This is a guest post by Daniel J. Levine (University of Alabama) and Daniel Bertrand Monk (Colgate University). Daniel J. Levine is author of Recovering International Relations: The Promise of Sustainable Critique. Daniel Bertrand Monk is the co-editor, with Jacob Mundy, of the forthcoming: The Post-Conflict Environment: Intervention and Critique (University of Michigan, 2013). The authors’ names for this essay have been listed alphabetically.

tl;dr notice: ~2600 words.

“As Ambassador Gillerman has said many times on our show, ‘Israel lives in a dangerous neighborhood.” — Fox News, 16 November 2012

“As he was asking instructions…a man in his early 20’s came up, stuck the point of a knife against his back and ordered him into the lobby of adjacent building….The youth was…ordered to surrender his money. He explained that the only reason he was there at all was that he had no money…. The man closed his knife and said: “Look, this is a very dangerous neighborhood. You should never come to this part of the city.” Then he instructed him to his destination via the safest route, patted him on the back and sent him on his way.” — New York Times, Metropolitan Diary, Lawrence Van Gelder

The Arab Middle East may have undergone significant political transformations in the period between Israel’s 2008 ‘Cast Lead’ Operation against Gaza and the recent ‘Defensive Pillar’ campaign, but no one in Jerusalem or Tel Aviv appears to think that a review of Israel’s ‘grand strategy’ is warranted. If anything, seasoned observers suggest, the Arab Spring seems to have driven Israelis to assume out of resignation a position which Zionist nationalists like Vladimir Jabotinsky once held with fervor. Writing in 1923, Jabotinsky evocatively described a metaphorical “iron wall” that would protect Zion from the ire of its neighbors; for their part, contemporary Israelis (we are told) can only imagine a future in which they will be perpetually enclosed within a (quasi-literal) Iron Dome. Hence, Ethan Bronner reports: Israelis have concluded that “their dangerous neighborhood is growing still more dangerous…”’ To them “that means not concessions, but being tougher in pursuit of deterrence, and abandoning illusions that a Jewish state will ever be broadly accepted” in the region.

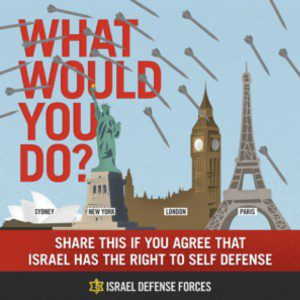

Interpreters of the Israel-Palestine conflict in the ‘Anglosphere’ and seasoned Middle East watchers often resort to the same curious euphemism: seeking to make the region’s unique patterns of violence intelligible to American audiences and to themselves, they explain Israel’s impatience with diplomacy, and its reliance on disproportionate use of force, by referring to the “dangerous neighborhood” in which it finds itself. Bolstered by an “ideology of the offensive” that has been present in Israeli strategic/operational thought since the 1950s (see here, here, and here), and by the ostensible ‘lessons’ of the Shoah for Jewish self-defense, this euphemism evokes positions so pragmatically self-explanatory that no further justification is felt to be needed. The IDF Spokesman’s Unit even released a meme (see the opening image) with the intention of rendering this logic visually explicit.

To be sure, the region is dangerous: Israel has fought three large-scale regional operations since 2006; according to Betselem, 319 Palestinians and 20 Israelis have been killed since the last round of fighting in Gaza – “Operation Cast Lead” – in which almost 1,400 Palestinians and 9 Israelis died. And that’s at the ‘narrow edge’ of the regional violence wedge: in Syria, perhaps 40,000 people have died over the past 12 months, and that civil war has already begun to lap at Israel’s northern border. In Iraq over 100,000 people have been killed since 2003, even before one counts excess mortalities caused by the destruction of its infrastructure. One could go on.

It is, for all that, difficult to escape the impression that this common euphemism of regional instability offers far more blindness than insight into the origins of the current and future violence between Israel and Hamas. In fact, the choice of phrase is itself revealing. To euphemize the awful arena of Israeli/Palestinian rocket fire in terms of a ‘dangerous neighborhood’ is to do several things at once. First, the truism refracts the region’s instability in terms of Israel’s security: no one speaks of ‘dangerous neighborhoods’ as a problem for Palestinians or Jordanians. As the implicit referent of security, the Israel living in a dangerous neighborhood is at once motivated by the need to retain or recover its deterrent capacity, even as it is seemingly exempt from the “security dilemma.” In this sense, contemporary ‘dangerous neighborhood’ chatter is exceptionalist for reasons that were anticipated by Robert Jervis over thirty years ago. “In domestic society,” Jervis explained:

…there are several ways to increase the safety of one’s person and property without endangering others. One can move to a safer neighborhood, put bars on the windows, avoid dark streets, and keep a distance from suspicious-looking characters…but no one save criminals need be alarmed if a person takes them. In international politics, however, one state’s gain in security often inadvertently threatens others.

