I was part of a short conversation last night about the standard job-search process in political science. For those of you who aren’t political scientists, but nonetheless feel compelled to read this, the process for junior candidates looks something like this:

- Starting in the late summer, political-science departments post position announcements with the American Political Science Association. Most job hunters read those announcements on e-jobs and decide whether or not to apply.

- Prospective hires send in materials to institutions. These typically include: (1) at least one writing sample — sometimes a published article, sometimes an article-in-process, and sometimes dissertation or book materials; (2) three letters of recommendation; (3) an application letter detailing why the committee should hire you; (4) a curriculum vitate [CV]; and sometimes (5) a graduate transcript. Some institutions will also ask for an undergraduate transcript, and some will only ask for contacts should they seek letters of recommendation.

- Committees, often composed of 3-5 faculty members, read [the meaning of “read” may vary] those applications and winnow the field down. They may produce a “long short list” of, typically, 6-10 candidates who they are interested in. They may jump directly to the “short list” of, in general, 3-5 candidates who they want to bring in for interviews. Some kind of oversight may or may not follow. Prospective Interviewees are contacted and asked to visit campus.

- The campus visit takes place over 1-2 days. The candidate meets with various faculty, administrators, and graduate students. Meals, including a dinner, take place. Candidate gives ~45 minute job talk with a question-and-answer period.

At liberal arts colleges, of course, (1) the meeting with graduate students is replaced by (often multiple) meetings with undergraduates and (2) the research presentation is either supplemented or substituted with a teaching presentation to undergraduates. Telecommunications interviews may occur at any stage of the winnowing process. Some schools also conduct interviews at APSA. I don’t know much about the two-year college process. Otherwise, YMMV.

The rest of my comments will focus on the typical research-university process. Bottom line: it is a pretty terrible way to evaluate candidates. The worst part is the job talk, which is an extremely artificial exercise bearing little resemblance to most of the professional activity of political scientists. Contemporary justifications for this strange institution are, at best, rather strained. They include that it:

- Provides information about the quality of the candidate as a teacher that couldn’t, apparently, be gleaned from teaching evaluations, having the candidate interact with students, or asking the candidate to teach one or more classes;

- Demonstrates the quality of the candidate’s research in ways superior to reading the research and holding a proseminar (or intensive one-on-one discussions) about it;

- Reveals the ability of a candidate to ‘think on her feet’ — a quality not only of critical importance for a future colleague but also best signaled in the context of a carefully prepared presentation; and

- Weeds out fragile egos and sociopaths (I kid you not).

How important is the job talk? According to one grad-student advice message:

THE “JOB TALK” is perhaps the single most important thing you’ll do during an academic interview. On the basis of your presentation, you’ll be evaluated as a scholar, teacher and potential colleague. A dynamic talk is likely to result in a job offer, while a poorly organized, flat or uninspired presentation will almost certainly eliminate you from consideration.

A “Career Advice” column at Science Careers notes:**

In summary, the job talk is the most important part of the interview process. You were chosen for the interview because of your science and experience, so there is little reason to be very nervous. Practice your talk in front of your advisor, other faculty, and/or fellow fellows so that you can get direct feedback.

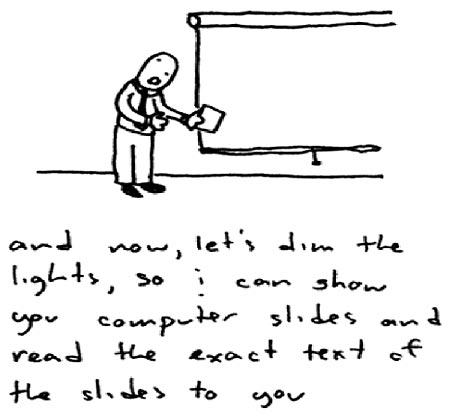

In fact, the job talk is most useful for… assessing the ability of a candidate to give a job talk. The reason we place so much weight on it * is that most academics (and I include myself in this category) are too damn lazy pressed for time to skim carefully read candidates’ portfolios. And why should we? It isn’t like there’s a good chance that the person we hire will become lifetime colleagues… Doh!

I’ve heard rumors of other, more rationale systems. Some say that the University of Chicago conducts an intensive proseminar in which the candidate provides introductory remarks and then everyone discusses an article-length piece of research. This strikes me as a plausible alternative to the modal job talk. But I ask our readers: are there others? And does anyone want to defend the status quo?

*This is not necessarily the case for senior job candidates, whose talks almost invariably stink (actually, most job talks stink, period). A fact that those who oppose the candidate will just happen to forget during hiring deliberations, and will therefore take as evidence that her accumulated record is irrelevant and/or that she wasn’t showing respect for the Department.

