This is a guest post by Peter S. Henne. Peter is a doctoral candidate at Georgetown University. He formerly worked as a national security consultant. His research focuses on terrorism and religious conflict; he has also written on the role of faith in US foreign policy. During 2012-2013 he will be a fellow at the Miller Center at the University of Virginia.

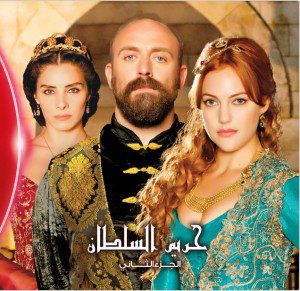

Last December, I was in Doha to attend the UN’s Alliance of Civilizations conference. While fighting off jet lag in my apartment–the 13 hour flight is a killer–I saw a commercial for ‘Hareem al Sultan’ (the Arabic version of the original Turkish name, ‘The Magnificent Century’), a racy-looking soap opera on a UAE TV station. The show depicts the life of Suleiman the Magnificent–one of the greatest Ottoman Sultans–focusing specifically on the women in his life. I was a little surprised to see something that would shock my rural PA hometown’s sensibilities on Middle Eastern TV, but that was the last I thought of the show.

Until this week, when I saw a report that Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan has publicly attacked the show. Erdogan was upset by its depiction of the Sultan–whom he claimed spent more time on horseback than in the palace–and conservative sentiment in Turkey was angered by the show’s risque nature.

This soap opera dispute soon became embroiled in Turkish domestic and international politics, however. Erdogan’s attack on the show came in the context of criticism he has received for Turkey’s recent involvement in Middle Eastern affairs, specifically its support for Syrian rebels. Some of this has to do with the Syrian refugees in Turkey, or the hit to trade as a result of the conflict. Others worry about Turkey’s ability to actually influence the region to the extent that Erdogan desires. Erdogan responded to these critics by referencing Turkey’s Ottoman past, in the process slamming the soap opera. This isn’t the ‘neo-Ottomanism’ feared by Erdogan’s critics (an attempt to recreate the Ottoman Empire), but rather the increasing influence of the Ottoman legacy on Turkish politics after it had been effectively removed following Ataturk’s secularizing reforms of the early twentieth century.

Domestically, it raised concerns about Erdogan’s treatment of the opposition. Erdogan signaled he would call for some sort of legal action against the show, prompting worries from some observers. And one figure from the CHP, the main opposition party, even drew on Ottoman imagery, suggesting Erdogan desired to be the ‘only Sultan’ in Turkey.

Domestically, it raised concerns about Erdogan’s treatment of the opposition. Erdogan signaled he would call for some sort of legal action against the show, prompting worries from some observers. And one figure from the CHP, the main opposition party, even drew on Ottoman imagery, suggesting Erdogan desired to be the ‘only Sultan’ in Turkey.

What is going on? Is a soap opera defining political disputes in Turkey?

Like many who study international relations scholars, my first impulse is to approach culture as instrumental or secondary to political calculations. Indeed, in my own work on religion, I’ve found that religious influences on both United Nations voting (forthcoming in Politics and Religion, see here for a working draft) and interstate conflict depend on the political conditions in which religious beliefs arise. Surely this soap opera and the Ottoman references are just rhetoric designed to mask self-interest?

But there’s a reason why these cultural factors matter, even instrumentally. Attitudes towards the Ottoman Empire resonate strongly in Turkey as an element in Turkish national identity. To some, they should be cherished and celebrated, inspiring contemporary Turkish endeavors. To others, they are a worrisome backsliding from the secular Turkish republic Ataturk created. But even though attitudes towards the Ottoman era are not driving Turkish political opinion, they are a tool through which actors frame their arguments and define their preferences; culture and politics interact, rather than compete. Similarly, while I found in my studies that political conditions filter religious beliefs, it was the religious beliefs that prompted state action in the first place.

So we probably won’t be able to understand Turkish politics by studying its soap operas, and Erdogan is not intervening in Syria because of his admiration for Suleiman the Magnificent. But we also will miss out on a lot of political debates in Turkey–which will likely have a huge impact on the Middle East–without taking the furor over ‘The Magnificent Century’ into consideration.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Led light uses light-emitting diodes (LEDs ) as the light source, have longevity and low energy saving ,also without harmful substances to humen.Though the led lightings’initial purchase costs are more expensive than traditional lamps , in the long time, it is still worthy to buy them.