When I was in graduate school I tried my hand at writing speculative fiction (SF) and fantasy. I even hung out on usenet groups and joined an online writing circle. I flatter myself that, with enough work, I might have improved the quality of my scribblings from “crappy” to “passable.”

It turns out that I chose the wrong career. It isn’t just in the social sciences that atrocious writing, wooden characters, and unimaginative plot lines present no barrier to awards and honors!

As David Moles writes:

Last month [i.e., two months ago] the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America gave a Nebula award to a piece that contained no science worth speaking of. There was very little fiction in it either, if fiction is the narrative of imagination; whatever images might have been in its author’s mind, what made it onto the page was determinedly unimaginative, and less narrated than vaguely gestured at. It put forward no fantasy, unless the fantasy that the world is an uncomplicated place populated chiefly by straw men and contrived examples is a fantasy. What writing was in it was mostly bad.

Moles isn’t kidding. Eric James Stones’ “The Leviathan Whom Thou Hast Made” is just plain awful. But it has inspired some truly entertaining critical discussion. Check out Martin Lewis’ review. Also of interest: Abigail Nussbaum’s commentary on the Hugo short-story nominees.

What’s wrong with “Leviathan” isn’t just that it’s badly written and that all its characters seem to have been created either to spout talking points (the titular Leviathan just happens to say something that echoes the book of Job) or act as straw men (the anthropologist who, against her better judgment, ends up helping the narrator, and along the way lobs softballs at him and acts like a stereotype of a disdainful atheist; interestingly, the one good point she makes–pointing out that the only reason the Mormon swales care that they’re being raped is that their new religion has taught them to view sex as a sin–is completely ignored by both the narrator and the story). Worse than these is the fact that it’s not a story so much as a thought experiment that posits a situation in which none of the negative associations of Christian missionary work are applicable….

Nussbaum is certainly correct on this last point, but I think it would be a shame to the let political objections get in the way of the story’s utter lack of aesthetic merit.

Nevertheless, Nussbaum makes some other interesting ponts about replacing advanced aliens for humans.

It is a little like the way that creators of war movies have been gravitating towards the alien invasion premise (Skyline, Battle: Los Angeles, the upcoming Falling Skies) as a way of getting around the fact that it’s no longer acceptable to use the Russians or the Chinese as faceless hordes of evil invaders, or the way that the creators of Avatar tell the utterly familiar story of a white man who not only saves the Native Americans but is better at being Native American than actual Native Americans, but insist that they’re not being racist because the story is set on another planet and among aliens.

This all bears a family resemblance, I might add, to the status of Orcs as fit targets of genocidal eradication in The Lord of the Rings, an issue that Peter Jackson cleverly obfuscated by turning the Orcs into broadsword-wielding proto-industrial national socialists, intent on committing genocide against humankind.

Nussbaum’s post is worth reading in full. In part, it makes clear the thickly intertextual quality of speculative fiction and fantasy–and of its “involved” community. This aspect of the genres carries with it significant costs. It creates high barriers to entry. For example, I am more than a casual consumer, but I find the complexity of knowledge required for serious analysis simply overwhelming. It also place far too high a premium on originality.

Genre fiction is defined, more than anything else, by audience expectations. The best work, it seems to me, meets those expectations while also entertaining, prodding the intellect, and evoking emotion. One way to accomplish those goals, of course, involves playing with audience expectations. But there’s a lot to be said for the artistic merits of a well-crafted pop tune. Perhaps more attention to those sorts of merits would discourage the production, as well as the granting of awards to, pretentious and didactic garbage.

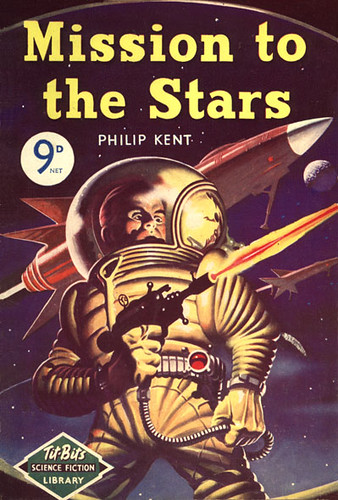

(For more bad SF cover art, see Flavorwire)

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

0 Comments