Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Tim Dunne. He is Research Director of the Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect at the University of Queensland and the past editor of the European Journal of International Relations. tl;dr warning: ~2400 words.

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Tim Dunne. He is Research Director of the Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect at the University of Queensland and the past editor of the European Journal of International Relations. tl;dr warning: ~2400 words.

In a recent lively and provocative post, Stephen Walt argues that liberal imperialists are like ‘neocons’ only more human rights-friendly. They are alike in the sense that both ‘are eager proponents for using American hard power’. And combined, these two sets of protagonists have been responsible for bad foreign policy decisions ‘to intervene in Iraq or nation-build in Afghanistan, and today’s drumbeat to do the same in Syria’.

To help cleanse the US policy community of liberal imperialist tendencies, Walt offers ’10 warning signs that you are a Liberal Imperialist’. If you fail the test, as I did, then you have the option of (1) coming out as an interventionist (2) engaging in a form of realist immersion therapy by reading texts about why interventions fail. ‘And if that doesn’t work, maybe we need some sort of 12-step program’.

The question I want to pose is whether failing the test commits you to being a liberal imperialist? Or does the particular identity construction creak and crack under scrutiny, such that it is possible to adopt a liberal position on intervention that does not ascribe to the folly and naiveté that is attributed to it?

To help address this question I’m going to offer an alternative 12-step program that critics of liberal thinking on intervention may want to enroll in. My principle reasoning is that Walt’s ‘warning signs’ lump together – and obfuscate – critical debates and distinctions within liberalism, which is why many liberals opposed the 2003 Iraq War just as they oppose a military escalation in Syria today. Some even plausibly argue that Libya came dangerously close to an illiberal intervention on the grounds that the mandate of protecting civilians morphed into the goal of regime change. Yet what no liberal countenances is ‘another Rwanda’ in which the great powers (individually and collectively) failed to take the decisive action that was being called for by the UN force commander on the ground in Kigali. Avoiding the twin problems of indifference and recklessness has been the driver of the intervention agenda that the UN has embarked upon since the turn of the new century. And this agenda has been drive forward by the search for an effective capacity to respond to mass atrocities that is anti-imperialist. I develop this point in stages 9-11 of the recovery plan.

1. There is no mention of liberalism in Walt’s essay that is not coupled to imperialism. Logically, this absence could either be down to the fact that non-imperial forms of liberal international thought are possible but have little or no traction in current US debates on intervention; or it could mean that he thinks imperialist impulses are inherent in the liberal tradition. Either way, Walt ought to concede that liberals have, for over two centuries, profoundly disagreed on both the means and the ends of so-called moral intervention.

2. It is initially necessary to separate wars of self-defense from other kinds of war. Walt does not do this; instead, wars of necessity and wars of choice are combined in his critique (Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq – with Syria going the same way if liberal imperialist win the day). Why is this move necessary? For two reasons; first, the right of self-defense pre-dates the emergence of liberalism as a comprehensive doctrine; second, almost all traditions of thinking about war and peace accept a right to use force in self-defense (pacifism being the exception). Remember here that the Afghan war was justified by a strong invocation of the individual and collective right to self-defense – one that was widely accepted as being legitimate in various capitals around the word, as it was in the UN Security Council and in NATO.

3. What generates controversy and critique are liberal justifications for going to war ‘for an idea’ when we ‘have not been ourselves attacked’, as J.S.Mill described the dilemma in his essay on non-intervention in 1859. The dominant ideas that liberals have advanced for warfare, other than self-defence, are civilization, trade/property, democracy, stabilization, and the protection of populations from genocide and other crimes against humanity. Only wars for civilization are unambiguously associated with liberal imperialism.

4. One of the few arguments that all liberals agree on, when it comes to the ‘international’, is that sovereign states possess not just rights but also duties; in this respect, the state is not a moral island that can somehow remain separate from what goes on beyond its borders. Here we arrive at a key difference between realism and liberalism. While realists can supply ‘vital interest’ reasons for intervention, they cannot coherently advance a principled argument (beyond their own personal moral integrity). This is evident in Walt’s brief discussion about when intervention is a reasonable option. He restricts his answer to (i) last resort interventions that meet the vital interest criterion, or (ii) when they can be undertaken when the likelihood of success is high. Interestingly, both examples he invokes as meeting this criteria relate to the deployment of US military forces in the wake of natural disasters such as the Haitian earthquake and Indonesia after the Asian tsunami.

Such a prudent approach has merit but begs many questions about how vital interests get to be defined (these claims were part of the rationale for the 9/11 wars) and how, precisely, can we figure out the returns on intervention in advance? Yet the biggest flaw in the realist argument is that it does not accept that other peoples have the same basic right to security from arbitrary violence.

