Note: this post was co-written with PTJ. Apologies for the comparative lack of structure and the fact that it is a bit repetitive. Note also that it contains a link to a temporarily un-gated copy of Jackson and Nexon (1999). Thanks, SAGE!

In yesterday morning’s post, Phil writes:

One manifestation of this misunderstanding is that “rational choice” or “choice-theoretic” work is often said to favor the agency side of the structure-versus-agency debate. See, for example, this recent post by Dan Nexon, or the paper it’s based on. I don’t mean to single my Duck colleagues out, though — the notion that rational choice theorists aren’t particularly interested in structure is quite common.

But I never wrote that “rational choice [sic] theorists aren’t particularly interested in structure.” Rather, we wrote that “choice-theoretic approaches tend to treat actors as autonomous from their environments at the moment of interaction, not so experience-near and social-relational alternatives [emphasis added].” This is a very different claim.

How so? We agree, albeit in a qualified sense, with Phil that:

Most discussion of the observable implications of game-theoretic models focuses primarily on how equilibrium behavior changes in response to changes in structural conditions. In fact, if one were to insist on committing the error of arguing that a language prevents its speakers from discussing that which they just so happen to rarely discuss, it would probably be more accurate to say that “rational choice theorists” put all their emphasis on structure and trivialize the role of agency.

The following comments focus on applied choice-theoretic frameworks. In principle, such accounts are agnostic about critical inputs; preferences and other dispositions can come from anywhere. In practice, however, this is not the case. For example, expected-utility accounts in political science tend toward locating the source of dispositions in social and cultural structures. One prominent reason is that political scientists usually prefer not to infer preferences from behavior. And it is much easier to specify a set of preferences ex ante if one derives them from, say, an actor’s location in a system of economic exchange or electoral competition.

Indeed, we are pretty explicit about this in the paper. We have a short section entitled “Moving Beyond the ‘Rationalist-Constructivist’ Debate” in which we note that:

Some scholars posit the ‘rationalist-constructivist debate’ as marking a fundamental division in the field. Much of the substantive logic behind this dichotomy involves combining disagreements over thick contextualism and actor embeddedness into a single continuum, in which rationalism denotes a commitment to both thin contextualism and actor autonomy (Price and Reus-Smit, 1998). We agree that such a framing served important disciplinary purposes over a decade ago, but it now suffers from significant problems…. [T]he opposition of rationalism to constructivism follows only from a very narrow reading of rationalism: as a claim that the decision-making procedures that drive human choices are both invariant and also structured by unmediated and objective features of the world.

To circle back to the key distinction: our claim about “actor autonomy” in modal choice-theoretic frameworks is not a claim about the sources of preferences or even decision-making logics, but rather about the model of social action deployed in applied theories. At the moment of action — which is, in this work, the moment of decision — the mechanism at work is lodged inside an autonomous agent. To butcher an old philosophical problem, we might just as well be discussing a brain in a vat.

But this whole line of argument is probably blurring PTJ’s and my attempt to distinguish between philosophical and scientific ontology. In a sense, we’re at risk of arguing about the former rather than the latter. Again, the issue is practical application of choice-theoretic frameworks. Here’s what we say in the paper:

