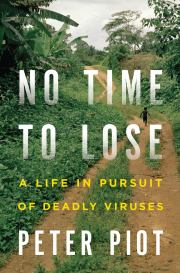

I just finished reading Peter Piot’s lively memoir No Time to Lose of his time as an epidemiologist helping identify the Ebola virus in the 1970s through to his service as the first director of UNAIDS. It is an engaging read not least because Piot conveys a profound empathy for those affected by disease. Piot also projects additional warmth and humanity, from his appreciation for Congolese music to good beer.

More substantively, Piot has a proportionate sense of the outrageousness of bureaucratic politics in the UN system, while recognizing the need to navigate in those shark-filled waters.

Unlike many memoirs, there is some bite here, with some choice words for donors who talk a big game but don’t provide much money (here, France and Italy were named) to mid-level careerists who put turf before those they are meant to serve, as well as some for campaigners whose occasional “extreme” demands or tactics can backfire (his account of an AIDS activist calling France a shit-hole on a live fundraising telethon was on point here).

One aspect of the book made me rethink what I thought I knew about transnational advocacy movements, and his epilogue made me question what scope there is for coordination not only in the UN system but also within the interagency process in the U.S. government.

But by the turn of the of the millennium our “brilliant coalition” was taking shape in its diversity and apparent chaos. What could the South African Chamber of Mines, Anglican Church, Community Party, and trades unions have in common with the Treatment Action Campaign, Medecins Sans Frontieres, and UNAIDS? A common goal: defeating the AIDS epidemic and caring for its victims. A powerful joint desire to be a force for change.

Over the years I became increasingly skeptical as to whether the current UN coordination governance could ever by effective operationally, despite the goodwill of many, if not most, staff. The two main obstacles for delivering as one UN were the institutional interests of individual agencies — careers, political influence, budgets–and the incoherence and volatility of its member states, which not only had different, sometimes mutually exclusive, interests, but which also lacked internal coherence…

Here, Piot’s conclusions are ones we should take to heart when we think about global and national governance of development, health, and foreign policy writ large:

My conclusion on UN coordination was that it was a collective failure, and that the international community goes for some bold mergers and acquisitions as the current plethora of organizations is too expensive, or that it accepts that pluralism is a strength, as long as only effective and well-managed institutions are supported and others closed down.

Interestingly, he suggests that setting up institutions outside of the UN system like the Global Fund is “not a solution” as much as he tried to make it a success. Frankly, I’m not sure what to do with that.

Any Regrets?

Piot at one point, in what might be a veiled reference to the duo, dimisses efforts to identify what prevention strategy worked in Uganda to stem the tide of new infections – was it A (abstinence), was it B (be faithful), or was it C (condoms), writing: “However, some scientists and journalists continue to fuel the debate in a fairly obsessive search for the magic bullet in HIV in prevention…” And to be fair, Halperin has long been obsessive about male circumcision, but as I wrote in a piece for CSIS in 2008, perhaps rightfully so.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

Great review, Josh! Your and Piot’s point that govt officials are advocates is exactly right; often they are the most powerful, especially if they are in domestic institutions. NGOs and others spend lots of time cultivating them and trying to coopt key institutional positions, both national and international. The only thing I’d add, again tooting my own Global Right Wing ‘s horn, is that in many cases there is jockeying for these positions between rival networks, which are fundamentally divided by ideologies, policy goals, “scientific” data, etc, etc. This often makes for nasty tactics, like those in the circumcision debate Piot documents, and for strange bed-fellows, like the Baptist-burqa network of Christians and Muslims opposing gay rights, which I analyze. Scholars have spent far too much time on cooperative strategies, abstract logics, and left-wing networks, neglecting comparable right-wing ones and the divisive strategies all sides use in fighting one another.