Rather than starting out on the basis of the fact that genocide and other crimes against humanity are morally wrong and we have some responsibility for preventing them from occurring – or responding effectively when prevention fails – realists prefer to deny any obligation to protect peoples in mortal danger (especially when they live in ‘faraway lands’, as warning sign #3 puts it). Liberals, on the other hand, begin with the recognition that being serious about human rights means accepting a duty to protect – even if, in the last instance, it may be that the policy options for ‘doing something’ are limited for fear of making a bad situation worse. The difference here is that, for liberals, a prudence-led decision not intervene can only be a policy choice of last resort – it cannot be the opening premise.

5. No-one today self-identifies with liberal imperialism. This was not always the case. As several authors show in my forthcoming volume (co-edited with Trine Flockhart), Liberal World Orders, nineteenth-century liberals advocated imperial rule in order to civilize ‘backward’ peoples (with the further embedding of European domination being a welcome side-effect). It was taken for granted by Mill and many other thinkers of the long nineteenth century that international society was divided into a civilized sphere in which the law of nations applied, and an outer zone where it had no place governing statecraft. Probably the clearest advocate of a dual system of order in which sovereign rights of independence and self-determination applied only between civilized countries.

Today liberal imperialism, as an ideological justification of rule by one polity over another, has been thoroughly deligitimated by the end of empire; so thoroughly discarded that it is now unthinkable for a political leader to stand before the UN General Assembly and call for the return of colonial rule – to do so would be to invite ridicule and isolation. Even the term ‘trusteeship’ has been deleted from the dictionary of diplomacy since it carried too much baggage from the League of Nations era when imperial polities used the idea to prop up their waning empires.

6. While discredited as a term, certain forms of argument associated with liberal imperialism were forcefully advanced in the early part of the last decade. In this respect, Walt is right to note that in the contemporary era neocons and some liberal internationalists advocated a return to ‘empire’ and imperial modes of ordering the world. Yet such claims were largely greeted with derision by those outside a narrow but influential band of Anglosphere ideologues: in the context of this ‘neocon moment’ in which empire made a comeback, realists kept their head while the intellectuals associated with the George W. Bush administration appeared to lose theirs.

7. A more common affiliation on the part of those interested in the politics of liberal interventions is internationalism rather than imperialism. These two modalities of ordering have often co-existed – indeed, the struggle between these two conceptions of international order better capture early IR than ‘realism vs idealism.’

Liberal internationalism was a doctrine that viewed the international as being modifiable through the gradual incorporation of values (justice) and institutions (law) that had made great headway in domestic liberal polities. Central to liberal internationalists today is a belief in conditional sovereignty. The American international lawyer James Bryce put this nicely, in the early twentieth century, when he argued that the ‘absolute sovereignty for each is absolute anarchy for all’.

8. Contemporary debates inside the UN about intervention draw from the tradition of liberal internationalism. A sovereign’s legitimacy derives from an acceptance of a responsibility to protect their peoples by ensuring their basic right to security from systematic violence. Should a state fail to exercise its responsibility to protect (or R2P) then this obligation is transmitted to the international community who must either assist the government in ending the atrocity, or intervene against their will if they are the cause of the crisis. If we take the distribution of responsibilities for ending mass atrocities seriously, there is not an option to ‘sit this one out’ (presumed in Walt’s warning sign #2) in either a moral or a diplomatic sense. When it comes to genocide, sitting it out has been the regular case in US foreign policy – not the exception.

While R2P is regularly invoked by UN institutions, liberal states, and human rights NGOs, the extent to which it has guided the foreign policies of great powers is underdetermined. What is undeniable about the diplomacy of responsibility over the last decade or so is (i) there is now much greater clarity about how responsibilities for ‘doing something’ about atrocities are distributed in the international community (ii) the normative status of atrocity prevention/response is sufficiently developed such that the UN Security Council has modified its mission to maintain international peace and security in a way that incorporates protecting populations at risk (iii) partly as a result of the previous two points, it has become increasingly difficult for world leaders to ‘pass by on the other side of the road’ when an atrocity crime is occurring.

9. The absence of self-identification to the category of liberal imperialism does not mean the category is devoid of meaning from an analytical point of view. At what point, then, does liberal internationalism shade into imperialism? I would argue that liberalism becomes imperialist under the following conditions: first, when the goal of the intervention is a particular kind of regime change in which it is envisaged that liberal democratic institutions will be built after the old order has been swept away. Second, liberal imperialists are prepared to abrogate to their own state a ‘right’ of humanitarian intervention: internationalists, on the other hand, believe that intervention is a duty that must be sanctioned by the UN Security Council. Third, internationalists intervene (as a last resort) to save strangers not to civilize them (as previous imperialists believed).