The point here is not that Israel is somehow acting illegitimately in maximizing its own security. That’s a state’s job, and studies of Israel’s civil-military relations show how assiduously the Israel of a previous era sought to achieve that aim by avoiding triggers to autonomous or inadvertent escalation with its neighbors. But unlike Jervis, contemporary ‘dangerous neighborhood’ euphemists reify the language of domestic society to describe the international arena. In doing so, they substitute causes for effects.

This suggests the second effect of the ‘dangerous neighborhood’ euphemism, and it requires some elaboration. To the middle-aged American ear the term ‘dangerous neighborhood’ carries with it disquieting and overdetermined resonances to mid-century struggles over desegregation and ‘white flight’ from America’s cities. It connects to a racialized “criminalization of poverty” on America’s “mean streets.” The best solution American sociology offered those left behind in “dangerous neighborhoods” was a new theory of “Defensible Space” that served, instead, as a pattern book for further white self segregation in gated communities.

In the same way that the gated community presented itself as a frightened response to such neighborhoods rather than a further development in larger socio-economic process that produced them, so too the self-bastionization of Israel is euphemized as a reasonable reaction to the “dangerous neighborhood” it helped bring into being when it withdrew unilaterally from Gaza, marginalized the Palestinian Authority, and so helped usher a new Hamas-led regime into existence. A less superficial assessment of Operation ‘Defensive Pillar’ would begin with recognition that the real “dangerous neighborhood” is one which includes Israel, and which Israel helps produce.

This is the third – and by far most dangerous – bit of work which euphemisms of the ‘dangerous neighborhood’ variety do. They allow Israeli leaders and their American ‘explainers’ to conceal – first and foremost from themselves – the degree to which Israel’s foreign and security policy vis-à-vis the Palestinians is in fact driven by its own domestic realities; that is, by a political system that is procedurally and ideologically stalemated, a polity that is dissolving, and a state that is – borrowing a phrase from the late Susan Strange – in profound retreat.

This also requires some explanation. Since the early 1990s, Israeli domestic politics has shifted profoundly. Formerly state-owned (and Labor-party controlled) assets and industries were sold, the mass media was liberalized and marketized, and a series of electoral reforms gave the traditional “national” parties a distinct disadvantage vis-à-vis smaller “fractional” movements. A slimmer public sector could no longer be mined for political patronage by traditional power-brokers; single-issue parties proved increasingly adept in using coalition negotiations to wangle political “goods” while economic inequality grew and taboos on ethnic and fractional politics waned. Into this mix also came a slow undoing of the state’s political-security consensus. The first Palestinian intifada and the 1991 Gulf War suggested that continued Israeli presence in the Occupied Territories might be more a strategic liability than an asset.

At the same time, however, constituencies for the occupation within Israel began to coalesce into a new demographic that had little patience for such arguments. The two developments are linked. With a durable Egyptian-Israeli peace, a growing alliance with the US, tacit (if ambiguous) acceptance of Israel’s nuclear deterrent, and a broader decline in Soviet support to Israel’s traditional rivals, the evaporation of actual existential threats itself became an existential threat to those for whom the maintenance of a ‘garrison state’ had become secondary to the task of perpetuating and deepening the occupation: not the order of precedence which Israel’s ‘old school’ security hawks had necessarily intended.

The history of this transformation is too complex to fully delineate here. (See our earlier discussion here; for longer takes, see here and here). But its effects are not: Israel’s political divisions are no longer constituted by the “left/right” ideological divisions familiar to (and taken for granted by) policy intellectuals. The real animating division now lies between statists and radicals: positions in which, respectively, the Israeli state is to be understood as a pragmatic, worldly solution the immediate problem of Jewish statelessness and vulnerability in the modern era on the one hand, and in which the state is understood as a stepping-stone toward some variation of a “Third Kingdom of Israel,” whether parsed through explicitly Messianic terms, or couched in ostensibly secular-nationalist ones, on the other. The former camp accords the state a legitimate claim to popular loyalty and collective action; and it expects citizens to coordinate their personal and collective aspirations with its understanding of the common good. In this sense, they are liberal-nationalists. For the latter – best exemplified by the settlers, but by no means limited to them – the state is a means to an end, and allegiance to it is conditional.

