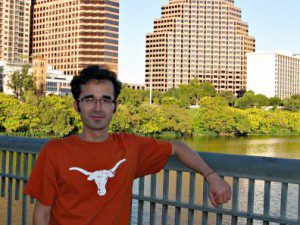

Omid Kokabee is a University of Texas PhD student from the Department of Physics who was arrested in 2011 when he returned home to Iran over the winter break to visit his family.

Omid Kokabee is a University of Texas PhD student from the Department of Physics who was arrested in 2011 when he returned home to Iran over the winter break to visit his family.

Though he is by all accounts apolitical, Omid was sentenced to 10 years for conspiring with foreign governments and given additional time in jail after he earned some money teaching other prisoners foreign languages and physics. His fellow students in the UT Physics Department have launched a campaign to try to free him. They asked my wife, also a political scientist, about what they should do. Can we learn anything from international relations about how to free Omid? What do you think?

First off, we should probably acknowledge that IR theory won’t free Omid. Having said that, maybe something useful can come of what we know about social movements and human rights.

Second, there is a lot about Omid and his research that I don’t know. He studies laser optics, apparently not related to nuclear research, but what the hell do I know about the applicability of laser optics to military-related research? (One reason Omid is in jail may in fact be because he refused to apply his knowledge in ways the Iranian regime wanted).

Third, UT has not yet done a lot to try to help Omid, one of their own students. The UT president has been supportive, but the Board of Regents said the University couldn’t issue a statement and weigh in on such a political matter. To me, that’s an obvious hook for advocacy, but I’m perhaps getting ahead of myself. What can we learn from IR theory?

When Do Social Movements Succeed?

Ten years ago, Richard Price lamented in World Politics that we didn’t really have a good handle on this question. I think we’ve come a bit further since then.

One of the classic formulations about social movements by Doug McAdam, John McCarthy, and Mayer Zald focuses on three dimensions (1) mobilizing resources (what resources movements have), (2) framing processes (what arguments advocates use to represent the problem) , and (3) political opportunities (how open are the opportunities movements have).

I like this work, but it might be a tad vague. Yes, more resources would be nice, having a resonant frame would be fantastic, and sure it would be great to have really favorable political opportunities, but how can we know when these conditions have been met?

In terms of political opportunities, perhaps most important and most difficult for Omid’s case is the extent to which the target is or isn’t vulnerable.

Thinking About Target Vulnerability

Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink in their foundational book Activists Beyond Borders say just a little bit about target vulnerability, suggesting states most susceptible to network pressures are those that “wish to belong to a normative community of nations” (29). Iran at this point hardly looks like it fits that bill.

What’s more, Iran largely lacks other attributes that scholars such as Amanda Murdie and David Davis suggest are needed for successful shaming, namely domestic human rights organizations within the targeted state.

External naming and shaming by the likes of groups like Amnesty International, might have an advantage in autocracies, as Hendrix and Wong argue in a forthcoming piece in the British Journal of Political Science, of making public that which is hidden and largely unknown. Making public human rights abuses, such as trumped up charges against a citizen like Omid Kokabee, might impose political costs on the regime as public perceptions change as abuses are brought light. How regime opponents or even insiders might make political hay out of a situation like this one is hard for me to see.

Keck and Sikkink also suggest that target actors may be vulnerable to material leverage. Indeed, one of the main findings of research on human rights from scholars like Emilie Hafner-Burton is that you can get some compliance pull to support human rights when tied to a source of material leverage like a trade agreement. However, sanctions have yet to bring the Iranian regime to the negotiating table on its nuclear program, and it is a fair bet that no country is going to be that exercised about a single Iranian national being imprisoned that it would impose additional sanctions on top of those that already exist.

The United States does not have significant trade relations with Iran, so negative inducements appear to be out. Indeed, run of the mill abuse of basic freedoms, like imprisoning a PhD student, is unlikely to trigger fears by leaders or their agents that they might be held legally liable for abuses, as they might be if they order or carry out the order to kill political prisoners (this mechanism is identifed by Jacqueline Demeritt in a recent article in International Interactions).

Framing and Normative Appeals

So, if advocates lack potent sources of leverage, what can they do? Keck and Sikkink suggest that framing human rights issues in terms of threats to bodily harm have historically been successful, perhaps because there is some universal recognition that certain practices would be unacceptable if we ourselves were subject to them.

