mosques….awful as this atrocity was, native-born and homegrown terrorism is not the macro-threat to the continent. That threat comes from a burgeoning Muslim presence in a Europe that has never known mass immigration, its failure to assimilate, its growing alienation, and its sometime sympathy for Islamic militants and terrorists.”

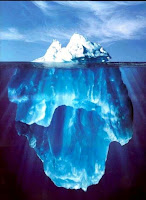

People are justified in wondering about the mental state of Breivik- or anyone that could commit such atrocities. However, writing Breivik’ off Breivik’s actions as isolated, irrational and crazy closes out space for talking about the potential iceberg of racists anti-immigration attitudes that his actions sit atop of.

Megan MacKenzie is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney in Australia. Her main research interests include feminist international relations, gender and the military, the combat exclusion for women, the aftermaths of war and post-conflict resolution, and transitional justice. Her book Beyond the Band of Brothers: the US Military and the Myth that Women Can't Fight comes out with Cambridge University Press in July 2015.

https://www.cambridge.org/ee/academic/subjects/politics-international-relations/international-relations-and-international-organisations/beyond-band-brothers-us-military-and-myth-women-cant-fight?format=PB

Anyone who thinks that ‘native-born and homegrown terrorism’ of Breivik’s sort is not [or will not be] a macro-threat to Europe does not know his history. Does the name Quisling ring a bell. Pat?

Megan, thank you for an excellent post. I certainly agree with you that the resort to preemptive psychoanalysis is an injunction against asking critical questions. In this light, I wonder to what extent the discipline of political science and international relations also needs to undertake further critical evaluation to discover the regenerative sources of these anti-immigrant sentiments. After all, where do individuals get the notion that some people “belong” in certain places and others do not? How do conceptions of territoriality trap our thinking? How can we deconstruct the links between identity, memory, and territory? While I assume that students across the social sciences in Europe and America are introduced to the notion that nationalism is a social construct, we seem unable to offer alternative modes of re-imagining the relationship between people and place that are more inclusive or generous than vague notions of a “tolerant” multiculturalism.

Great points Vikash. I think you’ve started to answer your own excellent question about the contradictory roots of multiculturalism. I’m not in any way an expert on multiculturalism, but I will say that the new language- particularly within Europe and Canada- focused on ‘social cohesion’ is quite fascinating, and telling. I’ve been looking at the roots of the concept of social cohesion- most signs point to Freud and Durkheim. Freud was primarily talking about male bonding outside the family unit and women as a distraction from men’s need to supress their sexuality in order to bond (this stuff comes in handy when looking at how cohesion is used to justify the combat exclusion for women and the former DADT policy in the US military). I’ll leave Durkheim in case I’m alrealdy boring you. The point is that multiculturalism, social cohesion- whatever the phrase of the day is- still requires some kind of unified society that has ‘shared’ values. In most cases this means that the dominant race and sex set the tone of this group. I’m not sure if I’m remotely answering your question but would love to hear more of your thoughts on this.

This is an interesting analysis and I agree with much of it. The “instant psychoanalysis” of Breivik perpetrated in the media has indeed been based not on any analysis but on the facile equation of heinous act with madness. Certainly this has everything to do with the restriction of political speech to narrow confines as well: so just as Pat Robertson identifies terrorism with a “foreign” other that “refuses” to assimilate and integrate into an imagined Western Christian community — not us and therefore incapable of political speech — defining Breivik as mad also defines his speech as not-political, thus relieving us of the need to examine the politics.

But I don’t want to let go of the notion of pathology. It’s not just that Breivk could be both a sophisticated right-wing thinker and a sociopath, it’s also that his right-wing ideas are pathological or rather, symptoms of a social pathology rampant in the developed capitalist world. Consider how popular the detestable Ayn Rand has proven to be, and all she did was elaborate her own inability to feel with (com-passion), that is, her own sociopathy, into dystopian novels that suggested that the best possible world would be one where you could act without regard for anyone else. That strikes me as a signal failure to integrate the personality so that the self can thrive on mutually gratifying relationships.

It seems to me that we can use psychoanalytic tools to read Breivik’s acts and writings not in order to individualise the pathology (however much he may or may not be a sociopath) but to uncover its roots in the wider culture and the politics that produced him.

These

are thought-provoking points, Matt, thanks for posting them. The question of whether the notion of

pathology could be harnessed to identify and resist right-wing extremism is an

interesting one, and for me echoes long-standing debates amongst critical race,

feminist, and other equity studies scholars on the potential advantages or

disadvantages of “using the master’s tools” (in this case, using psychiatric or

medical diagnoses, or the notion of pathology more generally, as analogies for

describing right-wing extremism). I have four cautionary notes:

1.

Practically, I think this is just not usually how it works: notions of

pathology or madness are most often used to paint someone like Breivik as an

exception, as anti-social (rather than highly social in right-wing racist

circles than span across Europe and beyond).

Much work would have to be done to re-direct this narrative, and I’m not

sure it would be possible to do so, without a narrative of social pathology

collapsing into individual pathology. So, I’m not sure this is practical: it

shares the same pitfalls of strategic essentialism.

