I am happy to invite my friend Tom Nichols to guest-post about the continuing Iraq War debate. Tom responded so substantially to my original post series on the war (one, two, three), that I invited him to provide a longer write-up. Tom is a professor of national security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College and an adjunct professor in the Harvard Extension School. His blog can be found here, his twitter here. His opinions of course are his own, so whenever he says I’m wrong, you probably shouldn’t listen… REK

I am happy to invite my friend Tom Nichols to guest-post about the continuing Iraq War debate. Tom responded so substantially to my original post series on the war (one, two, three), that I invited him to provide a longer write-up. Tom is a professor of national security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College and an adjunct professor in the Harvard Extension School. His blog can be found here, his twitter here. His opinions of course are his own, so whenever he says I’m wrong, you probably shouldn’t listen… REK

I’ve been reading Bob’s thoughts – cogent as always – on the tenth anniversary of the Iraq War. I reject Bob’s exploration of the “culpability” of the IR field for providing any kind of intellectual infrastructure for the war, mostly because I don’t think anyone in Washington, then or now, listens to us, and for good reason. Joe Nye long ago lamented that lack of influence elsewhere, and others agree (by “others” I mean “me”). So I won’t rehearse it here.

Bob and I sort of agree that the outcome of the war doesn’t say much about the prescience of at least some of the war’s opponents: there were people whose default position was almost any exercise of U.S. power is likely to be bad, and they don’t get points for being right by accident.But Bob’s right to make the far more important point about what we do “if we knew then what we know now.” I’m not as sure as he is that there was ever a “neo-con theory of the war,” which I think grants too much coherence to Bush’s advisors. But he zeroes in on the key question: what, if any, arguments at this point can be mustered to defend the war?

After reading the various pieces here and thinking about Bob’s iterations of the discussion, here’s what I really think about Bob’s question on the tenth anniversary of the Iraq War:

I think it’s too soon.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I don’t mean it’s “too soon” to start sorting out the damage. Actually, the sooner we do that, the better. There’s a lot to learn from the war, and some of those lessons – especially about planning, dysfunctional civil-military relations, the dangers of script-writing an invasion, and the hazards of half-baked notions about “military transformation” – are already clear and should be incorporated into our thinking about national security.

I also don’t mean “too soon” in terms of drawing historical lessons – although I think it’s too soon for that, as well. I don’t think we know, really, anything about the long-term outcome of the war and its effect on either the Middle East or the world. That whole exercise, in which people who should know better confidently explain “What It All Means,” is pure nonsense. (Sadly, I said a lot of dumb things at the time, too. Guilty.)

IR scholars don’t need to be reminded that wars have unforeseeable consequences that can take a long, long time to coalesce. Seriously: imagine talking about the outcome of the Korean War a decade after its end. Truman left office with an approval rating measured in scientific notation. We replaced him with a four-star general after a national flirtation with Douglas MacArthur, whom history should revile more than it does. By 1963, “counter-insurgency” and “limited war” are all the rage. And really, it’s not like we’ll end up staying on the Korean peninsula for another fifty years or anything…

Or imagine reassessing Vietnam in 1985, ten years after the fall of Saigon. The United States is only just back on its feet after a crushing recession and a surge in Soviet power in the late 1970s. Who could deny that Vietnam was a miserable failure, a distraction and a foolish waste of resources? After all, the whole thing was really just a nationalist struggle that we misinterpreted as a communist coalition war, wasn’t it?

Now fast-forward after twenty years, to 1995. Now, the Soviet Union…wait, there isn’t a Soviet Union. Revelations from Moscow, Beijing, and Hanoi are just beginning to tell us an ugly story, one that involves words like “domino” and “theory” that no one would have taken seriously even twenty years earlier. Books like Michael Lind’s volume start appearing, in which Vietnam is called the Cold War’s “Dunkirk,” and the shouting starts all over again and hasn’t stopped since.

Let’s also admit there’s a dishonesty in all these “was it worth it?” discussions. There’s no adequate calculus for the measure of a human life; no one should look a grieving parent in the eye and say these wars, any of them, were worth it.

