In this third post about the Horn of Africa and the ongoing famine, I thought I’d address what should be done, which seems appropriate given the visit today to the region by a team of U.S. officials, including Jill Biden (wife of the vice president), USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah, among others. My first two posts assessed (part 1) whether or not climate change could be implicated in the current drought (uncertain) and (part 2) the relative causal weight of the drought itself compared to politics in the overall famine (drought itself more important than some seem to believe). In this post, I examine what should be done in the short-run. I’m going to leave long-run issues associated with state capacity and resilience and the future of pastoralism for a fourth post.

The Short-Run: Emergency Relief

Finance

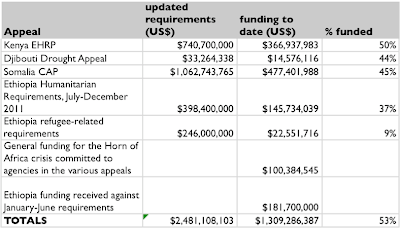

Obviously, in the short-run, the people need help in terms of emergency assistance. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has put out appeals for nearly $2.5 billion dollars for the region, of which about 45% has been funded (though slightly more than 50% if you include funds raised for Ethiopia at the beginning of this year). The United States is by far the largest donor, having committed/contributed nearly $460 million.

|

| Funding Status: 2011 Horn of Africa Drought according to the Financial Tracking Service (FTS) |

The African Union’s fundraising conference to discuss the need was inexplicably postponed from last week until August 25th, but perhaps this shortfall will be partially met in a few weeks time if not sooner.

For people reading this blogpost who want to help, there are a number of different NGOs and international organizations working in the region worthy of your support, most of them the usual suspects in humanitarian relief like Doctors without Borders, the Red Cross/Red Crescent, and the World Food Programme. The ONE campaign has compiled a list of different organizations. For those interested in Ethiopia in particular, an Austin-based charity Glimmer of Hope has extensive experience working there and has launched an emergency appeal.

Access

However, money alone is not the answer. There are strategic choices associated with how to ensure emergency relief gets to the people in the short-run. Many of these short-run decisions will have a bearing on a number of long-run concerns, including how (and whether) displaced populations can return home and resume their livelihoods and whether any semblance of a functional state can be restored to Somalia.

Some short-run issues have been partially dealt with. In mid July, after a protracted delay, the Kenyan government finally agreed to open Ifo II, a refugee camp that can hold 80,000, which should ease some of the pressure on the other three camps in the Kenyan town of Dadaab (though the camp had yet to open as of July 28). It is less than ideal to have refugees streaming into Kenya or Ethiopia with limited prospects of ever returning home. The journey itself is extremely dangerous for the migrants, and life for them in the camps, particularly if prolonged with no possibility of broader mobility in the host country, cannot be all that pleasant. However, such are the hazards of staying in Somalia that people have been willing to risk the trip.

Given the limits imposed by the al Shabaab militia on aid groups operating in Somalia, Robert Paarlberg argued that:

The best policy option that the international community has available to it in Somalia is to support as much as possible the feeding operations now underway in the sizeable territories not controlled by Al-Shabab.

Recent events suggest there may be more scope for aid delivery in Somalia, even in al Shabaab controlled areas. On August 2nd, the U.S. government lifted the enforcement of sanctions for groups funded by the U.S. government against working with al Shabaab (because of the group’s presence on the State Department’s terrorist group watch list). That said, U.S.-based aid groups that receive funding from non-U.S. government sources worry that the new guidelines will not shield them from the anti-terror laws.

While there are encouraging reports that the first airlift of food aid arrived in Somalia, stories on the ground about the distribution of aid raise worrisome questions. Late last week, seven people were killed when a Mogadishu relief camp was set upon by people intent on looting, possibly including government soldiers.

Al Shabaab’s resistance to assistance may be starting to change as the militia loses popularity with locals given the draconian restrictions the group imposed on aid workers (including violent attacks). The group itself has fragmented into factions, some more willing to allow aid workers in to the country. On Saturday August 6th, Shabaab fighters vacated Mogadishu, leaving the city in the complete control of the weak Transitional Federal Government (TFG) for the first time in years, raising hopes that the 100,000 new internally displaced persons (IDPs) who have descended upon Somalia’s capital can finally receive assistance relatively unimpeded. Al Shabaab’s long-run intentions remain unclear, as their retreat appears to have been tactical.

With the Shabaab departure from Mogadishu, the TFG in particular — assisted by the 9,000 African Union troops in Mogadishu — has a limited opportunity to burnish its badly tarnished reputation and secure control of the capital (though few should have any illusions about its capacity or the public-mindedness of its leaders).

