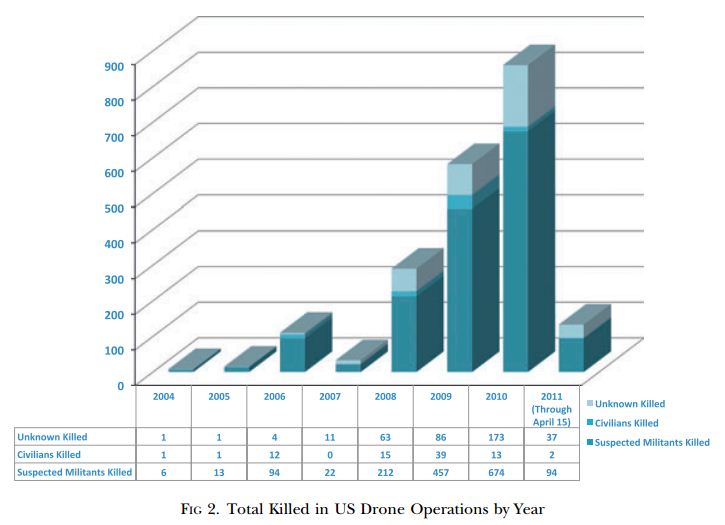

This graph comes to you from a newly published article on the politics of the drone campaign published this week in International Studies Perspectives. I haven’t yet read the full piece so cannot yet comment on it substantively or theoretically. Nor have I looked closely at the authors’ code-book. However based on the abstract, the analysis appears to rest on the empirical evidence of a newly coded dataset (the latest of many out there presuming to calculate the percentage of civilians – v. non-civilians – killed in drone strikes) to make claims about the justifiability of such attacks – presumably by weighing civilian harms against military effectiveness. My reaction here pertains solely to this graph, and what strikes me is the disjuncture between the authors’ coding of “civilians,” and the actual definition of civilians in the 1977 1st Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions.

See for yourself:

Article 50(1):

A civilian is any person who does not belong to one of the categories of persons referred to… in Article 43 of this Protocol…

Hmm, so civilians are anyone not meeting the definition of ‘combatant…’ What might that be…?

Article 43(1):

The armed forces of a Party to a conflict consist of all organized armed forces, groups and units which are under a command responsible to that Party for the conduct of its subordinates, even if that Party is represented by a government or an authority not recognized by an adverse Party. Such armed forces shall be subject to an internal disciplinary system which, inter alia, shall enforce compliance with the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict.

Hmm, so the definition of ‘combatant’ doesn’t include ‘suspected militant,’ therefore ‘suspected militants’ must be civilians unless they meet these criteria…

Article 50(1):

In case of doubt whether a person is a civilian, that person shall be considered to be a civilian.

Hmm, so in addition to many of the ‘suspected militants,’ all those ‘unknowns’ should actually be classified as dead civilians…

Discuss.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

One of the great thing about the conventions is that they are so simple and crystal clear. Nothing but what can be realistically be just in war.

I’d very interested in the legalistic convolutions and contortions made to arrive from that to the result “suspected signature strike target matches disposition matrix parameters”.

I find the entire category of suspected militant a dangerous one. It seems too much like a factor designed to obscure through ambiguity

Quote from the article: ‘Where a person killed was identified explicitly as “Taliban” or a

“foreign fighter,” “militant,” or “suspected militant,” they were

classified simply as “suspected militants.” ‘

This sounds to me as coming close to the US definition of ‘enemy combatants’, though not quite a person “directly participating in hostilities”, to use the ICRC lingo.

The problem is that, under the Obama administration, the definition of “suspected militant” is essentially “Muslim male between 15 and 50 who we don’t definitively know isn’t a militant.” Also, dead Muslims are presumed to be militants unless proven otherwise.

The first problem with this is that there is simply no reliable counting of civilian/combatants – even casualties out there. So it will be interesting to see what “data set” they used.

And – if we’re going to go all API – you mention article 43, but not 44(3)

3. In order to promote the protection of the civilian population from the effects of hostilities, combatants are obliged to distinguish themselves from the civilian population while they are engaged in an attack or in a military operation preparatory to an attack. Recognizing, however, that there are situations in armed conflicts where, owing to the nature of the hostilities an armed combatant cannot so distinguish himself, he shall retain his status as a combatant, provided that, in such situations, he carries his arms openly:

(a) during each military engagement, and

(b) during such time as he is visible to the adversary while he is engaged in a military deployment preceding the launching of an attack in which he is to participate.

In other words, those walking around with weapons are actually often considered combatants in these areas…. depending on your definition of when an ‘armed attack’ begins of course. This gets to the touchy question of DPH – key for this question, but which your post avoids.

Not to mention the fact that combatants are obliged to distinguish themselves from the civilian population – which they don’t do in many of these cases. This, naturally further skews the numbers – but more importantly highlights the rather unethical mode of warfare undertaken by our militant friends who habitually violate the laws of war.