2. I

think it is potentially dangerous to use medical analogies of pathology. Traditionally, these analogies have been used

in military strategy: Mika Luoma-Aho wrote an excellent piece (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/714000968) illustrating the notion

that the Balkans represented a pathology in the European body politic, leading

to military intervention. Currently, US

military doctrine on counterinsurgency similarly casts ‘insurgency’ as a

pathology, and likens military intervention to a surgical intervention. Following the logic of a medical analogy:

what do you do with a pathology? You excise it. In the contemporary moment, ‘excision’

almost always means military force of one kind or another. The language of pathology in IR is deeply

tied with militarism, and so I think we should always keep this in mind when

thinking in terms of pathology.

3.

Related to this last point, I think we need to deal with the politics, and not

the psychology of right-wing extremism, either in individuals or in broader

social terms. Saying that these

people and groups simply lack compassion forecloses thinking and engagement,

rather than opening up politics.

Right-wing groups, like those Breivik associated with, are political. Setting them up as ‘socially pathological’

can lead to a failure to fully understand the contexts of these politics, and may

also set up those of us who oppose right-wing extremism as uniformly ‘healthy.’

Transposing the pathology from the individual to the social doesn’t really

solve the problem: as much as we may vehemently disagree with such politics,

treating right-wing politics as such is

the best way to counter them.

4. I

refer again to point number two of our original post: that it is wrong to

equate violence and madness, or even right-wing extremism and pathology,

because it does a tremendous disservice to all of those activists who are

currently struggling – up a steep hill! – to change common perceptions of what

it means to be mad. Madness is being

reclaimed as a positive term, and as a basis for action against psychiatric

systems (systems which have historically been tied very much to capitalism, fascism,

colonization, racism and sexism). Let’s not make that hill steeper by investing

in such ill-defined and highly disputed notions such as sociopathy, or by continuing

to think, act, and speak in terms that equate madness with pathology, danger or

violence.

Thanks

again for your post Matt: thought-provoking stuff.

Hi Alison:

I really appreciated your and Megan’s post. As a Mad-identified scholar engaged in critical equity studies, I grow weary of engaging in converations that work to explain racism, violence, and discriminations within social psychology models. Social Madness (and all similar terminology) inherently implies that madness is a negative state that results in both individual or social detriment. Characterizing individual or social violence as “madness” further contributes to the sole focus on negative aspects of madness, and solidifies madness as an undesireable attribute — something that Mad Studies and Mad Pride is trying to end. Working within psy discipline frameworks to explain away societal or individual behaviour as pathology simply furthers entrenchment of such disciplines, which have their very own violent and discriminatory histories against those that they profess/ed to serve. Allies can do better, and this conversation helps.

Hi Alison, thanks for taking all the trouble to respond to my back-of-the-cocktail-napkin assertions! A quick response here, mostly for the purpose of self-clarification.

Point by point: 1. Yes, I agree that this is how notions like “mad” or “psychopath” are used and I’m not sure I am in any position to re-direct any narratives. I think I wanted to make a slightly different point, that a more robust psychoanalytic approach does not have

to be made at the expense of good political analysis. Here I feel much closer to Žižek or Lacan than, say,

to Deleuze and Guatarri.

2. Yes, I strongly agree. I do not want to use “pathology” as an analogy or metaphor. Those arguments that treat people or even political acts as “pathological” ought not just be written off as bad analogies, however; they need to be subjected to the kind of rigorous critique you’ve engaged in here (I don’t know the piece you cited but I will look it up). If “pathology” is an analytical concept and not (only) a metaphor, using it analytically has consequences that ought to be spelled out.

3. Yes but here again, I would just pipe up to repeat that this doesn’t have to be an either-or analysis. Or more: yes, it is urgent to deal with the extreme right’s politics (almost as urgent as it is to deal with liberalism’s politics) but to do so, psychoanalytic tools may be helpful, and not the hindrances that the “instant analyses” you and Megan so cleanly deconstruct here are.

4. Yes, again I do agree and I hope I wasn’t suggesting that Breivik is violent because he is mad (or, as the media reduction asserted, mad because he is violent). I don’t want to “equate” anything with anything else (a tall order!). This is how I would defend (breifly and very simplistically, sorry!) my notion that thinking in terms of sociopathy is helpful: (part of) what is troubling, as we seem to agree, about the definition of Breivik as a madman is that to define him so is an attempt to place him beyond politics. If he’s “mad” then he’s not a human animal capable of political speech (just as “mediaeval” Islamic terrorists are defined as so other as not to belong to the political community) and we’re all spared doing the political analysis. So the pathology shows up in two dimensions: first, Breivik’s own embrace of political ideas and tactics that are orientated towards an instrumental use of others (lack of compassion) to create a community hostile to difference (relieving that community of the need for compassion). Second, in the anti-political exclusion of Breivik’s speech (acts and text) by those analysts who pigeon-hole him as “mad.”

By the way, I hope you approve of my use of the scare quotes around “mad” though I apologise if my inelegant use of the word just muddies what I’m trying to say. I agree with what you had to say about the political struggles of mad activists. The political point here would just be that to be able to hear the cries of people in pain without patronising them requires us to hear them as political animals.

I know the point has been made before, but Islamists are rarely referred to as pathological. Perhaps the solution here is more opening up to disaffected segments of society rather than a clamping down.

Breivik is not a racist– he is a white (nonhispanic cauc) conservative christian nativist. He shares ideology with the American Tea Party and the British EDL.

His views were largely formed by the online counter-jihaadi community– Gates of Vienna, Pam Geller, Robert Spencer, fjordman, etc.