OK, the 10-year retrospectives on the Iraq War are in and the debate is on. Yes, Bush, Cheney, and the neocons sold the country a bill of goods on Iraq. They are war criminals and should be held accountable. Iraq was a strategic disaster, it was a financial disaster, and for far too many it was a human and humanitarian disaster. Yes, yes, yes, the intelligence was faulty, the pundit class failed, Judith Miller was wrong, and the New York Times screwed up. The list goes on.

But, this isn’t the first time we’ve seen all of this, and it won’t be the last. Read on and be sure to take the time to watch the video clip at the end.

We’ve had several presidents and foreign policy elites exaggerate threats and discount the costs of war and lead us into tragic consequences. Truman and MacArthur told Americans not to worry about a Chinese counter invasion of Korea if we went past the 38th parallel. Johnson and most in his administration warned of global peril if we lost South East Asia. Bush and Cheney’s warnings on Saddam and WMD were only the most recent of reckless sales pitches about war. And, given how things are going with Iran, we may not be that far off on the next disaster.

This is why we need more than an understanding of what drove Bush and Cheney and how they sold this war. We need to understand why the America people bought this war – and why the American public keeps buying arguments for similar types of war.

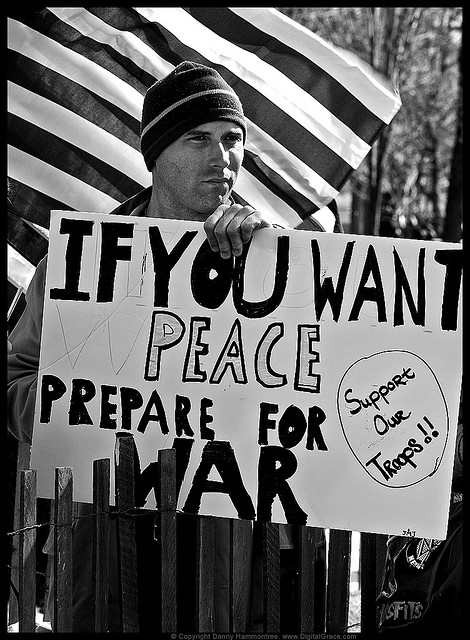

Of course there were critical voices out there. In February 2003, we witnessed an unprecedented global peace protest in more than 600 cities. For a moment, it actually looked like there might be a real and viable peace movement. The realists made their case known. Senator Robert Byrd made the strongest and most passionate case against giving the president the authority to go to war. In my little corner of the world, I made the case that there was too much excitement for war and not enough real thought about the likely costs and consequences.

But, in the end, not only did we (the war critics) not win the public debate, we got trounced. For the better part of the year before the war in Iraq, a solid majority of Americans supported the use of force to remove Saddam Hussein. By the time President Bush launched the war, roughly two-thirds of the public supported the idea. And, while public opinion does not drive presidential decisions, it does influence them – and if there is sufficient and mobilized opposition, it can constrain them. But, a decade ago, despite the efforts of some, the public was receptive to the messages coming from the administration and, in the end more Americans wanted the fight than to avoid it.

So, what drives public opinion on matters of war? It’s easy, but intellectually sloppy, to put it all on the role of elite manipulation — the “Bush lied, people died” claim. Again, I’m not dismissing the mobilization effort. But, as I argued in my 2005 book, Selling Intervention and War: The President, the Media, and the American Public, the story is more complicated. In my work, I drew heavily on John Zaller’s seminal work The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion, in which he argues that public opinion is a function of two factors: information and predispositions. As evidenced by the recent flurry of 10-year retrospectives, most of the attention tends to focus on the former and ignore the latter. The public forms opinions on the basis of information presented to it and there is a broad literature on information asymmetries, the break downs in the marketplace of ideas, the executive branch information and propaganda advantages. Clearly, a major part of the story is how the Bush administration waged a sophisticated propaganda campaign on Iraq.

But, that information is processed through a deeper set of public predispositions — or latent public opinion as I’ve called it. Arguments for war cannot be made up out of the blue. They have to have some logical grounding in a broad set of public experiences and expectations about the nature of the threat and the utility of force. Arguments must “fit” these broader predispositions in order to be effective. If we look at Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq we find a similar set of shared predispositions that conditioned the public’s embrace of war.

First, all three cases consisted of years of conditioning for war. For more than a decade, Saddam had been portrayed as a threat to the United States. He did have chemical weapons and was engaged in a nuclear weapons research program at one point; he did launch the invasion of Kuwait; he did try to assassinate George H. W. Bush; and, he was in non-compliance of the United Nations mandated inspections. The public took its cues from all of these experiences. As a result, we see pretty consistent polling throughout the 1990s on Saddam and Iraq. In 1998 – three years before 9/11 — a majority of Americans polled expressed their support for removing Saddam with ground troops if necessary. In short, the argument that Saddam posed a significant threat to the US after 9/11 was seen as both plausible and probable. Furthermore, the quick and decisive victory in the Persian Gulf War led many to accept that the Iraq War would be relatively easy.