They elaborate by saying that a short causal chain that can clearly establish the relationship between the abuser and the subject is more likely to yield results. What this means in practice is unclear: is it merely that ease of identifying victim and cause helps establish culpability and thereby triggers universal outrage?

In this case, the organizers increasingly have emphasized that Omid is suffering from health problems, and perhaps there is something to be gained by appealing to some universalist notions along these lines. As important as universal appeals may be to generate external support for a cause, one of the main findings of the literature on framing in international relations is the importance of localized messages that resonate within the target state and local decision-makers (see my 2010 book as well Acharya, Sundstrom, among others).

What this means is that organizers need to imagine the conditions under which an internationally isolated Iranian regime would respond to messages from Americans to free one of its own citizens. The campaign has pointed to the successful efforts to free the Alaei brothers, two HIV researchers who were also imprisoned. Why they ultimately were released is a little unclear, but as one news report suggested, one brother credited his U.S. university for its support:

Alaei thanked officials at UAlbany who tirelessly pressed for the brothers’ release and joined Physicians for Human Rights in an international appeal that included rallies in dozens of cities around the world after the brothers’ imprisonment became a cause celebre among the global medical community and at international AIDS conferences they had previously attended.

One of the interesting local features that advocates for the Alaei brothers and Omid have emphasized is that the Iranian regime periodically shows leniency for first-time prisoners by letting them out early, sometimes in time with significant national festivals, like the upcoming March 21st celebration of the Iranian calendar year.

With this in mind, I thought it might be opportune for the international community to appeal for Omid’s release as an act of mercy in light of his medical issues and ask for his release by March 21st.

We Are All Omid

Finally, I was struck by what the University of Albany president said about one of the Alaei brothers in his statement of solidarity and how such a similar statement from the University of Texas president, if he was permitted to make one, might resonate (at least to audiences here at home):

Kamiar Alaei is a member of our university family, and when a family member is in trouble, it is our duty to do what we can to help.

So let’s try that frame out: Omid Kokabee is a member of our university family, and he’s in trouble and needs our help.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

I would be curious to know if there are any business interests or social connections that run through the TX Board of Regents and TX university administration, suggesting their (non)position on this matter reaffirms not an ideology but an interest beyond keeping education purely pedagogical and not political. This poor physics students seems to face tyranny from so many angles.

A couple of points. First thing, is know who you are trying to influence. One thing I have noticed about the Iranian regime is that they seem to be willing to capitulate in public on these types of issues if they can spin it as a magnanimous gesture. Second, I think you hit on the right path with the phrase ’cause celebre’. You have to make the media take interest in this issue, visibility is crucial to mobilizing viral support. Just emphasizing how poorly this guy has been treated is not sufficient. Ideally he would have left a family in the US, a pregnant girlfriend would help a lot. Then you have a narrative that media can tap into and generate an emotional response- reuniting is great political drama.

>”Can we learn anything from international relations about how to free Omid?”

Our nation has a long history of publicly denouncing Iran in the media while secretly negotiating behind the scenes. If you can’t remember Iran-Contra, then perhaps you can remember just where Hillary got her concussion. It is no wonder that Iranians don’t believe the public message coming from the US. It would not surprise me that he is merely another pawn in some political battle – perhaps between the US and Iran, but more likely between 2 competing Iranian factions.

One of the things that many folks don’t understand is that the Iranian government does not accept that you can lose your Iranian citizenship by becoming a citizen elsewhere. Probably one of the more poignant reminders is what appears in the records of the agency that handles security clearances in the US. From just one random sample:

>The State Department continues to warn U.S. citizens to consider carefully the risks of travel to Iran. U.S. citizens who were born in Iran and the children of Iranian citizens, even those without Iranian passports who do not consider themselves Iranian, are considered Iranian citizens by Iranian authorities, since Iran does not recognize dual citizenship. Therefore, despite the fact that these individuals hold U.S. citizenship, under Iranian law, they must enter and exit Iran on an Iranian passport, unless the Iranian government has recognized a formal renunciation or loss of Iranian citizenship. U.S.-Iranian dual nationals have been denied permission to enter/depart Iran using their U.S. passport; they even had their U.S. passports confiscated upon arrival or departure. U.S.-Iranian dual citizens have been detained and harassed by the Iranian government. Iranian security personnel may place foreign visitors under surveillance. Hotel rooms, telephones and fax machines may be monitored, and personal possessions in hotel rooms may be searched.

https://www.dod.mil/dodgc/doha/industrial/12-02878.h1.pdf

Iran is messed up.