Today is World AIDS Day, an annual opportunity to take stock of the state of the epidemic. Despite a decade of incredible mobilization of finance for and visibility of the AIDS pandemic, UNAIDS estimated that the number of new infections last year 2.5 million still far outstripped the 1.4 million people who received treatment for the first time.

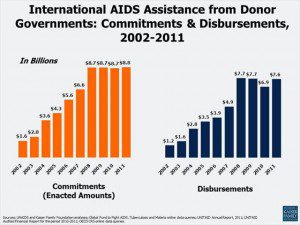

There has been some good news. 8 million of the 15 million people thought sick enough to need treatment now have it, up from 200,000 in the early 2000s. New infections of HIV and deaths from AIDS have dropped significantly in a number of countries. Some like Botswana have even crossed the “tipping point” when those starting treatment exceeds those dying from AIDS. Moreover, the financial crisis notwithstanding, the level of funding to support AIDS treatment remained at high levels. There was a dip in disbursements in 2010 but the drop off was not as steep as some feared.

With new studies that suggest early treatment of AIDS can disrupt the chain of transmission, activists have renewed optimism that an “AIDS free generation,” indeed the “end of AIDS” itself, is possible . They have been emboldened in part because the policy community, after some wavering amidst the financial crisis, has embraced this perspective, as evinced by Secretary Clinton’s World AIDS Day event in which she rolled out the Obama administration’s new PEPFAR Blueprint. Still, I worry that something is amiss, and it’s been a little hard to put my finger on.

- 2012 PEPFAR Blueprint

In the early 1970s, Anthony Downs wrote of the ups and downs (pun intended) of the “issue-attention” cycle. I have a distinct feeling that AIDS is experiencing some degree of issue fatigue.

Part of this is anecdotal. Just a few years ago, HIV/AIDS was a cause célèbre. On campuses like the University of Texas where I work, one could fill a room with earnest undergraduates eager to do something about the problem. For World AIDS day this year, the number of attendees for an excellent event was low. And, to be fair, at this time of the semester, events often have trouble attracting crowds.

Still, I fear that it’s going to be harder to sustain (let alone increase) public attention and resources for this problem in the United States (the major donor for global AIDS efforts) and among other donors, given acute financial problems.

Moreover, should AIDS become distant from the lived experience of people in developed countries, will their publics remain as willing to shoulder a large share of the global burden? (A 2012 poll suggests about 45% of Americans know of someone who had AIDS, died from it, or was HIV positive).

Even though developing countries themselves are increasingly picking up the tab to pay for their own treatment activities, an additional $7 billion per year is needed to expand the number of people on treatment. Amanda Glassman from the Center for Global Development made a convincing case:

…we haven’t yet reached the beginning of the end. There are still 7 million eligible people who don’t receive treatment, 2.5 million new infections every year, and a $7 billion funding gap. And to reach the 2015 goals, 140,000 additional people have to be added to treatment and new HIV infections will have to decrease by 200,000 annually for the next three years.

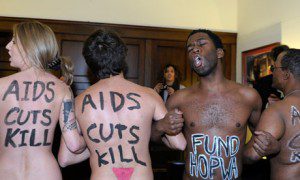

A more imminent challenge at least in America is the fiscal cliff (in Europe it is the fate of the Eurozone). One NGO study estimated that the automatic spending cuts triggered by failure to reach a new budget deal would lead to cuts that would eliminate treatment for more than 275,000 people. This news prompted AIDS activists this week to disrobe in House Speaker John Boehner’s office in a publicity stunt to draw attention to the problem.

One other reason to remain concerned is the state of the primary multilateral instrument for addressing HIV/AIDS — the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. The Global Fund was created in 2002, a relative newcomer to the international landscape, and it is only now coming out of a year long public relations and management nightmare.

One other reason to remain concerned is the state of the primary multilateral instrument for addressing HIV/AIDS — the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. The Global Fund was created in 2002, a relative newcomer to the international landscape, and it is only now coming out of a year long public relations and management nightmare.

In 2011, the revelation that a small amount ($10 to $20 million or so) of the Global Fund’s $20 billion portfolio had been diverted by recipients for corrupt purposes prompted a management crisis at the Fund, including a withering independent committee report, the appointment of a day to day general manager, and the resignation of the executive director Michel Kazatchkine. Donors initially seized up their support for the Fund amidst this turmoil.

After a year steadying the Fund’s once sterling reputation, the Global Fund board just a few weeks ago sought to right the ship by appointing former PEPFAR director Mark Dybul to lead the Fund. It is hoped this appointment along with some other board changes will put to bed a divisive transatlantic dispute that emerged in the wake of Kazatchkine’s departure. Still, aside from raising money, Dr. Dybul is going to have his hands full dealing with a host of tricky issues (like this one on the future of an effort to drive down the cost of malaria drugs).

By most accounts, Dybul is up to the task. He is an openly gay medical doctor who navigated the tough political shoals of the George W. Bush administration to support a massive expansion in ARV treatment access, including the widescale purchase of Indian generic drugs (here is one dissent from Knowledge Ecology International).

Still, it’s going to take all the technical and political skill by Dybul and others to narrow the gap between the ambition to end AIDS and the current state of affairs.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

Nick Wilder,Wheat Ridge, Colorado said”Home Energy Saver helped me save thousands of

dollars per year. It is one government service that makes paying taxes worthwhile.” Xiamen

Mutual Prosperity (MP) Lamp Co.,Ltd products Save money, live better, help the earth!our

products includes : Light Bulbs .

So just what is LED light? In two words, it is the future. It’s the future of both household and commercial lighting. More and more homeowners are giving up their traditional incandescent bulbs and turning to the energy-efficient LED bulbs. Indeed, entire cities and states are trying to benefit the environment by adopting the new lighting technology.

LED Light Bulbs series offer the ultimate in energy saving light bulbs with LED bulbs giving a massive saving of around 90% in comparison to standard filament bulbs with a life expectancy for LED Light bulbs of around 30 times greater.