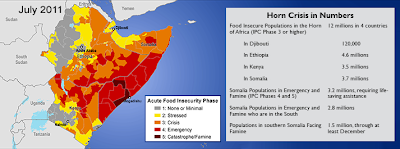

So, I will ultimately come back to climate change and public opinion in this country, but when I haven’t been handwringing over the debt ceiling, I’ve been preoccupied by the humanitarian tragedy unfolding in Somalia and East Africa more broadly. I’m going to tackle this topic in a couple of parts since this post is already quite long. The United Nations estimates that as many as 11 million people are being affected by the current crisis, seen as the worst drought in the region in 60 years (see the FEWS NET map of the extent of the crisis below).

Why is this crisis emerging now, and why are the numbers of people affected as large as they are? Drought and famine of course are nothing new to East Africa and the Horn. We all remember Bob Geldof’s Live Aid concert from 1985 which was organized as a response to Ethiopia’s famine. Of course, the United States sent in more than 20,000 soldiers to Somalia in 1992 in response to the then famine, a mission that went disastrously awry when the Clinton Administration broadened the effort to go after warlord Mohamed Aideed.

Aside from the obvious and important humanitarian issues at stake, the current crisis raises a number of interesting issues about vulnerability to extreme weather events. How much is this famine a function of physical exposure? In other words, is this a really bad drought? Relatedly, does this current drought have anything to do with climate change?

A number of observers think so. Jeff Sachs makes the case that:

The west has contributed to the region’s crisis through global climate change that victimises the lives and livelihoods of the people of the region.

USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah made a similar statement:

There’s no question that hotter and drier growing conditions in sub-Saharan Africa have reduced the resiliency of these communities. Absolutely the change in climate has contributed to this problem, without question.

More credible arguments come from David Orr of the UN World Food Programme:

It is extremely alarming that the incidents of drought seem to be occurring more and more regularly. There was a gap. The general view was that extreme weather events were occurring every 11 years. Then it came down to five or six years. But the last drought in this region occurred in 2007 and 2009. So they do seem to be happening with increasing regularity, undoubtedly as a result of climate change.

Such views were reiterated by Valerie Amos, UN Under-secretary of Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator:

We have to take the impact of climate change more seriously. Everything I’ve heard has said that we used to have drought every ten years, then it became every five years and now it’s every two years.

There is a tendency in the environmental and wider policy community to link almost any extreme weather-related event with climate change, even though other processes like El Niño or La Niña may be more to blame. At the same time, even if climate change is a possible culprit for increasing severity and number of droughts in the region, the science of attribution of particular climate-related events is in its infancy and highly contentious.

Neither Sachs nor Orr are natural scientists so what is the scientific community saying about the role played by climate change in the region? Some scientists have begun to argue/speculate that climate change may have a role to play in the current drought and going forward.

Chris Funk from the U.S. Geologic Survey (who also advises FEWSNET) has put forward a provocative argument, suggesting that climate change has intensified the effects of La Niña. He has a recent paper in Climate Dynamics that suggests drier conditions in East Africa will continue because of climate change. He attributed the lack of rain to warming over the east Indian Ocean and the extension of the Tropical Warm Pool, which originates in Indonesia:

It really seems as if the warming of the central and southern Indian Ocean is contributing to more frequent droughts and intensification of the impacts of things like la Niña.

It’s warmed about a degree over the last 30 or 40 years and maybe about half a degree over the last 20. But the reason that it’s important is that it’s already really, really warm. And so, as far as we can tell, that warming has triggered more rainfall over the central Indian Ocean. And that rainfall basically pulls in moisture from the surrounding area and prevents it from going onshore into Africa.

The sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean are really well correlated with global temperatures. So, the past 150 years, as far as we can tell, the Indian Ocean has gone up and down very closely with global temperatures. I’m not sure that we fully understand why that is, but it seems to be an area that as we’re experiencing global warming the Indian Ocean is warming up right in step with that.

His views are a bit more nuanced as he noted that other areas in East Africa may get greener.

