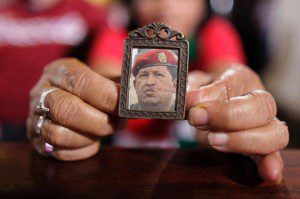

My colleague, Javier Corrales, has an excellent summary of the internal political dynamics in Venezuela on the news yesterday of President Hugo Chavez’s deteriorating health condition. Corrales reports that the “Venezuelan government is busy preparing for the re-inauguration of the country’s beloved president, Hugo Chávez, and also for his funeral.”

The timing of all of this makes for significant confusion:

Venezuela’s constitution offers some guidance on what to do. If the president dies, the vice president (in this case, Nicolás Maduro, an avowed communist) will take office. He will call a new election within 30 days. If Chávez survives but cannot attend the inauguration, most jurists agree that the president of the National Assembly (Diosdado Cabello, who will presumably be reelected to that post in a vote on January 5) will take power. If the government then rules that the president-elect is only “temporarily absent,” Cabello will govern for 90 days, which will be renewable for 90 more. If it instead declares the president-elect to be “permanently absent,” Cabello would be constitutionally obligated to call an early election…

…The political confusion, meanwhile, is no small matter. The government’s unwillingness to accept that Chávez most likely cannot be inaugurated has produced unnecessary uncertainty. The indecision is probably the result of a power struggle within Chávez’s party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. The PSUV knows well that the timing of the announcement of the president’s absence (whether it occurs before or on the inauguration date) and the type of absence (permanent or temporary) determines who gets to control the succession, Maduro or Cabello. And each man leads a different faction.

Chávez stated his preference for Maduro to succeed him in December, during a weekend visit to Caracas between cancer treatments. But the rest of the party does not seem to be fully on board. Maduro’s opponents believe that he is too close to Cuba and too distant from Venezuela. As foreign minister since 2006, Maduro has spent much of his time away from home in recent years. Cabello, too, has detractors. Thanks to his history as a member of the armed forces, a state governor, and a minister of public works, he is seen as being allied with the least glorious element of Venezuela’s revolution: corrupt businessmen and military officials who have profited from their dealings with the state.

Since he was Chavez’s pick, the better money seems to be on a scenario in which Maduro controls the succession. Regardless of who takes control, the situation will be messy. Chavez’s popularity and the infrastructure built to support Chavismo masked a number of lingering problems — high debt, rising inflation, threats to currency valuations, etc…. It will be much more difficult for his (less popular) successor to adjust in the face of competing pressures and promises for more constrained state resources.

More broadly, this raises some interesting questions on the future of the pan-Latin American leftist/socialists movements. Chavez’s anti-imperialist, anti-American rhetoric and his broader socialist populist appeal has helped ignite and inspire left leaning movements and governments in Argentina, Uruguay, Ecuador and Bolivia. How well Venezuela (and Cuba) manage their impending leadership transitions likely will tell us a lot about the future of these pan-Latin American leftist movements after Chavez (and Castro)? Stay tuned….

Jon Western has spent the last fifteen years teaching IR in liberal arts colleges at Mount Holyoke College and the Five Colleges in western Massachusetts. He has an eclectic range of intellectual interests but often writes on international security, U.S. foreign policy, military intervention, and human rights. He occasionally shares his thoughts about professional life in liberal arts colleges. In his spare time he coaches middle school soccer, mentors the local high school robotics team, skis, and sails.

0 Comments