There’s much to like about what George R.R. Martin does in his juggernaut of a fantasy franchise: his juggling of a ginormous cast of compelling characters, his willingness to kill and maim those characters in horrible ways, and his relentless critique of the way that high fantasy handles class and gender.

I appreciate that there’s something barking mad about demanding ‘realism’ in fricking high fantasy, but medieval Europe was not populated by well-fed and endearing freeholders, chivalrous knights, and free-thinking warrior-maidens. And let’s not even get started on whether the political economy of feudal society is compatible with low-cost extra-dimensional energy sources.

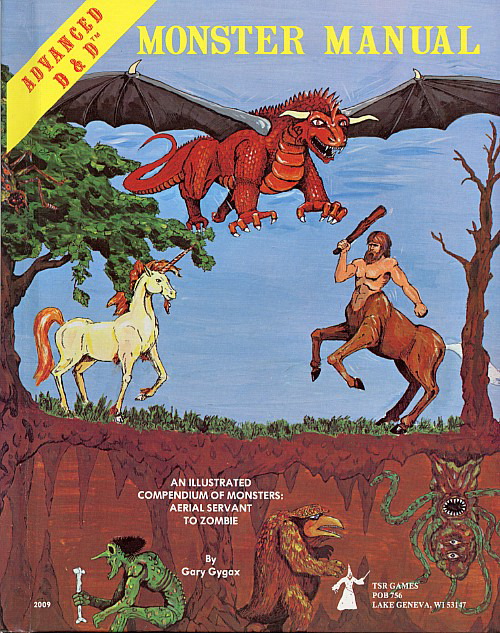

Given all of the ways in which Martin breaks with tropes found in the bulk of high fantasy, it can be easy to forget the degree to which his underlaying fantasy architecture is dungeons-and-dragons level pastiche — complete with Dire Wolves, cliché “barbarian” steppe nomads, pseudo-vikings, and other flotsam and jetsam from Advanced Dungeons and Dragons.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

0 Comments