These positions – statist and radical – are not reducible to parties or individuals, though different individuals and parties can more credibly occupy one, the other, or the space between them. The ability to ‘play’ that space, we mean to suggest, has come to constitute the ‘game’ of contemporary Israeli domestic politics. For a variety of reasons, it is most easily exploited by the leaders of the old “right.” Likud’s traditional commitment to the ‘greater Land of Israel’ gives it natural points of connection with the settlers; its historic self-understanding as a movement ostracized from Labor’s good graces give it have natural resonances with the Sephardic Shas and with parties representing immigrants from the former Soviet Union; while the party’s traditional secularism produced leaders (Sharon, Netanyahu) that could ‘wink’ to the party’s liberal wing (nowadays represented by Dan Meridor). It was this flexibility that made Sharon able to carry out the redeployment from Gaza and the northern West Bank, and it allows statists some leverage over the settlers too. Like Charles de Gaulle, Bibi might threaten to ‘break left’ and abandon the settlers the way that de Gaulle abandoned the pieds noirs. A Netanyahu government thus constitutes the most expedient way that each side may continue to hold the other hostage. So long as Likud performs reasonably well in the elections – and a Nate Silver-like aggregation of polls predicts that it will – a continuation of this stalemate/retreat seems assured.

It is impossible to over-emphasize the degree to which the stability that a Netanyahu government promises actually brings with it no freedom of action. The position Netanyahu occupies is secure only so long as he – or anyone else who might climb the ‘greasy pole’ into the premiership – can sustain a studied intransigence on all those positions that pit statists too squarely against radicals. For while the former outnumber the latter quite considerably, the latter have a hidden measure of leverage. Since the Rabin assassination in 1995, radicals have been threatening – and delivering – violent responses to statists when they trespass the boundaries of the status quo too brazenly. The settler-led ‘price tag’ campaign – attacks on Palestinian lives and property in the West Bank and Israel, on IDF military bases, and on leading leftist peace activists and intellectuals – are one face of this. Another is a growing movement among rabbis in the settler community to legitimate disobedience to orders issued to IDF soldiers if those orders involve the ‘uprooting’ of Jewish communities in the West Bank.

Though unspoken, the message is clear: challenging the radicals head-on means civil war for the statists. It was for this reason, we argued last year, that Israel’s June 14 housing protests collapsed. For the protestors and the silent majority of statists to claim the resources needed to revitalize Israel’s waning social democracy, the true costs of occupation and settlement would have had to be taken on, as would the civil conflict that would ensue. Bibi – or anyone else occupying his niche – ‘wins’ only so long as that confrontation can be avoided.

In that context, Operation ‘Defensive Pillar’ reveals a logic that is even grimmer than its leading detractors – like John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt – realize. It is not merely – true though it is – that the fighting will produce deaths without producing a strategic breakthrough for either side. If that were all, reasoned arguments like theirs might somehow still carry the day. In fact, the violence is not pointless. Rather, the point it serves remains unrecognized, because it is internal to Israeli domestic politics. An ongoing, violent stalemate, with the Palestinians, in which a ‘return to the peace process’ is promised but never made good upon, is precisely where the ‘Venn Diagrams’ between the statist position and the radical one overlap, and this is what presents itself to the world as if it were Bibi’s “comfort zone.” To pay lip service to such a process by framing repeated incursions into Gaza as steps forward or backward from that aim permits statists to avoid the reality that with every passing year, the government of Israel is less and less able to summon the political legitimacy needed to negotiate a conclusion to the conflict. Conversely, in protesting against a cease-fire with Hamas, the radicals allow themselves to think that Israel’s limited and periodic incursions into Gaza signal something other than the limit of possible action actually circumscribed by their own precarious balance with the statists.

This final aspect of the ‘dangerous neighborhood’ truism reveals the real tragedy of Operation ‘Defensive Pillar.’ It is not merely that over 160 people have died with more almost certain to come – the overwhelming majority of them Palestinians. Nor is it that those deaths could somehow be avoided by finding a modus vivendi between Hamas and Israel. As Gershon Baskin has indicated, this was in the offing on the eve of ‘Defensive Pillar.’ The tragedy is that these deaths become a means for Israelis, and Israel’s ‘explainers’ abroad, to misconstrue the basic, profound stasis into which that state has fallen for its regional effects – and thus to perpetuate them both. To invoke Israel’s “dangerous neighborhood” is to give priority to the image of a state that once was – but is no more – just as it is to conceal how the actually existing Israeli state’s divisions contribute materially to the dangers to which it appears to be responding. Unless that stasis itself becomes a focus of attention – within Israeli domestic circles, and among external power-brokers – meaningful change is unlikely to come. Instead, the imputed “obviousness” of this conflict, will simply, as Theodor W. Adorno once put it, continue to serve as “an asset to its apologists.”

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Fascinating. The discussion of the ‘constituencies for occupation’ remind me of the way in which colonial adventurers and vested interests pushed Britain into expansion in Africa, even against what it perceived as its own interests. Perhaps not too surprising that the sociology of Israel’s foreign policy is not radically dissimilar to other white settler societies of the past.