**The same column makes clear how mind-numbingly formulaic job talks are, e.g., “Job talks have a specific order.”

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

From my experience on the market, it is more common for there to be a teaching demonstration than a research talk at non-PhD-granting departments, although I have been asked to do both as part of an interview. The teaching demo has its own issues (parachuting into the middle of someone else’s class is never fun, and often times you’re not even parachuting into a real class; it probably favors people who are natural lecturers over people who want to engage in discussion, because there’s rarely any assumption the students have read anything beforehand; different candidates typically prep a different topic, since they’re not on campus at the exact same time teaching the same exact class; etc.). But it probably at least is more reflective of what the average faculty member is expected to do on a daily basis than the job talk, particularly at institutions where the threshold for tenure on teaching is higher than “shows up for class most of the time and students haven’t yet set fire to the quad in protest.”

I think like most parts of the process the job talk (and, for that matter, the teaching demo) is more of an opportunity to screw up than an opportunity to shine. It can lose you the job, but as far as I know, from being on both sides of the process, it’s never actually gotten anyone one.

Incidentally, as far as I can tell based on my own experience, the only way to get an offer for a tenure-track job is if someone on the committee either (a) knows you personally or (b) knows a letter writer for you personally. So maybe we should just go back to the 1970s approach of hiring based on “good-ole-boy” networks (perhaps in a more gender-and-race-inclusive way) and get rid of all the window dressing around it.

Sorry Daniel, UChicago has relatively normal job talks. Sounds like you’re referring to our workshop system. I would actually prefer the PIPES model for job talks myself though.

Oh, well. Note I was very careful with my phrasing.

But you hit on a great point that is par-for-the-course at UChicago’s workshops that doesn’t seem standard elsewhere and NO one adopts for job talks: put together an audience that has actually READ an article-length piece that will serve as the focal point of the talk. That way, presentation can be kept to a minimum (as you note, our PIPES intros ideally tend toward the 10-15 minute end) and less time can be wasted transmitting and more can be spent actually engaging. This requires people to actually read the thing before a talk, though, and as you’ve said elsewhere academics don’t actually read each other’s work all that much.

I agree with most od what you say, but in thinking about this from the point of view of the candidate is that the job interview is fairly standardized and that has its benefits in that the candidate has some inkling of what to expect.

I thought the point of it was hazing.

British system has all the candidates in at the same time and they parade the candidates in front of the selection committee and then the results are known within a matter of days since the committee has a chance to see all the candidates in a couple of days rather than drawn out over a semester. I can’t recall if the job talk features here. Maybe something exceptionally short. I recall from friends who have gone through the process that the most discomfiting aspect is going to dinner with all the other prospective candidates so you can size up the field and your chances.

On a slightly different note, different fields have their own mores for talks. Not sure if this is true of job talks but economists tend not to let the presenter get all their material out but interrupt the speaker from the opening salvo.

Our talks at the LBJ School tend to be an hour, inclusive of questions, which is much shorter than what I was accustomed to at Georgetown. I can’t say that any of these ideas strike me as improvements over the present system, as cattle call, Crossfire, and job talk/Q&A-in-an-hour-or-less may be worse than the present system.

One other thing. A pressure job talk is perhaps no less a test of what an academic usually does than is a comprehensive exam. Rarely are we ever tested to write down everything we know about a topic over 8 hours with no notes, and though some programs have moved to take-home comps or shorter comps, I’m not sure if I see a large clamor for getting rid of that system.

A job talk reveals something about the ability of the candidate to convey their research in terms that a smart, diverse audience can find accessible and interesting. It is an art form that may be says little about the person’s scholarship but should tell if they are likely to be a terrible presenter at conferences and possibly in the classroom. The problem is that the candidate could have an impressive list of publications, high teaching evals, great meetings with students and faculty, and flame out on the job talk and not get the job. That happens more often than not. Is that a problem of the weight we attach to the hour plus session? Or, are we actually inferring something fundamental about the candidates’ ultimate unworthiness if they cannot adequately present their work in public?

I find it interesting that most of the discussion I’ve had about this — with smart people — seems to proceed in isolation from the actual post I wrote, e.g., I directly address the “proxy for teaching” argument. And my objection to that is rooted in what I find so frustrating about these discussions: they trot out various folk arguments in favor of the current job talk system without any real reflection about the central information that’s supposed to guide hiring decisions. I mean, how much do we really care about someone’s ability to present at a conference? And if we did, why not adopt 15 minute talks in too-cold rooms with multiple presenters? And this is a skill that we can workshop after we hire.

This comes back to my fundamental concern: at most institutions these decisions likely saddle us with lifetime colleagues, yet faculty outside of the committee invest little time in getting good information about the hire. In the status quo, the job talk takes on enormous importance (possibly for this reason) yet there’s no reason to think it is a terribly good option for providing the info we need.