In central and eastern Kenya, it looks like the rainfall is decreasing. But as you go towards Lake Victoria, the rain there has remained steady. And so there’s a lot of opportunity for developing agricultural resources in the west that won’t be affected by climate change. And a similar situation exists in Ethiopia, comparing the north versus the south.

Funk is a geographer by training (does this matter that he’s not a climate scientist? Not sure). What’s more, most of the projections for East Africa suggest that the region is likely to get wetter with climate change not drier. I asked a colleague of mine from UT who does climate projections about this and here is what they said:

You are right that the IPCC AR3 models projected wetter conditions over the GHA – farther south than Somalia in general – with confidence derived from a certain level of agreement among the models. Also, when the Indian Ocean is anomalously warm, for example as often happens during an El Nino event, East Africa is often wet. But attributing a cause for the current drought in East Africa would take some considerable study – including model simulations – that no one has yet done.

Some of that modeling work may have been done by Funk and some of his collaborators. I tracked down another paper in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences from Chris Funk along with colleagues from NASA and the USGS. That project looked at 11 climate models and tried to simulate rainfall changes in the future. 10 of the 11 models suggested that through 2050, rainfall over the Indian Ocean would increase, suggesting less rainfall on land. Funk argued that:

We can be quite certain that the decline in rainfall [over East Africa] has been substantial and will continue to be. This 15 percent decrease every 20-25 years is likely to continue.

However, based on its review of multiple studies, the 2007 IPCC Fourth Assessment concluded:

There is likely to be an increase in annual mean rainfall in East Africa.

The 2007 IPCC report summary of model projections of projected rainfall shows nearly 20 models projecting higher rainfall over East Africa in most months. Look at the bottom left two frames for annual rainfall totals and December to February projections.

Figure 11.2. Temperature and precipitation changes over Africa from the MMD-A1B simulations. Top row: Annual mean, DJF and JJA temperature change between 1980 to 1999 and 2080 to 2099, averaged over 21 models. Middle row: same as top, but for fractional change in precipitation. Bottom row: number of models out of 21 that project increases in precipitation.

So, what do we make of this disparate evidence? I can’t say I fully grasp the reason why these models are showing such discrepant findings, and I’ll post an update should I get some clarity. In the meantime, I think the jury is out on the science, that it is too soon and too uncertain to make a strong case that there is a clear climate signal behind the on-going drought in East Africa. I’d like to see if the fifth IPCC assessment report revisits or revises the anticipated rainfall dynamics for East Africa. The Working Group I report should be out in September 2013, but we will likely have some reports of drafts well before then.

In my next post, I’ll talk more about how we get from drought to famine, and the relative causal weight of physical factors compared to political and economic factors in the current crisis.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

The IPCC are a buch of liars.

here is but one example.

Why would you take anything that comes out of the UN seriously? They are cut from the same cloth as our Democrats: Anti-Western, elitist Marxists out to destroy the West and grab some of the taxpayers money.

There is not such thing as AGW or man-made “Climate Change”, and it is absoultely ridiculous to imagne that “Europe” or “The West” causes harsh weather or deforestraton in Afrca. There is ablustley no clear science or emperical proof for these claims. There is ust rhetoric masked in “scientific” mumbo-jumbo. IT is happenstance and their own iditic approaches to agriculture that is the problem.

Why do you have to “wait for their next report”? Just read any of the prior ones–nothing will have changed for the simple reason that they are ideologues pushing propaganda and not in any real sense of the word are they “Scientists”. Pray tell, just what would “Climate Science” be, as opposed to say Physics or Chemistry? There in fact is no such thing as “Climate Science” as a scientific discipline. It is a totally bogus construct. Goodness, we cannot even predict the weather out 5 months. If a Physicist stood beofre his colleagues with this sort of shoddy, politicized and opinionated “work” he would be laughed off the stage. That these so-called “Climate Scientists” get away with this sort of stuff proves that there are very few real scientists–or even critical thinkers–in the bunch.

Wow, that didn’t take long (see other comment).

I wonder how they show up so fast.

RSS feed or Google alerts with climate change or IPCC as keyword? We shall find out!