My Facebook feed filled up this weekend with salutes to veterans. My friends were mostly Americans, and so most of these (indeed, I’d bet all of them) were tributes to U.S. soldiers. For Americans, of course, Sunday was Veterans Day, but for the British and others it was Remembrance Day. Remembrance Day–Armistice Day, as I think of it–is a more fitting holiday than Veterans Day. It asks us to remember something particularly awful and shattering, the war that the United States has largely forgotten: the war that an American president promised would end all wars.

My Facebook feed filled up this weekend with salutes to veterans. My friends were mostly Americans, and so most of these (indeed, I’d bet all of them) were tributes to U.S. soldiers. For Americans, of course, Sunday was Veterans Day, but for the British and others it was Remembrance Day. Remembrance Day–Armistice Day, as I think of it–is a more fitting holiday than Veterans Day. It asks us to remember something particularly awful and shattering, the war that the United States has largely forgotten: the war that an American president promised would end all wars.

Every year at this time, I remember the victims of the First World War–the British and the Americans, the French and the Germans, the Australians and the Serbs, the Russians and the Austrians–but I also remember the way that men’s lives were often squandered by thoughtless, pedantic, and careless generals. Too often, as Siegfried Sassoon predicted, their sacrifice has been turned into an argument for offering new generations of young men (and now women) the opportunity to be remembered in wreath-laying ceremonies. There is something about the spectacle of civilians (particularly in the United States) ritually intoning “Thank you for your service” that seems to miss the more profound solemnity of Remembrance Day. (That said, it seems the poppies have gotten out of hand.)

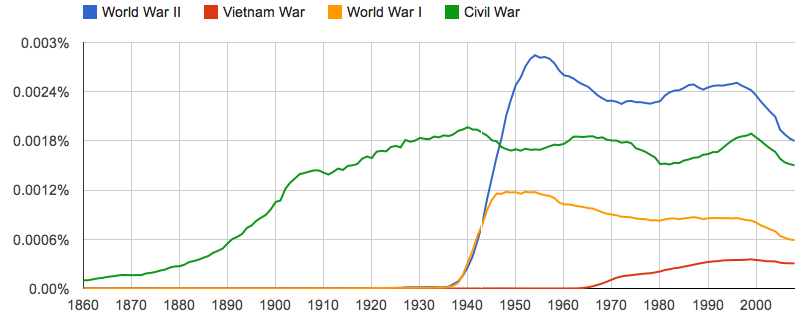

The gulf between Commonwealth and American understandings of war and remembrance is fairly easily depicted. The First World War is all but absent from the U.S. memory and conversation; the Second World War–now probably more than ever the “good” war–dominates, with the Civil War (equally, I would argue, now remembered as a “good” war) maintains a steady beat of support.