This is similar to the public’s conditioning of the existential threat posed by communism in the decade prior to Johnson’s escalation of Vietnam in 1965. Eisenhower had coined the domino theory phrase in 1954 during the Dienbienphu crisis and the general concept festered and permeated for a full decade. By the time the Gulf of Tonkin episode, the public had already largely accepted the logics of the domino theory.

Parenthetically, today, we are seeing a similar situation unfold with Iran. For the past six years, polls suggest that the public feels that Iran more than any other country is the greatest danger to the United States. And, today, nearly six in ten say the U.S. should use military force to prevent Iranian proliferation.

Second, fear is a powerful motivator in public attitudes. In the aftermath of 9/11, Americans were anxious and scared. To be sure the Bush administration and a compliant media fueled those fears and the Bush administration actively developed strategies to fix the meaning of 9/11. But, the attacks on 9/11 were real and the American public reacted in a way that was largely consistent with other publics around the globe that have experienced direct attacks on their territory.

Third, the American public has a strong belief in the utility of military force. As Bruce Jentleson argued, however, this isn’t without limits. Nonetheless, in Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq the public believed that military power would effectively mitigate the threats to the United States. In his book How We Fight, Dominic Tierney takes the argument into areas that should make all of us somewhat uncomfortable. He argues that the American public is driven by a powerful national ideology that holds a lingering crusading ambition to over throw tyrants and to promote democracy –and when that fails, we simply abandon the effort, but usually after significant loss of blood and treasure.

This crusading ambition is more deeply engrained than we probably think. Anatol Lieven and Andrew Bacevich also add deeper historical and cultural elements into their analyses of what drives broader public support for war. This is probably why Clint Black got widespread playtime for Iraq and Roll while the Dixie Chicks were blacklisted.

Finally, there are also deeper forces that often propel humans into war. As Chris Hedges wrote, war is a force that gives us reason – it is an elixir and it is addictive. Not only for those who fight, but those societies and publics that seek vengeance or control. My good friend Tyler Boudreau commanded a U.S. Marine rifle company in Iraq and didn’t fully comprehend his own desire for war until he returned to the banality of civilian life. His book Packing Inferno: The Unmaking of a Marine is a powerful look at his personal journey of self-reflection and his request that the rest of us do the same. War is not sport. It rarely goes according to script. And, yet, too often we find ourselves returning to war by embracing the same failed arguments for it because we are “scared,” and we are “reluctant to take on ourselves” to uncover and understand our own relationship to war. So yes, let’s keep the pressure on Bush, Cheney and Rumsfeld and the rest. But, let’s at least acknowledge that there is a broader challenge out there. Here’s a clip of Boudreau presenting his main thesis — definitely worth the ten minutes of your time:

Jon Western has spent the last fifteen years teaching IR in liberal arts colleges at Mount Holyoke College and the Five Colleges in western Massachusetts. He has an eclectic range of intellectual interests but often writes on international security, U.S. foreign policy, military intervention, and human rights. He occasionally shares his thoughts about professional life in liberal arts colleges. In his spare time he coaches middle school soccer, mentors the local high school robotics team, skis, and sails.

Jon, many of the themes you touch upon are covered in Schmidt and Williams (2008) excellent article on the cultural dimensions of the debate between realists and neoconservatives (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09636410802098990 – gated version). I’m surprised it has not been mentioned in any of the Iraq retrospection pieces so far, particularly given that it is ranked as one of the top articles in the journal Security Studies.

Also, if you are at ISA next month I have a paper that deals directly with these issues. Here is the abstract:

Realism, Securitization, and Statecraft

Having lost the widening-and-deepening debates of the 1990s, realists are now

confronted with an excess of securitization, the discursive framing of political issues within the logic of existential threat. This is distressing for realism not only

because many of the issues on the ‘new security agenda’ (i.e. Food, Border, and

Environmental Security) distract states’ attention and resources away from

interstate conflict, but because as the case of the 2003 Iraq War demonstrates,

realists can be ineffective in countering security speech acts. What is it about realist political advocacy that makes it ill-equipped to desecuritize? This article turns to the relational concepts of identity and emotion to understand why political realism, at least in its modern form, is poorly equipped to mount a discursive challenge to encroaching processes of securitization. It argues that security

speech acts, particularly through their formulation of valued referents, offer

a powerful basis for collective identity which achieves a unique saliency in

the political sphere through its association with fear of existential threat. Failure to engage with these dynamics accounts for realism’s impotency when faced with securitizing moves.

Taylor & Francis has un-gated the Schmidt & Williams article.

Not entirely convinced by aspects of Schmidt & Williams piece — see my brief comment on this on R. Kelly’s post on the neocon argument. It would have been nice if the realist case vs the war had been cast in more explicitly normative terms — e.g., don’t cause more suffering than you relieve, or some such maxim — but the policy outcome would have been the same, given who was in power.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/v28/n18/tony-judt/bushs-useful-idiots

The elephant/s in the room: Israel and Zionism.

And still you can’t talk about it.