But again, none of this is why I think it’s too soon to talk about the war.

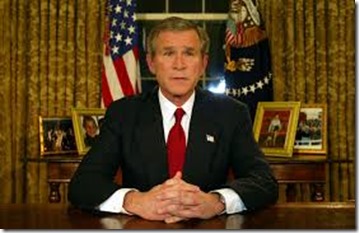

The real reason it’s “too soon” is that many American liberals and American academics (not always the same group, I grant) still cannot think rationally about the war because they still cannot let go of their desire for revenge on George W. Bush.

Sadly, this obsession with Bush really has far less to do with the war per se than with an overall burning hatred harbored by intellectuals for the 43rd president. So while I commend Bob for his calmness and his attempt to find some kind of path to a rational discussion here, I think that there still aren’t many people who are willing to think about this beyond their emotional reactions to Bush (I can think of the exceptions, like NDU’s Joe Collins and his sobering 2008 report, and count them on one or two hands).

Just look at some of the stuff that’s been published on the occasion of the anniversary by Bush’s critics, and you’ll see what I mean. All of it is aimed not so much at a consideration of Bob’s question – especially whether there was a good reason to go to war – but more at a furious attempt to hang everyone involved.

Gawker.com, for example, claimed to have hacked Bush’s personal email and invited people to “wish George Bush a Happy Iraq War Day.” The usual suspects – let’s just use Michael Moore, because he’s predictable – claimed that Bush basically got away with “murder,” and should be in jail.

But even people with intelligence and wisdom lose their perspective when talking about Bush and his coterie. Consider Andy Bacevich’s recent piece in Harper’s, where he taunts Paul Wolfowitz about writing a memoir. The piece is one of Bacevich’s best: there are a few people out there whose writing not only inspires me, but also provokes my envy at their skill. Andy is one of them.

That skill, however, doesn’t hide the fact that Bacevich doesn’t really want to have a discussion about the war. He wants Paul Wolfowitz – and pretty much everyone else involved in the war – to go before the American people, fall on their knees, and beg for mercy:

To be sure, whatever you might choose to say, you’ll be vilified, as Robert McNamara was vilifed when he broke his long silence and admitted that he’d been “wrong, terribly wrong” about Vietnam. But help us learn the lessons of Iraq so that we might extract from it something of value in return for all the sacrifices made there.

Forgive me for saying so, but you owe it to your country.

Give it a shot.

Well, who wouldn’t be inspired to write an honest and introspective book after that warning, which amounts to a demand not for a memoir, but for a confession? It’s like Brian Dennehy’s line in the classic movie Silverado, when he tells a captured man not to worry: “We’re going to give you a fair trial, and then a first-class hangin’.”

I’ve singled out Bacevich’s piece, paradoxically, because it’s good. It’s a great read. But the tone is pure acid – as are so many of the other “analyses” of the war.

This isn’t the place to go into why liberals hate Bush so much. That they do, and that they will violate even basic norms of intellectual inquiry when discussing his presidency, is beyond dispute. My colleague Steve Knott has written a devastating book whose title says it all: Rush to Judgment. Knott documented how presidential historians essentially discarded any scholarly standards in trying to assess the Bush presidency even before it was over.

More recently, Steve did a piece in the Wall Street Journal pointing out that there was a time when almost everyone on the planet agreed that there were WMD in Iraq. (He also tells a great story about how someone in the Clinton administration, likely Madeleine Albright, wanted to engineer a military crisis with Iraq. How soon we forget.) Steve tells me that he has gotten hate mail for that piece like he’s never seen before. He’s a little surprised. I’m not.

My own theory is that intellectuals hated Bush not for what he did, but for who he was. Specifically, they hated him because he didn’t care about them. It’s important to remember that many people espouse politics as a form of self-actualization: they choose political positions based on what they think those positions say about themselves to others: “I support Obamacare because I love the poor, and that makes me a good person, and certainly a better person than you,” or “I hate gay marriage because Jesus loves me more than you and I’m going to Heaven.” Sanctimony is always the dread companion of political conviction.

Bush, in going to war, clearly didn’t care what a group of professors wanted, or what they said in a New York Times full-page ad. That whole thing, in fact, reminded me of a story I heard about Jesse Helms, which I could swear was printed somewhere back in the ‘90s, so maybe it’s not apocryphal. The short version is that some staffer came in all in a lather because the Times had, as usual, dumped on Helms, and the kid wanted to write a rebuttal. Helms said: “Well, son, that’s just fine, and you go ahead and do that, but I have to tell you: I don’t read the New York Times. And nobody I know reads the New York Times.”

If you want to piss off the New York Times and the people who adore it, that’s the quickest way to do it, because it says to them the one thing they cannot bear: You did not matter in this decision. And until those psychic wounds heal, a lot of people are going to carry just too much baggage into this discussion.

Still, Bob asked a real question, so at the end here, I’ll answer it.

I supported the war, just as I supported the 1991 war. (I drafted Senator John Heinz’s floor statement explaining his vote in that one.) I supported regime change in Iraq as early as 1994. Like most people, I thought we had done our job after kicking Saddam out of Kuwait. I underestimated his staying power, and I thought soon after the end of that first war that we had any number of reasons to go back to war, including Saddam’s plot to kill the first President Bush, his attempt to exterminate the Marsh Arabs, and his repeated violations of the UN cease-fire resolution.

Nonetheless, we screwed up the execution beyond belief. I have spent ten years in classrooms with many of the men and women who saw it first-hand, some of whom paid dearly for the arrogance of Rumsfeld and others. I am continually stunned by what I hear, and I can only agree with Ambassador Barbara Bodine, who often said: “There were 500 ways to do it wrong, and two or three ways to do it right. What I we didn’t understand was that we were going to go through all 500.”

That doesn’t mean I think the war was immoral, criminal, or based on lies. I think lives, American, Allied, and Iraqi, were recklessly thrown away, just as they were in the horrendous island-hopping campaign in the Pacific in World War II, as they were in the push to the Chinese border in Korea, as they were every day in Vietnam.

But unlike a lot of my colleagues, I don’t think I know what the war “means” just yet. And I’m not ready to convene any kangaroo courts: not for Bush, not for his advisors, not for the media, not for the academy, nor for anyone else.

At least not yet.

Cross-posted at Asian Security Blog.

Associate Professor of International Relations in the Department of Political Science and Diplomacy, Pusan National University, Korea

Home Website: https://AsianSecurityBlog.wordpress.com/

Twitter: @Robert_E_Kelly

How do you so cleanly dis-associate ‘who Bush was’ from ‘what he did’? Are you arguing that there was no inter-relationship between his actions and how his character was judged? That when individuals came to their emotional distaste for the man, that his actions did not play into that? Are you claiming that there is no link between his disdain for a particular group of people (with expertise in precisely the area we most needed expertise and debate in at the time, given the issues facing us) and the conduct of national debate (or lack thereof) during his tenure? Maybe i am not understanding your point, but i just do not see any sort of clean delineation between character and action here. Say what you want about the constraints on presidential power and such, but its hard to argue that the man was completely bereft of agency such that his actions speak not a word about his character.

This claim that it is ‘too soon’ to debate these issues is equally problematic. Constructive debate is a process, one which involves, if not necessitates, a lot of people being wrong and speaking before all the facts are in. That is how the discussion moves forward. People make claims, often time too hastily. Others make counter claims. The debate progresses. Asking the academic community to refrain until ‘all the facts are in’ or whatever is doubly problematic. First – it advises that community to only further isolate itself by not speaking to the problems which the majority of people are concerned about, asking them to be actively complicit in their marginalization. Secondly – when do we ever have all the facts? How do we ever know if the time is ripe. There is always the possibility that there is another revelation just on the horizon. Pardon me, but i am not going to be holding my breath.

This piece seems just as animated by a personal grudge as much as any of the examples you are speaking to. For instance – you claim that ” there’s a dishonesty in all these “was it worth it?” discussions “. What is this ‘dishonesty’ you are speaking about – and how can you be so sure about reading the motivations of those asking those questions from their writings, yet at the same time be cautioning your interlocutors not to muddle their personal appraisals of the character of their opponent (Bush) with their political/scholarly judgments about their actions? Not an outright contradiction, sure, but forgive me if it raises my hackles a bit.

But if you want to talk contradictions – lets look deeper. You start with this gem, referring to those who react negatively to all uses of US power [as if taking that position inherently precludes the possibility that anyone could have arrived at the conclusion through a rational processes] You state – ” they don’t get points for being right by accident. ”

Aside from the fact that characterizing your opponents here as keeping score – which is a charge of callousness to the highest degree – you end up, later in your essay here, doing just this – giving some people ‘points’ for accidentally being right. I am pointing to your paragraph where you discuss how “Revelations from Moscow, Beijing, and Hanoi are just beginning to tell us an ugly story, one that involves words like “domino” and “theory” that no one would have taken seriously even twenty years earlier. ” When i read this, it sounds like you are implicitly lauding those who used those justifications originally – ignoring your own admonition not to give ‘points’ to those who were proven ‘accidentally right’ a generation or two after its all over. While that was not your point with that statement, the inconsistency is still there. [as you are in this paragraph implicitly contending that the public disdain for the architects for that war came too soon, as they were later to be exonerated by some set of facts which they could not have known about at the time…]

But aside from all of the specious arguments – i disagree with the basic premise here. No, rather than waiting on the sidelines, i think that the IR academics – those purported experts – have an obligation to be actively involved in these discussions, even when they don’t quite know the full historical consequences. And i don;t think you can so readily fault those commentators whose political judgements intermix with personal ones. They are necessarily intermixed. People evaluate character based upon actions, and actions based upon character. Its a dynamic relationship, and separating which is prior seems pretty futile. People don’t merely support policies as a badge of honor – most of the time they actually believe that, say, OBamacare is good for the poor. Sure, they like to tout the fact that they care about the poor, but when they judge someone as not caring for the poor b/c they disapprove of Obamacare, the whole part where they hold |Obamacare=good for the poor| is pretty central to that whole process. Rather than loudly trumpeting moral high ground political position A, then going on to vote with secret ballot for position B, we actually see people carrying these badges of political honor all the way to the ballot box. For all the hubub in the past 2 presidential elections about the supposed ‘Bradley Effect’ and all that jazz, well, the ‘louder’ polling data turned out to actually be UNDER estimating the ‘quieter’ political sympathies which emerged in November.

There was certainly a large part of the Iraq War debate which was driven by resentment and personal attacks. I just find it hard to swallow that it is the IR community who was driving, or responsible for, this aspect of it. In a threatening environment, observers try to read motivations into most actions, and even defensive maneuvers will appear as offense.

Your long post tells a short story: At the very outset, you do not distinguish between Bush personally and his policies. More people than Bush were involved in the decision to go to war. But more to the point, the emphasis on Bush constantly undercuts Bob Kelly’s question. Imagine, for a moment, that Bush never existed. Would there still have been a rationale for war? I thought so; as I said, I thought we had one as early as 1994, and Clinton (and other Democrats) made the case for war emphatically in 1998. Until we let go of obsession with Bush, the debate just doesn’t get very far.

I put it to you that defenders of the war are essentially involved in the reverse of your proposition; they cannot disassociate their final justifications for Iraq from Saddam Hussein who they hold in their head as the epitome of evil. For example, why do you take this nonsense report about Saddam’s plot to kill Bush 1 so seriously? And even if you can 100% confirm it, I assume this justifies Cuba invading the United States, if it could? Or, indeed, any of those states the leaders of whom the United States has attempted to assassinate Pointless justification, that only makes sense because of some irrational hatred of Saddam Hussein, beyond say the Saudis, the Pakistanis, or yes your own Special Forces.

BTW the idea that George Bush should be convicted for war crimes has nothing to do with him personally; Amnesty International have supported that campaign, and I assume you have no problem citing their reports when talking about how bad Saddam Hussein was. Also note that in the UK we are equally enraged with Tony Blair, hardly the same personality as George Bush. I assume international law, nuremberg, command responsibility, political exposure, etc. mean nothing to you?

John, why do you and others always attack the writer? You have proven his point. Could you please write a coherent thought on this subject? What do US Special Forces, etc. have to do with the subject? How did you know that US Special Forces hated Saddam? This is the exact emotional reaction to this issue that Tom was expanding on.

John’s central point sseems pretty clear to me. He is responding to Tom’s charge that (many? most?) liberal critiques of the US-led invasion of Iraq are both motivated and weakened by an irrational hatred of George W. Bush. John is making the claim that, ironically, justifications for invasion and occupation of Iraq have been similarly predicated on an irrational view of a particular individual–Saddam Hussein.

I’m not sure I agree with that, but perhaps you could reply to the substance of John’s argument and give the overly-emotional-comment patrol routine (which is not only incredibly boring, but also condescending and insulting) a rest.

GC- Tom’s argument essentially attacks all critics of Bush on a personal level; they are somehow all ‘liberal’ fools who hate Bush purely for being Bush. I merely invert this for rhetorical effect, but the substance is clear; I do not see any anger that Saddam Hussein was hanged by a “kangaroo court” under U.S. auspices. Every post-hoc justification for Iraq rests on this Saddam-was-evil argument, the argument that then serves ultimately to protect Bush et al from criticism. Naturally this is not the whole story, but it is a significant part of it.

John, thank you, I misunderstood your nuances.

Exactly. And when words like “genocidal” sanctions start flying around, the conversation has already entered the realm of emotion, not logic. The “UN” did not declare their own sanctions genocidal; one former UN official did, over a decade ago. And this exactly what I mean about any kind of deeper analysis of the war getting lost in the “Washinton was as bad as Baghdad” rhetoric.

Frankly, I suggest you visit Iraq. From the perspective of Baghdadis today, the U.S. certainly looks no better than Saddam. The logic/emotion binary is nonsense; it is your argument that attempts to give the U.S. a free-pass on emotional judgements about Saddam. I elevate neither to some emotionally charged moral high-ground. The logical argument is simple: hundreds of thousands killed by the sanctions the U.S. would not let be eased (no medecine for kids, no fertiliser; it’s all ‘dual use,’ remind you of Gaza?), hundreds of thousands killed due to the U.S. invasion; this has nothing to do with Bush and everything to do with the terror he inflicted, a terror not mitigated by Saddam’s own brutality.

“Frankly, I suggest you visit Iraq….”

Yes,this entire comment puts it perfectly. What people like Nichols, GC et al try to do is hut down debate by branding their opponents illogical, or ’emotional’, while constructing emotional, illogical arguments themselves.

Even on it’s own terms it’s an unreasonable request, though. I’d be interested to see how far I would have gotten in the wake of 9/11 to demand people around here ‘stop being so emotional’ and have some perspective

John, I take those concerns very seriously, especially since I am a former member of Amnesty who quit in 1990 over Amnesty’s sanctimonious position on…well,everything, but on the Ceaucescu execution specifically. Clearly, I make moral distinctions between regimes that you do not; I believe that some are worse than others,that democracies have a positive obligation to help people oppressed by evil regimes as best they can, and I do not drench the entire question in the kind of relativistic fog — Cuba should attack us, we did it too! — that constantly excuses the need to make difficult decisions. I would add that if Tony Blair and George Bush agreed on this issue,and that they are as different as you correctly note, why not consider the possibility that they were acting on principles that were obvious to them despite their differences?

There is no relativism here. The U.S.-led-controlled sanctions on Iraq were genocidal (this is according to UN experts), and the fact that it was solely the U.S. and the U.K. who refused to remove the sanctions despite the rest of the world demanding their removal makes those states culpable for genocide. How is it relativistic to understand this point and then believe there are few differences in the moral outlooks of Washington and Baghdad? In fact, the relativist position is to claim that the former sanctions atrocity is somehow more excusable than, say, Anfal, based on the cognitive pathologies of moral distance that we all suffer from.

Difficult decisions… Really there was not one here. A state completely uninvolved in the ‘war on terror,’ with weapons inspectors roaming about their country, economically crippled… Real difficult decisions? Do something about Israel, Saudi Arabia (look at 9/11 passenger manifest…), etc. Stupid decision, not difficult.

Tom, I share the broader point that it is important to look beyond Bush for the deeper explanations for and, ultimately, assessments of the war — though I am not so comfortable with some of your categorical claims about the critiques out there. Yes, there is certainly a lot of anger out there in the political discourse. But, there is an extensive (and impressive) literature out there on the Iraq War that is more than just polemical attacks of Bush.

On the narrower point of judging (a normative assessment) the decision to go to war, I think it is logical to examine (and be critical of) Bush’s personality. This case is striking because the national security decision making system broke down so completely. Yes, others were involved in the decision to go to war insofar as they influenced Bush. But, the president made the decision without convening a single NSC meeting to weigh the pros and cons of war. There was never an NSC meeting in which Bush announced his decision. Powell found out about it somewhat matter of fact manner when Bush told him of his decision casually after an unrelated meeting at the White House in January. The problem in all of this is that Bush’s personality drove the style and process in which the decision was made. As scholars, it is important to study and understand both Bush’s leadership style and the decision-making process. We can and should do that now.

Jon, I agree that it’s well worth thinking about how Bush’s style and personality drove process, but that’s a different issue. What you suggest is reasonable and analytical. My complaint is with the people who simply assume Bush was stupid, evil, mendacious — because it’s what they assumed about him even before he was elected.

But what i am contesting is that you can make that easy distinction in the first place, as the judgements of the latter (policies) necessarily determine the judgements about the former (person).

As for the many people involved – im not sure if you are talking about people like Don Rumsfeld, Cheney, Rice, etc etc, (all of whom tend to get wrapped up with Bush) – or are you speaking about the broader currents in civil society? or maybe some yet unnamed bureaucrats and planners at mid level state and dod positions or something. if its this last one, then i ve misunderstood your point.

As for the existence of a rationale for war absent Bush – for sure, there would be an argument to be made. But who would be making it?> and in what ways? its difficult to parse out the ‘form’ versus ‘content’ of this one, and i have a hard time imagining Al Gore trotting out those tubes to the UN fully knowing the deception involved, and pushing the issue after Hans Blix and the developments in early 2003. I also find it difficult to believe that a Gore Administration would have ignored the advice of people like Shinseki and others. I don’t know this for sure, but i’ve talked pretty extensively with someone who would have had ready access to Gore’s ear on foreign policy issues, and its the clear impression i get from him.

If you are trying to contend that our discussions about the Iraq War delve too much into Bush’s Iraq War, versus some potential counterfacual war which wasnt as badly bungled but still tryin to get Saddam, that would certainly be an interesting question, but did not come through in the post that clearly, because by the end it reads too much like a defense/apologia for Bush himself, a loses focus on that ‘purer’ version of the war you may be trying to direct us towards.

You mean the same Al Gore who funneled aid to Viktor Chernomyrdin’s government, and would brook no dissent about the depth of the corruption he was enabling? Nah, not Gore. He’d never pressure the CIA to wash their intel. Except for the times he did. :)

JG, your response is very difficult to follow. Not to be rude, but what does the ACA have to do with the subject matter? As you stated though, ‘maybe i am not understanding your point’. Why don’t you re-read Tom’s post, wait forty-eight hours, then write (proof-read also, gives you added time to calibrate your thoughts) a coherent thought devoid of what I perceive as your emotions (please pardon me if I am mistaken). Not to be rude, just an advice.

Uh, its in the original post? “they choose political positions based on what they think those positions

say about themselves to others: “I support Obamacare because I love the

poor, and that makes me a good person, and certainly a better person

than you,””

Sorry, I didn’t make myself clear, I was trying to follow the logic of your argument vis a vis the central/main theme in Tom’s post and got distracted with your usage of Tom’s mention of the ACA. I will re-read your response over the weekend and provide a more detailed response.

I managed to follow his comment quite easily. Perhaps you should drop the high-handed tone, since you don’t seem to have been able to keep up.

Joe, sorry but what part of ‘not to be rude’ did you find offensive? What is going on here?

Very interesting on Iraq. But I am particularly intrigued by your comments on the island-hopping campaign against Japan. What was the alternative?

I’ve always felt MacArthur was profligate with the lives of his men in that campaign. I’m not an historian, and can’t debate the island strategy vs. the direct-into-Japan route, but MacArthur (like Patton) was emblematic of the American way of war — and I don’t mean that in a good way.

Sorry, haven’t read the whole post, but this is the 2nd time you (T. Nichols) have alluded to archival evidence that supports ‘the domino theory’. You did it once in a comment thread and you do it again here. What evidence are you talking about?

Even if the domino theory had some validity at one point, after the mass killings by the Sukarno (iirc) regime of Communists in Indonesia in ’65 (but before the U.S. escalation decisions in Vietnam), the domino theory shd have been dumped.

I suggest you read Stein Tonnessen’s paper on it at the Cold War International History Project, where it was published so long ago that I was able to use in my own book on the Cold War in 2003. Finding out, as we did, that the North Vietnamese and the Chinese were explicitly talking about “building roads to Thailand” and “smashing the US-Japan alliance” and all that stuff that wasn’t supposed to be true shed a new light on the domino theory. Whether they could have pulled out a string of revolutions is questionable; whether they wanted to is pretty clear now.

I’m not sure that it does. There’s no doubt that Marxist-Leninist (and Maoist) regimes want to expand; Soviet third-world behavior in the 1970s, after all, helped kill détente. The question is whether the theory is true: that the US had to fight for even strategically marginal countries because failure to do so would result in states ‘falling like dominoes’ until US interests were in actual jeopardy.

Dan – Hard to prove a negative, but to me, it was a major step forward for anyone (as Tonnesssen did) evrn to admit that China and other revolutionary regimes were interested in expansion. To argue that among Cold War mavens was almost instantly to get an eye roll, and what you so casually say is something about which there is “no doubt”…well, them was fightin’ words as late as the 1990s — and for some people always will be. Whether we had to oppose those expansionist aims is a different question; whether those aims existed is clear, and is a fact which a large school of historians and IR folks refused to believe for a very long time. (Corollary with Bush? Nixon-hatred. LBJ’s war, of course, but no discussion of Vietnam was complete for a long time without someone corking off about Nixon, as though Nixon’s hideous personal failings nearly single-handedly caused the war.)

If my memory is right, about 20,000 of the roughly 58,000 U.S. soldiers who were killed in the war died during Nixon’s tenure. Plus many more Vietnamese, needless to say. Also throw in the bombing and subsequent invasion of Cambodia.

Also, it’s worth recalling that just before the Nov ’68 presidential election Nixon and Kissinger deliberately sabotaged the peace negotiations that were just getting underway by telling Thieu, through various channels, to dig in his heels b/c he wd get a better deal once Nixon was in office.

Glancing just now at the account of this in David Milne’s book on Walt Rostow [full cite below]:

Oct 11 ’68: North Vietnam agrees to begin negs. in Paris if US wd halt the bombing campaign.

LBJ then plans to announce a bombing pause to begin Oct 31.

Kissinger, who had lied to Averell Harriman that he (Kissinger) was “through with Republican politics,” confers w Harriman in Paris and tells the Nixon campaign that the bombing pause is forthcoming.

Then, quoting Milne:

“Representing Richard Nixon…a prominent Chinese-American businesswoman named Anna Chennault [widow of Gen. Claire Chennault] warned the South Vietnamese ambassador Bui Diem that Pres. Johnson planned to embark upon direct, substantive negotiations. Chennault advised that Thieu should refuse to participate… since he was certain to get better terms under…Nixon than…Humphrey. This underhand ploy placed partisan politics ahead of the lives of American troops in the field. Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon share a great deal of shame for advocating a strategy that was all but treasonous…. Emboldened by the information provided by Chennault… on November 1 Thieu made a pugnacious speech in which he pilloried Johnson’s decision [to halt the bombing and negotiate] and disassociated the South Vietnamese government from Averell Harriman’s efforts in Paris.”

— David Milne, America’s Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War, pp.236-37 (emphasis added).

Yes, my mistrust of Bush played a role in the thought process that allowed me to correctly understand the situation when others did not.

No, I’m not terribly interested in reading someone who got the question so wrong explain why those of us who got it right were actually suffering from bias.

You know what you call it when your impression of a situation helps you understand and analyze the facts better, and draw better conclusions? It’s not bias, Mr. Kelly; it’s insight.

On the other hand, what we’ve seen from the right these past four years is nothing more than principled opposition.

The post has prompted a lot of discussion, which I think is useful. My own contribution is more nitpicky than anything. I think Tom sets up Andrew Bacevich as a bit of a strawman. He holds up Bacevich’s piece in Harper’s as representative of many (most?) liberal analyses of the war. I don’t think that is right. First, Bacevich’s son was killed in action in Iraq. That puts him in a different space than most analysts. I am not suggesting that his analysis is wrong or tainted(I happen to agree with much of what Bacevich writes), but in popular outlets like Harper’s his acidity is both understandable and atypical (he notes that he will remember Iraq for a different reason than Wolfowitz). Second, Bacevich is not a liberal. I don’t think he would classify himself as such, and I don’t think his writings do either. If we were to put him in a box, he is a classical realist. Third, Bacevich was writing in Harper’s, not Security Studies or IO or IS. The framing of the article befits the venue and the audience. It is in my opinion a long leap to go from that to say that his work typifies a broader problem with academic analysis of the Iraq war.

Jarrod, Bacevich was an opponent of the war and a strident critic of what he sees as US militarism long before his son was killed. It is unfair to him and his voluminous writing on this to dismiss it as the anger of a father. He was on this line of objection long before that, and I think his tone was emblematic of a major school of thought. You can say it was just a piece in Harper’s, but he’s a top scholar at a major IR program who has published multiple books on the subject.

I am not dismissing his position as that of an angry father. I am aware of his long held stance on US militarism. Only that using him as an exemplar of your argument that IR scholars cannot get perspective on Iraq because they hate Bush too much is to rest an awful lot on a individual in a unique position (He, not I, alluded to the loss of his son in the piece you link to). I’ve met Bacevich and respect him immensely, so I am probably the last person on the planet who would dismiss him in that way.

Perhaps someone has said this in the comments below (I havent read them yet), but..do you have any actual evidence for the main thrust of your post, that we can’t speak about the war because ‘liberals’ and ‘intellectuals’ have an irrational hatred of Bush? I mean a link to Gawker and an article by (the conservative) Andrew Bacevich isn’t particularly convincing

Just to follow up, the OP doesn’t actually make any sense whatsoever. There’s not even the beginnings of a coherent argument here. I’m sorry if this is rude or seen as trolling, but it really, really is nonsensical

Bacevich just blurbed Rachel Maddow’s new book on the military. If that’s “conservative,” we’re using different dictionaries.

Sure, I’ll take your word for it, but so what?

Bacevich clearly is a member of a section of the US right, one that is more isolationist and sceptical of the use of force.. perhaps they get drowned out since the US FP right got taken over by radical Leninists and idiots, but……

Anyway, and being more serious, (and once again), your post still makes no real sense.

Everything is hanging on this line:

“The real reason it’s “too soon” is that many American liberals and

American academics (not always the same group, I grant) still cannot

think rationally about the war because they still cannot let go of their

desire for revenge on George W. Bush.”

Which you provide no evidence for apart from a link to Gawker and a Michael Moore quote, (while completly ignoring the substantial, reasonable debate there has been on Iraq – look at the posts here, at Foreign policy or Foreign affairs, to name just the most obvious and mainstream publications)

Perhaps you see yourself in Michael Moore and Gawker’s peer group, otherwise I dont have a damned clue what the point of your post is

(as an addendum – yes it’s ‘too early’ to come to any firm conclusions, but so what? It’s always too early. That doesnt mean you cant form opinions as the evidence stands now)