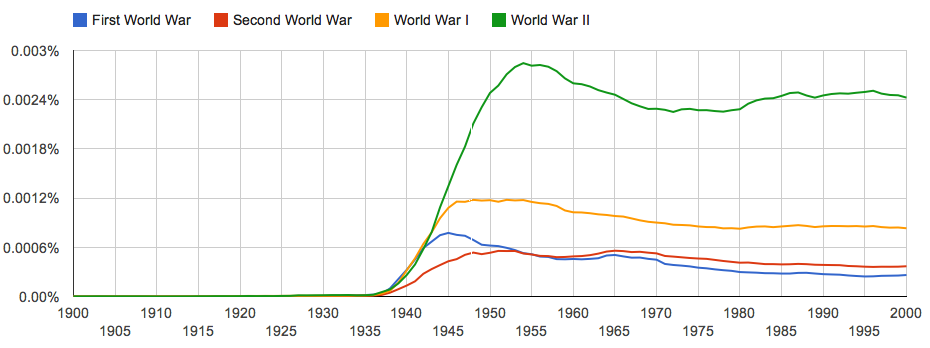

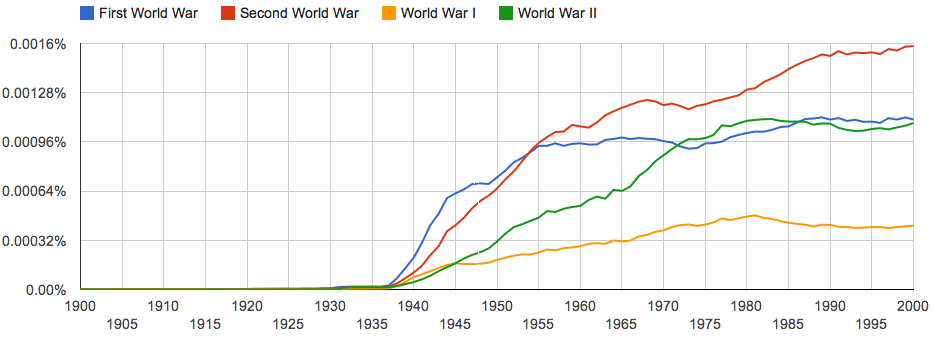

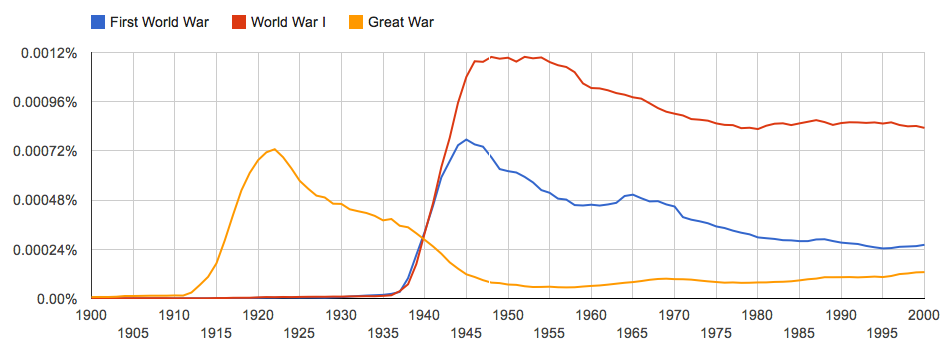

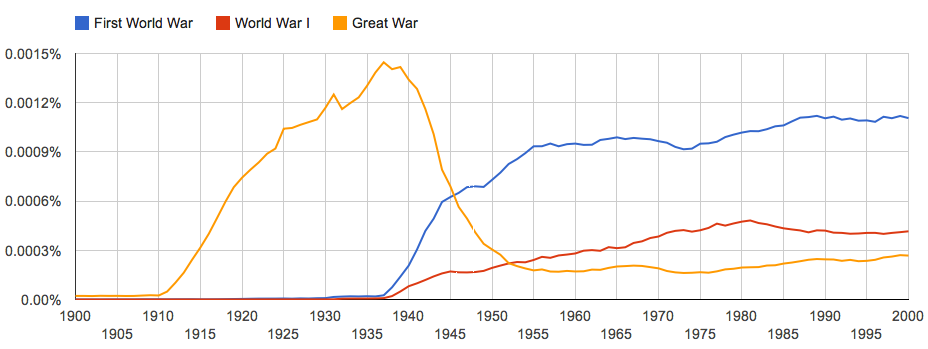

Unsurprisingly, Americans and British use different words for the two global conflicts of the twentieth century (“World War I” and “World War II” for Americans, “First World War” and “Second World War” for British):

What was more striking, however, was how alive the First World War is in Britain and how forgotten it is in the United States. This difference has persisted for a long time. In the interwar period, for instance, the Americans never quite got around to adopting the term “The Great War” while the British only stopped using it when they came to the crushing realization that there was going to be a second.

The Civil War measure does not seem like a good base comparison. Even though ngram is case sensitive, the frequency of Civil War is decidedly non-zero from 1800-1860. Naturally, it does increase quite a bit starting in 1860, however, I am guessing other countries get proper noun Civil War attached after their country’s name. Comparing World War I to American Civil War allows WWI to trump the other.

My guess is that Civil War takes a long time to take off because it probably took a generation or two to kill off “War Between the States” and other competing terms. But “Civil War” has been remarkably steady since about 1910.

1880s were the first public commemorations of the US Civil War and the beginning of the creation of a public memory of the war.

I don’t know exactly how to read the n-grams (w/r/t the vertical axis), but based on the first one in the post, it seems maybe a bit of an overstatement to say that WW1 is “all but absent from the US memory and conversation.”

But you are of course entirely right on the main point about the larger place of the First World War in British (and no doubt French and German and Australian and Serbian etc) collective memory than in American. There were many horrific First World War battles, but the worst single day in the history of the British army was the first day on the Somme (approx 20,000 dead, 40,000 wounded). To find something at all comparable in U.S. history, one has to go back to the bloodiest battles of the Civil War (e.g., Antietam, or Sharpsburg as I think it was called in the South).

Keegan in his The First World War notes that one reason the Br. generals at the Somme had their men walk in straight-up waves rather than having some lie down and give covering fire while the others advanced (I forget the technical term for this) was that the generals thought that once some of the men had gotten prone they wouldn’t get up again (to which my reaction was “well, I definitely wouldn’t have gotten up again”). So instead they sent successive waves of men walking into the German machine guns that the Br. bombardment had failed to eliminate. Keegan ends this section (p.299) with a brief, moving description of visiting “the ribbon of cemeteries that marks the front line of 1 July 1916….”

The vertical axis is the frequency with which the terms are used (as a fraction of Google’s sample of 1 percent of all texts)–it’s expressed in percentages.

I actually don’t think that it’s an exaggeration–or at least not all that much of one. Certainly, we discuss Wilson’s war power exercise much less than FDR or Lincoln’s. But the reasons are exactly those you stated.

“as a fraction of Google’s sample of 1 percent of all texts”

ok, that’s the part I needed explained. thanks.

Sorry, my fault to be unclear in the original post.