10. Even when an R2P situation has met the ad bellum criteria (just cause, last resort, right intent, legitimate authority), this does not mean force should be used unless it can be shown that its application is likely to bring about the desired outcome. This prudential element is referred to by Gareth Evans as a calculus about ‘the balance of consequences’. Therefore, in contrast to warning sign #6, cool-headed military strategy will be of paramount importance in determining whether and how intervention proceeds. It is worth noting here that virtually no reputable advocate of R2P has been mobilizing for armed intervention in Syria on these grounds – even if they regret the failure of the Security Council to speak with a single concerted voice and their concomitant inability to impose stricter non-military sanctions on the Assad government.

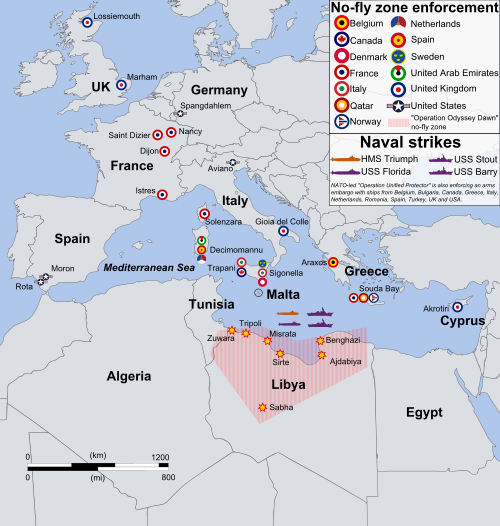

11. Properly implemented, R2P is not informed by imperialist values or practices. Yet, in an imperfect world, we know that moral justifications for the use of force are often muddled. The 2011 war to protect civilians at risk from Libyan armed forces is a case in point. Within a few short weeks after Operation Odyssey Dawn began, Sarkozy, Cameron, Obama and co-signed an editorial in which they presented an outcome short of regime change as a ‘betrayal’ of the Libya people. Instead of confusing the normative justification for war, they should have stuck to the script of Security Council Resolution 1973. Some time previously, Bismarck well understood the importance of moral consistency when it comes to war: ‘woe to the statesman whose arguments for entering a war are not as convincing at its end as they were at the beginning’. This blurring of the mandate caused considerable difficulties for the legitimacy of the action, as R2P came to be represented by some intellectuals (and by President Putin) as being an imperialist doctrine rather than a model example of the Security Council taking timely and decisive action.

12. While much of what has been discussed above rests on the claim that liberal ordering does not have to be imperial in its form, there is a sense in which the historic tension between imperialism and internationalism is part of the history of the present. The agenda of producing freedom, installing democracy, and protecting rights – all entail policies that seek to control peoples, set conditions, and justify the application of coercive instruments. Being mindful of how internationalism and imperialism can become blurred in practice is a necessary corrective to the hubris that accompanies internationalism.

***

Early in the post Walt offers liberal imperialists the advice that Stanley Hoffmann (one of the most eminent liberal thinkers in the history of IR) once offered to would-be interveners: ‘The road to hell is paved with good intentions’. This remains a salutary warning. But the road to hell is also paved with the tombstones of countless victims who were slaughtered because genocidal murderers were shielded by a presumption against intervention. Fashioning a politics of protection against the words crimes against humanity is a challenge that demands intellectual and institutional courage. It also demands – and here is where realists play an important role – that consideration be given to the perils of intervention and the limits force as a protector of the last resort.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

What is simply missing from this piece is any non-North American/European perspective. Interventions of any kind will have no moral purpose while the U.S. (with its prison system, death penalty, guantanamo bays, black sites, drone killings, illegal wars, etc.), Israel (with its open racism, war crimes on Gaza, crushing of the human spirit and bones in the West Bank, and bellicosity with Iran), the U.K. (see U.S.A), and so on, are equally at risk from intervention. There is a simple point here that no ‘liberal’ understands; for much of the world what goes on in Syria, Libya or elsewhere may be barbaric and is viewed indeed as something that should be stopped, but above all this it is the United States and its allies that should be stopped first; both for their repeated unapologetic war crimes, and their version of neoliberal globalization, whose body count is just as high. Until these problems are solved, arguments like this will fall on deaf ears outside the echo chamber.

Haven’t had a chance to read this yet, but the link in the first sentence needs fixing: it’s supposed to go to Walt’s post but it actually goes to a Doyle piece.

Thanks. Should be fixed now.

Thanks. Should be fixed now.

Man, it’s a sad day when I find Walt more compelling than Dunne :-/ One of the crucial points is that liberals, consciously or not, only seem to intervene where it is convenient (I think Walt mentions Bahrain) thus rendering the whole premise of projects like R2P bankrupt. R2p is an imperialist cover and it is a “model example of security council action”, it’s both and it has to recognize its genealogical heritage or suffer repeating the same mistakes.