It’s that time of year that Dutch people living outside of Dutchland are beginning to hate: the time of Zwarte Piet. To be fair, the feast of Sinterklaas, a holiday that displays none of America’s advanced marketing techniques, was a couple of days ago, but that actually just means that Americans and others have been recently primed to make conversations awkward for their Dutch friends at holiday parties. (This is distinctly different from making awkward conversations at holiday parties, which is a cosmopolitan phenomenon.)

The Dutch may have David Sedaris’s classic monologue Six to Eight Black Men to blame for this, but I’d recommend they sue The Office (the much inferior U.S. version) for damages, since they probably have more money. The Wikipedia page will bring you up to date, but really all you need to know is conveyed by the picture, which I won’t reproduce here because thirty years of anti-racist programming has made me incapable of doing so. (And I was raised in a part of the country where they still read us Brer Rabbit stories in elementary school.)

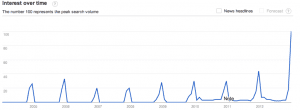

Pity the Dutch all the more, though, since Google News Trends suggest this is going to be the year they have to answer the most questions about Black Peter.

This chart shows both the obvious periodicity (finally a political science time trend with AR(12)!) and the clear increases in searches for the specific term “zwarte piet” on Google in the United States.

Here is a nice response from some Americans living in Amsterdam: https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PL6AAE2F3C3DA802D6&v=HhNdJPntfU8&feature=player_embedded

Talking about Zwarte Piet in my classes about postcolonialism is one of the most profound pleasures as well as fearful experiences ever. Fantastic how critical analysis escalates into trench wars when it hits so close to home base. The discussion of whether Black Pete’s blackness is a symbol of ‘slavery’ or a result of ‘going down the chimney’ is guaranteed to generate open warfare in the classroom. One of the things it shows me is how difficult it is for us to accept that we have traditions and practices that are rooted in racism without directly having to politicise them into ‘for’ or ‘against’ positions.