|

| I have 50+ similar pictures of me standing with KIS murals, statues, busts… |

I went to NK this summer. In my first post, I noted how NK should probably be re-named Kim-land. Here are some more impressions:

1.a. Kim Jong Un was not so emphasized.

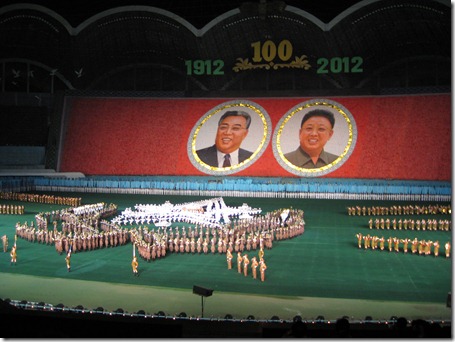

In passing, it is worth noting that KJU was not stressed that much. At the Arirang games, portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il were put up, but not KJU. Nor did we see any images of him at all. No portraits or murals. There were a few slogans using his names, but no imagery anywhere. We were told that is because of his modesty. He does not want to so glorified while he is still alive. I don’t buy that for a moment. Maybe it suggests he is still getting a hold of the state? Not quite sure what to make of it.

1.b. KIS and KJI equally deified?

Also noticeable was the equality between KIS and KJI, which surprised me. At the most famous image of KIS, the Mansudae grand monument, KJI has been placed right next to him, in similar size and on the same plane. The kremlinologist in me noted right away that KIS was not elevated above his son. This was also the case for their images on horseback at Mansudae Art Studio and when their images were presented to us at the Arirang Games (below). I kept trying to get a sense of which one was more important or greater, but couldn’t (and the guides ducked any questions that even hinted about this).

I kept thinking of how Stalin was placed in the Red Square mausoleum next to Lenin immediately after his death, but then, with destalinization, he was removed. He was buried behind the mausoleum, and even under the partial re-stalinization of Brezhnev, he was not put back. NK arguably reached its high point under KIS, who seems a little less dangerous than his son was. I wonder if a ranking will eventually emerge?

2. Get your terminology right!

My Korean is already an embarrassment, but all the unique NK vocabulary made it a pain and signaled that I had training in SK. Korea was ‘Choseon’ not “Han-guk,” which I knew beforehand but kept forgetting to say. This was politely ignored, but no one teaches you how to say ‘long live the great general comrade KJI’ in SK language schools. D’oh! And the Marxist-Juche vocabulary was a even harder – I don’t think I ever learned the word for ‘peasant,’ because there aren’t any in SK, but now I know. I would also forget to attach titles to KIS and KJI, like ‘comrade,’ ‘general,’ etc, which the guides were fastidious in using. I also kept almost using the South Korean parlance for North Korea (buk-han), which was a major mistake, but the words DPRK in Korean were a mouthful to learn. All in all, I kept putting my foot in my mouth.

3. Not as much propagandizing of the tourists as I expected.

I heard that visits to the Soviet Union involved a lot of ideology and agit-prop for the tourists, but this wasn’t the case for us. Maybe with the Cold War over, the travel service realizes we’d just fall asleep if they rolled that out. But I was surprised given NK’s reputation and the very obvious efforts to indoctrinate the N Koreans themselves. Occasionally we got guides who seemed like true believers, and the video at the captured USS Pueblo was a real hoot about decadent US imperialism turned back by the quiet heroism and might of the Korean people and so on. But as a rule, we weren’t bombarded by claims about western failure and socialism’s triumph and all that. When unification did come up, the idea of ‘one country two systems’ was the typical response. No one argued for a war (which was hardly surprising I guess, but still nice to hear). We were however sure to be told that the US began the war – not even Syngman Rhee and the South so much as the mi-guks.

4. God forbid you fail on-the-spot guidance.

We heard so much about KIS and KJI coming to this or that location to provide nuggets of wisdom like, ‘this restaurant should serve healthy food and the workers,’ that it got to be second-nature. Typically, when we reached a place or facility, a local guide would tell us what the institution was, and by the second or third sentence, tell us when KJI and KIS came to visit. In the metro museum, these dates were recorded in detail with a light display indicating when, where, and how often. Typically the guidance was banal – this ‘bridge should heroically serve the people’ – which apparently caused the builders to redouble their efforts and dramatically improved the quality of the bridge. Often the guidance was then inscribed into a gold-leaf plaque that was hung by the entrance so that all could read it immediately on entering. Or the plaques would be free-standing concrete edifices, presumably to indicate the enduring strength of the state. On My Paekdu, the locations where KIS/KJI stood were roped off with guards drifting about.

One moment stood out. We visited a collective farm that had heavy investment by China. Unlike so much else we had seen, it looked clean and functional. There was no cracking concrete, hulks of blown-out tractors, broken windows, etc. By NK standards, it was a marvel. Yet our local guide made sure to tell us in his second sentence that KJI had approved of it. And she said it in such a way that implied that if KJI hadn’t approved, they might have burned down the whole facility and plowed it under. This site was enormous and represented a large portion of NK agriculture in certain sectors. Yet all that hung on the capricious fancy of one man. The way our guide told us of his approval made it sound lucky that this otherwise excellent facility was approved and therefore operational. Good thing KJI wasn’t having a bad day that time or was otherwise upset – I guess that would have been a good enough reason to deprive the whole country of fruit. This was one of those moments that really reinforced the royalism I argued for in the first post.

More in 3 days.

Cross-posted at Asian Security Blog.

Associate Professor of International Relations in the Department of Political Science and Diplomacy, Pusan National University, Korea

Home Website: https://AsianSecurityBlog.wordpress.com/

Twitter: @Robert_E_Kelly

0 Comments