Sourcing Food Aid

While finance and access issues are important, decisions made now may affect long-run incentives in the region, particularly with respect to agricultural production. CFR’s Stewart Patrick suggests America’s policies of relief may be part of the problem. Referencing 2009 work by his colleague Laurie Garrett, Patrick notes that U.S. policies of food aid have undermined local agricultural capacity by airlifting U.S.-grown agricultural supplies rather than relying on regional food sources, as other donors have increasingly done.

U.S. food aid procurement practices are slowly starting to change, beginning with the 2008 Farm Bill which authorized $60 million for a pilot project on Local and Regional Procurement (LRP). Prompted by a 2009 GAO report that suggested local purchase of food could be significantly cheaper and faster to deliver to needy areas, the U.S. has been experimenting with cash-based food assistance schemes, local and regional procurement, and food vouchers through the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP).

|

| GAO 2009 |

Through June 29, 2011, FY 2010 and FY 2011 expenditures reached $339 million, with Pakistan being the main beneficiary ($182 million) followed by Haiti ($47 million), Niger ($26.8 million), and Kenya ($20 million). Given that the U.S. provided $2.9 billion in food assistance in FY 2009, this amount of regional procurement is obviously a drop in the bucket.

Through June 29, 2011, FY 2010 and FY 2011 expenditures reached $339 million, with Pakistan being the main beneficiary ($182 million) followed by Haiti ($47 million), Niger ($26.8 million), and Kenya ($20 million). Given that the U.S. provided $2.9 billion in food assistance in FY 2009, this amount of regional procurement is obviously a drop in the bucket.

Given that totals of regional procurement through the EFSP mechanism are relatively recent, this also implies that most of the food aid in the current crisis is being brought in from afar through traditional mechanisms of in-kind donations.

Even if it were desirable to buy more food regionally, it’s unclear given the wider problem of spiking food prices whether there is regional capacity to produce and distribute enough food. Tanzania reported a surplus of 1.7 million tonnes of food that it is willing to export (though I’m not sure how that relates to total need). Kenya for its part has reported food surpluses in parts of the country of such produce as cabbage and potatoes, but the country lacks storage and transportation infrastructure to get their products to needed areas without spoiling.

|

| Plumpy: Fortified Peanut Paste |

Issues of inadequate infrastructure obviously cannot be resolved in the next few weeks. However, there may be opportunities, as in Tanzania, where more local sourcing of food could be appropriate. While local food sources are important, the nutritional needs of people in the region are such that the World Food Programme is providing fortified emergency rations, such as Plumpy’Sup peanut paste, sprinkles of micronutrients, and high energy biscuits.

While some countries such as Malawi have factories that produce so-called ready to use therapeautic food (RUTF), the production capacity of the rest of the continent may be limited. In 2010, there were 14 suppliers of RUTF that UNICEF used to supply Africa, seven global suppliers (including a South African firm) and seven local suppliers (one in Niger, one in Ethiopia, two in Malawi, one in DR Congo, one in Madagascar, and another in Mozambique). Given limited production capacity, the specialized food needs of populations may require airlift of these supplies into Somalia and surrounding countries with food grown outside the region. However, over the longer run, this is a less satisfactory situation, given that food aid may depress local incentives for food production.

Thinking about the Long-run

As many observers have noted, media and resources disproportionately flow to this region when there are emergencies, which surely does immediate good in preventing starvation (and enhances the prestige of relief groups). However, whether these emergency interventions facilitate a transition from crisis to development and state capacity is less clear. As resources flow to the region, current programs have to quickly envision the measures that would make the next crisis less likely. Oxfam’s Semhar Araia made the case for such a response in a recent Brookings forum:

So what’s needed in the future is international community having an agenda that also includes a long-term response. The lack of long-term economic development in this region has meant that we’ve seen a series of short-term humanitarian interventions and emergency responses and a failure to really establish and strengthen the infrastructure for economic development.

Pierre Salignon of Doctors without Borders made the point more trenchantly and said there is no humanitarian resolution to the crisis in Somalia. A policy of abandonment of Somalia inevitably means that another crisis will reoccur:

In the absence of a long-term vision, the international community, in the form of the United Nations, is satisfied today, as it was yesterday, with temporary, humanitarian solutions to each fresh crisis, in the time it takes for attention to move away from the Horn of Africa and its starving populations deserted by their own governments. And why should tomorrow be any different?

Just to tip my hand a bit, absent some internal breakthroughs on state-building in Somalia, I’m not certain that technocratic development projects are likely to offer the region that much potential. I’m also not convinced that communities at most risk, particularly pastoralists, have livelihoods that can adapt all that well to the modern age. For my fourth post, I’m going to tackle long-run issues of state capacity and resilience and the future of pastoralism.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments