Polls in Kenya closed 16 hours ago, but votes continue to be counted. Those familiar with Kenya and with the electoral crisis of 2007-2008 will know to distrust provisional results. In December 2007, challenger Raila Odinga seemed substantially ahead during much of the early voting, only to see that lead evaporate as returns came in from more remote districts. Despite this qualification, it does look increasingly likely that Uhuru Kenyatta will gain the presidency in the first round of voting.* In the past two weeks, there was some speculation that Kenyatta might struggle to meet new requirements for national distribution of the vote, but he’s already achieved the 25% votes bar in 32 counties. Kenyatta is currently under indictment by the International Criminal Court for his involvement in the 2008 post-election violence; if elected, he would be the first democratically elected leader to go on trial at The Hague.

Polls in Kenya closed 16 hours ago, but votes continue to be counted. Those familiar with Kenya and with the electoral crisis of 2007-2008 will know to distrust provisional results. In December 2007, challenger Raila Odinga seemed substantially ahead during much of the early voting, only to see that lead evaporate as returns came in from more remote districts. Despite this qualification, it does look increasingly likely that Uhuru Kenyatta will gain the presidency in the first round of voting.* In the past two weeks, there was some speculation that Kenyatta might struggle to meet new requirements for national distribution of the vote, but he’s already achieved the 25% votes bar in 32 counties. Kenyatta is currently under indictment by the International Criminal Court for his involvement in the 2008 post-election violence; if elected, he would be the first democratically elected leader to go on trial at The Hague.

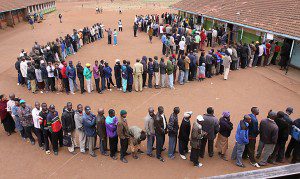

I want to make one quick note before turning off the Twitter feed and going to bed. The Kenyan Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) gambled big with technology this election. The newly created IEBC instituted biometric voter registration, electronic voter rolls, and electronic transmission of polling station results via cellular network. It is likely that the slow pace of processing BVID accounted for some of the enormous lines during the first half of the day. After numerous problems, the IEBC eventually instructed polling agents to abandon the electronic voter roll in favor of the manual roll. Nor has the count proceeded without hitches. There were nail-biting moments earlier tonight, when a server failure and insufficient hard disk space caused the electronic transmission of results to IEBC to halt for several hours.

In the days leading up to the vote, the IEBC assured voters that this electronic technology was the best safeguard against vote rigging. This placed a heavy burden on new systems of voter verification and of vote transmission to work seamlessly. Even in the best conditions, the IEBC admitted that 25% of polling stations might face cellular connectivity issues. The IEBC should also have heeded the lesson of the 2010 constitutional referendum, in which electronic vote transmission was, at best, problematic, poorly understood, and unevenly implemented. In advance of the election, it was known that education of polling agents and voters themselves was inadequate. The credibility of the election results was central to the 2007-2008 election crisis, and ensuring the credibility of results — and, equally importantly, the popular perception of that credibility — should have been the IEBC’s top priority. This was an ideal context in which to emphasize redundancy and the integrity of a physical paper trail.

So far, the IEBC has managed the voting and the count as well – if not better – than could be expected. But there exist inflated expectations about how quickly and seamlessly a new technology platform can be expected to perform. Reports continue to stream in of the failure of transmission phones and the need to ferry ballots to constituency tally centers, which may not have allowed party agents to supervise all stages of the process. Up to 8% of votes have been marked spoiled, likely due to the complexity of the ballot itself.

My worry? These failures and delays are highly unlikely to change the overall results, especially at the presidential level, and technology likely substantially improved the quality and integrity of the final results. Yet the visible problems – and the IEBC’s failure to get out in front of these problems by emphasizing redundancy – will give candidates ammunition to challenge individual races. In a worst case scenario, the losing party might raise doubts about the overall credibility of both the polls and the announced results. From there, it’s easy to imagine a route to street protests and potential violence. The first bad sign? A press conference called by the party of the trailing presidential candidate, Raila Odinga — at which the party claimed numerous election irregularities and dismissed the IEBC’s own provisional results as “figures floating on a screen.”

Stay tuned: let’s hope this is as bumpy as it gets.

* Under the new constitution, adopted in 2010, the winning candidate must win 50 percent of the popular vote and 25% of the vote in 24 of Kenya’s 47 new counties. If the candidate fails to meet that bar, which is intended to encourage cross-ethnic mobilization by parties, the two leading candidates go to a second round.

0 Comments