Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel de facto announced on Friday that the US will scrap deployment of ground-based ballistic-missile interceptors in Poland and Romania.

Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel de facto announced on Friday that the US will scrap deployment of ground-based ballistic-missile interceptors in Poland and Romania.

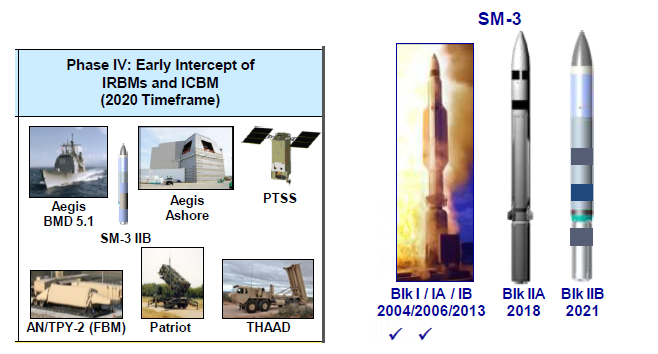

At a Pentagon press conference today, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel announced that the planned deployment of the high-speed SM-3 Block IIB interceptor to Poland (and the corresponding 4th phase of European Phased Adaptive Approach) has been cancelled. The transcript of Hagel’s prepared statement only states that the Block IIB programmed was being restructured, but the discussion in the following press conference makes it clear that the deployment plan has been cancelled:

In response to a question at the press conference, James Miller, the Undersecretary of Defense of Policy said (my transcription from C-SPAN video):

“The prior plan had four phases. The third phase involved the deployment of interceptors in Poland. And we will continue phases one through three. In the fourth phase in the previous plan we would have added some additional — an additional type of interceptors –the so called SM-3 IIB would have been added to the mix in Poland. We no longer intend to add them to the mix but will have the same number of deployed interceptors in Poland that will provide coverage for all of NATO Europe.”

In the prior plan, Block IIA interceptors would have been deployed in Poland as part of Phase III of the EPAA and then in Phase IV some or all of these would have been replaced by Block IIB interceptors. Whether the Block IIB development program is completely dead is unclear. This is a very significant development given that the Block IIB was the single greatest source of Russian objections to U.S. missile defense activities. Although there are certainly also good technical and economic reasons for cancelling the Block IIB, it will thus inevitably be portrayed as to be a major concession to Russia. Whether it will be actually be enough to satisfy the Russians remains to be seen, as many Russian statements have also objected to the unlimited deployment of the high-speed (although not as fast) Block IIA interceptor.

As was clearly the goal of the press conference, most media attention focused on the comparatively minor announcement that the number of deployed GBI interceptors in the U.S Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system covering the United States would be increased to 44 from the current 30. This involves deploying 14 additional GBI interceptors into 14 already existing silos (although in some cases, these silos need extensive refurbishing – see my post of March 28, 2012 for details) by the end of 2017. The planned number of interceptors was already at 44 when Obama took office, but his administration quickly cut this back to 30, citing a lack of a threat. Since then the possibility of restoring the number of interceptors to 44 has frequently been portrayed by the Administration as a possible hedge against future changes in the threat.

This decision will likely send conservative critics of the Obama Administration into overdrive. After all, it combines a number of popular anti-Obama narratives:

- his ‘secret plan‘ — inadvertently revealed by a live microphone during a conversation with Medvedev — to backpedal on BMD after the election;

- his general lack of appreciation of the deep existential threat posed by Russia to the United States;

- his ‘manipulation‘ of the sequester to do things that hurt Republican interests, states, and districts; and

- his fecklessness with respect to American allies.

An article in the New York Times quotes Duck-friend Sean Kay defending the decision:

Sean Kay, a professor at Ohio Wesleyan University and expert in international security issue and Russian relations, said that the so-called fourth stage of the Europe-based missile defense program “was largely conceptual” and might never have been completed.

Eliminating that portion of the program made sense, Mr. Kay said. “In effect, by sticking with a plan that was neither likely to work in the last stage but was creating significant and needless diplomatic hurdles at the same time, we gained nothing,” he said. At least some of the canceled interceptors were to have been based in Poland, which will still host less-advanced interceptors.

In the past, efforts to restructure the antimissile program provoked sharp criticism in Poland, but this time reaction from Warsaw has been more muted. Analysts have said Poland’s main goal in hosting the interceptors has been having an American military presence there as a deterrent to Russia.

I agree with Sean that there are minimal downsides to canceling Phase 4.* I am skeptical, however, that this decision will make much difference with Moscow.

The US made it very clear to the Kremlin that none of the capabilities associated with the EPAA threatened Russia’s strategic deterrent. But Moscow will likely remain worried that (1) a limited system might create problems for its nuclear doctrine and (2) the deployment of BMD capabilities will make it relatively easy for Washington to bootstrap future technologies that will threaten Russia’s deterrent. Neither of these concerns were particularly sensible before Friday, so there’s little reason to think the Putin regime will change its assessment now. Indeed, as I’ve noted before, Russian fears about US BMD are largely either symbolic or fact-free in nature.

On a final note, canceling Phase 4 of the EPAA doesn’t do very much to preclude the US from deploying more effective BMD systems in coming decades. Indeed, concerns about North Korea may themselves drive future improvements in US BMD technology. To the extent that this obviates conservative criticisms, it also explains why this development won’t likely have much impact on US-Russian relations.

*For a quick explanation of the different phases of EPAA, see Tom Colina’s piece for the Arms Control Association.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

0 Comments