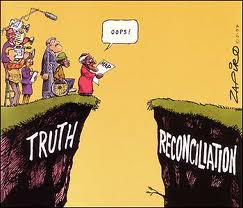

In a recent article by Michal Ben-Josef Hirsch, Mohamed Sesay and myself, we explore broad-based claimed that transitional justice mechanisms are a necessary ingredient in successful peace processes. More specifically, we question the increasingly universal and rarely challenged assumption that truth and reconciliation commissions (TRCs) establish the truth and reconciliation necessary for lasting peace (the TRCs= truth and reconciliation formula).

The truth is that we know very little about what truth and reconciliation commissions actually accomplish. What we do know is that they are the poster-child/perfect case of international norm diffusion. In the span of a few decades TRCs have gone from sporadic events used in random cases of civil war or human rights abuse to a consistent, 100% approved international norm. Most research establishes the prominence of the South African TRC (despite mixed reviews on its success) as a turning point from which TRC became the gold standard in peace agreements- particularly in the global south.

Evidence of the TRC norm abound: First, they are endorsed by most major international organizations working in the area of peace and conflict resolution, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. The UN is such a big fan that it established its own ‘took kit’ for establishing TRCs. Second, transitional justice itself has become profesionalized and institutionalized, particularly through the establishment of the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). In a Foreign Affairs article Jonathan Tepperman summarized the phenomena, stating that ‘the truth business, in short, is booming’ and ‘a new academic discipline has spring up to study the commissions’ pointing to the exponential growth in attention to transitional justice.

Despite all the evidence that TRCs are ‘here to stay’, we still know little about what they do, and if they achieve their lofty objectives. One of the greatest challenges is that the few existing evaluations of TRCs tend to have two major problems:

- Professional bias: evaluations of TRCs often have major conflicts of interest in that it is often advocates or even those implementing TRCs that do the evaluating. Two of the leading and most prolific organizations that study TRCs ar ethe ICTJ and the Role of Law Program at the Untied States Institute for Peace- both major advocates of the processes. Imagine you get to evaluate your own tenure file…you get the point.

- Epistemological and methodological bias: most mechanisms used to assess TRCs, including surveys, focus groups, and quantitative analysis are obstacles to really understanding the local impacts of TRC processes. These methods assume that respondents share a common understanding of major concepts such as ‘peace,’ ‘reconciliation,’ and ‘security.’ This is a major leap of faith considering the disparate locations and contexts TRCs operate in. Generalized surveys leave little space for local respondents to define, explain, or question these key concepts and they do not engage respondents in a manner that solicits local meanings and understandings of the processes of reconciliation, raising questions about how to interpret the results of such studies.

The practical results of such problems mean that claims of TRC “successes” may be based on biased or limited data. Respondents have been found to complete multiple-choice questionnaires in order to satisfy researchers or to avoid being embarrassed (who wants to fill out the ‘no idea’ column? AND if you know the person giving the evaluation also was part of the implementation process, don’t you think it may skew how you respond?). It is not uncommon to have a majority of respondents admitting that they have little or no knowledge about them but that they also endorse them. In a 2003 poll on the attitude of Sierra Leoneans toward the TRC and the Special Court, conducted by the Campaign for Good Governance, it was found that only 17% of respondents understood the purpose of the TRC yet in the same poll it was affirmed that 60% of respondents declared the Commission as beneficial to Sierra Leoneans.

So why all the claims of TRC success and is it possible to better understand the impacts of TRCs?

Unless the biases in existing research methods are addressed and attention is drawn to the self-fulfilling prophecies of the transitional justice industry millions of dollars will continue to be thrown at these processes at the end of civil wars- a time when neither money nor human capital is in vast supply. There is a need for space in the tightly knit transitional justice landscape for critique and external evaluation- and acknowledgement that such activities will enhance, not detract from the objectives of truth and reconciliation.

Megan MacKenzie is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney in Australia. Her main research interests include feminist international relations, gender and the military, the combat exclusion for women, the aftermaths of war and post-conflict resolution, and transitional justice. Her book Beyond the Band of Brothers: the US Military and the Myth that Women Can't Fight comes out with Cambridge University Press in July 2015.

https://www.cambridge.org/ee/academic/subjects/politics-international-relations/international-relations-and-international-organisations/beyond-band-brothers-us-military-and-myth-women-cant-fight?format=PB

0 Comments