I’m apparently going to be the lone voice here, but I think the job talk is the best means of achieving the aims we value. I’m assuming these aims include evaluation of the candidate’s research *and*, importantly, departmental involvement in the hiring of candidates. Admittedly, it’d be great if everyone did a careful reading of the applicant’s file … but we can’t get people to do that for reviews of existing colleagues, so we’re definitely not going to get that for multiple job candidates (particularly in situations where multiple lines are open).

I think folks are being too dismissive about what job talks show us. Structuring a talk should, conceivably, bear some relationship to structuring a paper. If a candidate is not able to lay out a puzzle, an argument, and what’s at stake in a job talk, then I would have doubts about her ability to do so on paper. Some people are awful presenters, but one can still see the skeleton of a good talk (if it’s there). But what’s much more important is the involvement of the broader department in the process of hiring, which would simply not occur without the job talk. There are departments in which faculty defer entirely to the committee, and there are departments where individuals outside the committee (and indeed outside the subfield) come to meetings with substantive responses and opinions on the candidate’s work. The latter are better, without a doubt. Not just because broader involvement results in better hiring decisions (though I think it does) but because it results in more cohesive, collegial, supportive, and research-oriented departments.

… And some of my favorite grad student memories were when really smart folks would react to job talks way outside their field. Let’s remember that job talks are one of the few opportunities for cross-field discussion that remain in our discipline.

Josh mentions the UK system, which I have some familiarity with. Yes, there are shorter job talks, and these are sometimes followed by a roundtable or more informal discussion of research with the hiring committee. But it’s really important to underline that the unreformed UK system does not yield good outcomes. In many cases, non-committee members, including other faculty in the department, are not welcome at job talks, and departmental deliberation is not part of hires. As it is here, I’ve more often heard of job talks hurting candidates than helping them … and, if you have only 15 minutes, first impressions have to play a larger role in evaluation (and there are likely gender and race dimensions at work as well). The bigger issue is the lack of department involvement / voting and how that affects departmental cohesion, etc. My sense is that some places in the UK are moving toward the American culture of job talks in order to avoid some of the problems that surface in other places. And hopefully that is sufficiently vague.

In my limited experience as a candidate and PhD observer, the UK talks are indeed much shorter, but the audience varies–could be just the committee, could be all staff, could be all staff and PhDs (it’s worth asking ahead of time who’s been invited since this makes for some significant variation in your audience size). In all the job talks I’ve attended, there was a significant staff presence. Also, the hiring committee wields by far the most power, but there is often a room-wide discussion after each talk where staff members are polled on whether the candidate is ‘appointable’–a kind of half (or maybe quarter) loaf of deliberation. Finally, although shorter and much less like an in-depth seminar or teaching demo, the UK talk still requires a very similar structure: introduce puzzle, lay out (much briefer) argument, present some payoffs.

(Sorry hit send by accident). I agree with Adrienne though that the shorter format prevents the kind of rewarding cross-field engagement that you might get in a longer and more in-depth presentation. As for the candidates’ dinner, as long as you aren’t the *most* awkward candidate there…

I think there just may be a lot more variation in the UK than in the US, where the process (as Dan points out) is really standardized. Even within the one institution I know quite well (Oxford), you’ll have some searches in which you see the kind of informal discussion you mention, while others have job talks that are closed to all but the selection committee. My point was that, at many UK universities, there does not exist a norm that most faculty (or most research-active faculty) should attend job talks.

Here is my dissenting opinion, published about 4 years ago (https://www.waronsacredgrounds.com/uploads/Trial_by_Fire.pdf). In brief, I argue that the job talk is a red herring: it’s all about the Q&A and the 1-on-1s. The disconnect between the stated purposes of the interview processes and our needs covers up the fact that we cannot admit the true purpose of the interview: to find a pleasant colleague to work with. Since that is (sadly?) perceived as a goal unworthy of an academic search, we mask the process with a ridiculous rigmarole.

Ron, the link is broken?

Someone’s added an unnecessary parentheses at the end. I swear it wasn’t me. Here’s one that works: https://www.waronsacredgrounds.com/uploads/Trial_by_Fire.pdf

As a faculty member in the visual arts, our needs may be different–but the campus visit and talk are important in terms of 1) teaching–how someone discusses their own work –and in many cases presents student work–gives a sense of how that person approaches teaching. 2) having just reviewed 48 application packets (in my field this includes reviewing 40 slides plus actually doing all of the reading), not being on the conference interviews (18 of them), I like seeing more work, and hearing the person expand on their written materials. I feel I can make a better decision with more information. 3) It’s good for the students to see the speaker. It’s not fair but with limited budgets its a great way to get more visiting lectures–and we are paying for the visit so I don’t feel we are exploiting our candidate much. 4) It’s only one part of the on-site interview, so a candidate doesn’t live or die on just one element of the interview.