Here is part one, where I argued that international relations as a field has become increasingly uncomfortable with the America’s post-Cold War hegemony and the level of force used in the GWoT, but…

2. We’re drifting toward R2P

Simultaneously, we are elated that the Libya operation worked, (against all odds given the Iraq experience and what we know about foreign intervention in LDCs generally). Lots of Duck writers supported the intervention. (I found Jon Western’s arguments last spring particularly persuasive; some of my writing on Libya is here and here.) Even if you didn’t support it, and worried that it meant more ‘empire,’ it still tugged at your heartstrings to see Libyans fighting and dying against a nasty tyrant. So you probably supported the NATO intervention even though you didn’t want to.

We realize that dictatorships are extremely vulnerable only in short windows which the regime will close as quickly as possible with as much blood as necessary. If there is anytime that Syria or NK might switch to more humane governance, it looks like now, when the center is weak. As with Libya, there is a window of opportunity that is deeply tempting, despite our broad sense that the US is doing too much and killing too many people. But given how rare revolutions like Libya are, it feels ridiculous, almost immoral, to miss such a unique, human rights-improving opportunity on behalf of a generalized principle like retrenchment (‘make me a non-interventionist, but not yet’).

Further, there is growing body of evidence that intervention can actually work pretty well and most crucially reduce the killing. How many more times can you teach the Holocaust or Darfur or the Khmer Rouge or ‘rape as a weapon’ in class before you personally agree with R2P? For me this has been fairly central. I worry a lot about US ‘empire,’ but I find teaching the material that we do in IR to be so disturbing sometimes, that it makes me an unwanted interventionist. I often wonder how undergraduates must think of us as we calmly explain the ‘nuclear calculator,’ or how to gauge who is history’s worst genocidaire. So even if we broadly want US retrenchment, we are keen enough to realize that R2P is genuinely appealing and that the opportunities for it to be effective are both rare and short. Ie, if we don’t move quickly to help places like Libya and Syria when the rare opportunity arises, we leave them to yet further decades of repression. Who wants to explain that away? And realistically the only state with the ability to push through meaningful R2P interventions is the US.

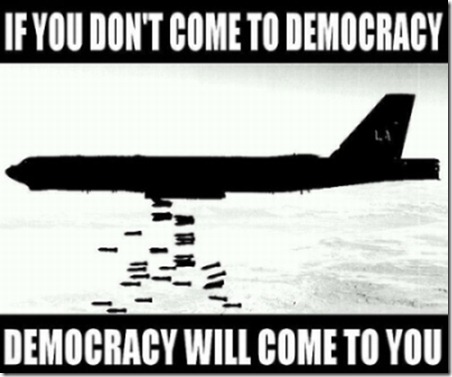

In brief, the bulk of IR scholars today normatively wants two things increasingly at odds, I think: 1. a slowdown, if not end, of the GWoT – torture, indefinite detention, Guantanamo, drones, Islamophobia, national security state overkill, domestic militarism, and the relentless killing. 2. R2P – taking advantage of the momentary weakness of truly awful regimes to push through desperately needed liberal changes in the name of humanitarianism. The former results in the (much-wanted) demilitarization of US foreign policy and domestic culture, while the second requires a large, interventionist US military, because honestly, no one else can do really R2P besides the US.

I guess if you are Walt or Layne or Ron Paul, these aren’t in conflict. Realist ‘retrenchers’ think the second goal is fairly illusory, so they are comfortable foregoing it to get the sorely needed de-militarization of US life. But the work of Pinker, Goldstein, Western, the democratic peace, even the end of history, makes me more confident that humanitarian action can work and that at least minimally liberalized states can get along without killing each other or their own people. It is awfully tempting to think that just a little bit more exertion, a little more defense spending, a little more covert assistance could help push through desperately needed change in places like Syria or Zimbabwe…

But that’s exactly the ‘utopian’ attitude toward force that realists from Morgenthau to Walt would disparage, right? One small step leads to another to another, and pretty soon you’ve got US empire to handmaiden democracy everywhere all the time, with all the militarization, killing and other unintended consequences such a project must inevitably entail.

Does anyone else see these goals as an irresolvable dilemma? And what is the answer?

Cross-posted at Asian Security Blog.

Associate Professor of International Relations in the Department of Political Science and Diplomacy, Pusan National University, Korea

Home Website: https://AsianSecurityBlog.wordpress.com/

Twitter: @Robert_E_Kelly

0 Comments