A few weeks ago we saw a nasty eruption of the should “progressives vote for Obama” debate–prompted, ironically enough, by a libertarian columnist. My reaction at the time was rather short. But I feel moved by Russel Arben Fox’s explanation of why he’s voting Green, albeit in Kansas, and the ensuing discussion at LGM, to say a bit more. Note that I’ll focus on the left-wing variant, but my comments apply equally to the right side of the spectrum.

What nags at me about the standard defense of “voting your conscience” is this: it often depends upon assuming that other people with similar ideological preferences aren’t going to do the same (I’m talking specifically about people who share Russel’s position that they would rather see Obama elected than Romney, not the “heighten the contradictions” crowd). Consider the following simplification.

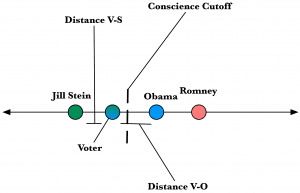

Voter declares, in essence, “I can’t bring myself to vote for Obama. Obama’s policies are a bridge too far.” In essence, Voter’s argument is that:

- Distance(V-S) < Distance (V-O); and

- Distance(V-O) > Conscience.

It isn’t simply that Voter prefers Jill Stein’s policies; Voter has a threshold beyond which he cannot stomach voting strategically. We’ll call that a “conscience cutoff.”

The problem, as I see it, stems from what would happen if we universalized Voter’s behavior (the “voting imperative”). Voter’s argument implies that everyone else beyond the “conscience cutoff” should also vote for Jill Stein. But if they did so, Obama would face a large enough defection from the left to jeopardize a reasonably close election. So Voter is relying on others to behave, on his own terms, “immorally” in order to allow him to (1) take a moral stand and (2) render his behavior irrelevant to the electoral outcome. Or, put another way, you’re counting on others taking the “conscience hit” to afford you the luxury of “moral” behavior.

I’m not sure if this argument applies to, for example, a progressive voter in Kansas. I suspect that it does, but am not confident that my (hasty) reasoning holds up. Here’s the pitch. The extension of the reasoning to the principled right might narrow the gap between Obama and Romney such that universalizing Voter’s calculation would then cost Obama a shot at Kansas’s electoral votes. So even if Russel restricted his reasoning to “safe Romney” states, it still follows that his ability to cast his ballot in good conscience rests on writing off the moral agency of most other voters.

Caveat: I start from a somewhat unsympathetic position. I’m further to the right than Voter; voting my conscience does not mean that I would vote “Green.”

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Instead of “Distance(V-S) > Distance (V-O); and” should you have the inequality going the other way?

Thanks. Fixed. Also added a sentence to clarify things on the third-to-last paragraph.

I think it’s more appropriate to say that objections to voting one’s conscience rely upon the thought that your decision exerts a strong influence on the decisions of others. If lots of other people with similar preferences are voting their conscience, your decision to vote Obama won’t prevent the Green party from spoiling the election. If they’re not, your decision to vote Obama is not needed. The fact that other people might vote their conscience too doesn’t really provide a justification for not doing so yourself, unless you engage in magical thinking about the correlation between your decision and theirs.

It’s of course true that there is some risk of spoiling the election if enough people register protest votes. There’s no getting around that. But the collective response of progressives to Conor’s essay can basically be summed up as “but we want to have our cake and eat it too!” To a first approximation, those members of a party’s coalition who are willing to stay home if they don’t get what they want are precisely the ones who do in fact get what they want.

That’s a very particular (and peculiar) sense of “universalize.” Why not universalize Voter’s behavior by saying: “If everyone voted for Stein, Stein would win”?

Fair point. In this case I am universalizing the logic. Voter isn’t dumb; he knows that for most voters (V-S) > (V-O) and/or (V-O) is < than the conscience cutoff.

But then you’re abandoning universalizability. Once I’m allowed to know what most voters are going to do, then I also know that it’s not actually the case that Obama will “face a large enough defection from the left to jeopardize a reasonably close election. ”

This is the paradox that I think the anti-spoiler arguments all run aground on. They’re universalizability arguments for a non-universal segment of the electorate selected just for purposes of the argument. They treat the individual third-party voter as bearing the moral weight for what-would-happen-if-10%-of-people-did-that without getting the moral credit for what-would-happen-if-everyone[-or-51%]-did-that.

I fully admit that clases of arguments for voting for 3rd party candidates would pass this test. As I said, I’m focusing on a specific line of reasoning.

What “paradox”? Why not ask President Gore how that reasoning goes?

I mean, I know the “President Gore” response is probably tiresome to you, but the consequences of Nader-voting were pretty tiresome to the rest of us.