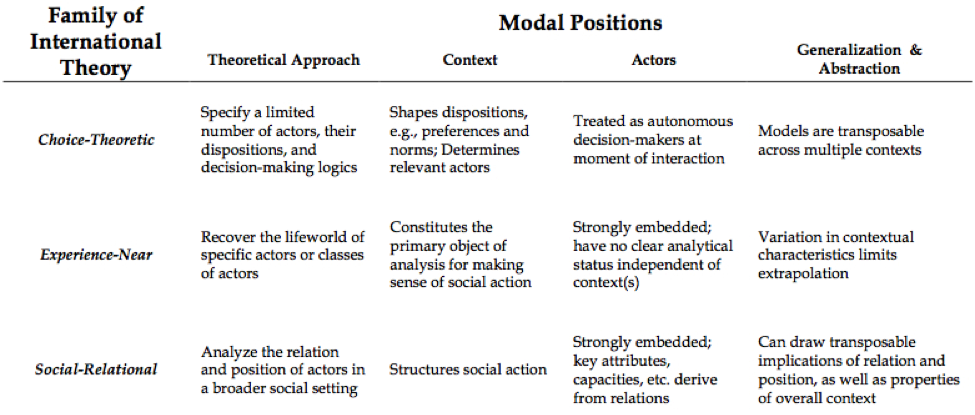

Choice-theoretic approaches include a variety of different theories that explain outcomes by specifying a limited number of actors, their dispositions, and their decision-making logics. Social, cultural, and material contexts supply dispositions and may even explain variation in decision-making logics, but theories themselves treat actors as autonomous decision-makers. Examples include expected-utility theory, many psychological approaches to international politics, and standard implementations of “logics of appropriateness.”

And here’s the table, which should further clarify what we mean and what’s at stake:

What we describe as choice-theoretic accounts catches up what Charles Tilly called “standard stories” (PDF) while recognizing precisely that structural contexts do a fair amount of work in the underlying theoretical apparatus of these accounts. This is, we think, a feature rather than a bug of our framework: it attempts to sidestep the debate Phil’s engaged with and focus our attention on the ‘paradigms’ associated with explanatory theories… their scientific ontologies.

In a number of rational-choice approaches, the paradigm of social action is what Dewey and Bentley call “self-action” — see Jackson and Nexon, “Relations Before States: Substance, Process, and the Study of World Politics,” European Journal of International Relations, 1999 (temporarily un-gated PDF). This means that the actors are conceptualized as standing independent of one another in a fundamental way, and the source of action comes from within the actors: from their desires, their preferences, their internal dispositions.

The problem, as Talcott Parsons pointed out about 80 years ago, is that one can’t theorize social action understood in this way, so in practice what utilitarians and other decision-theoretical scholars do is to talk a lot about the strategic situations within which these actors find themselves, and reason from situations to outcomes. At most, this shifts applied decision theory into the realm of what Dewey and Bentley call “inter-action,” but remains outside of their third category: “transaction,” in which social action arises not from the doing of autonomous doers, but the configurations of social process out of which actors arise in the first place and keep on arising as their borders and boundaries are (re)inscribed in practice. The point is that decision-theoretic accounts require actors to be constitutively separate decision-makers at the moment of action, regardless of whether their preferences come from purely “domestic” considerations inside of themselves, or from the strategic-interactive environment within which they find themselves.

Consider Erik’s comment on the post in question:

why do you consider actors autonomous from their environment a the moment of decision in choice-theoretic approaches? One popular interpretation presently pursued is that the individual is ‘partly’ free from environmental influences, only in the sense that some part of the explanation for an action needs to refer to the individual and that individuals’ decision. Lars Udehn made this distinction in 2002 in Ann Rev Soc. The latter sense of explanation is quite weak, and does not posit individualism in the sense you propose. After all, the individual is not free to choose their (a) interests, (b) available strategies, (c) who they are interacting with, and in fact do not ‘choose’ their decision because that is provided by the structure of the interaction in combination with the psychological factors, etc. that are relevant to the decision. The interpretation you appear to favor, I suspect, may not be the ‘modal’ interpretation in political science or economic theory more generally.

This line of argument confuses the proximate causal source of individual preferences with the model of social action specified in that framework. And it is in the model of social action that the “actor autonomy” we are concerned with actually lies. Strategically interdependent preferences of individual actors are not the same thing as a collection of relationally embedded actors. Hence, our trichotomous distinction.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Thanks. This clears things up. The distinction between “self-action”, “inter-action”, and “transaction” is really helpful. I mistakenly thought you were arguing that “choice-theoretic” work necessarily falls into the first category, and ended up arguing that much of it belongs to the second without realizing that your real point concerned the third.

Bumper-sticker version: both logics of appropriateness and consequences *focus* on actors as brains-in-vats, but lack a theory of agency, and so ironically end up being structural theories.

The question I asked was whether we are in fact talking about different models for explaining social action. I would rephrase the question a little bit. Are internal beliefs and preferences useful in describing social action, even in relational accounts? That is, at some point, when engaging in explanations for some social action, is it useful to think of individuals pursuing rational strategies as a crucial step in explaining an outcome?

Turning it around, is it possible to explain social action without any reference to beliefs, preferences, or interests? And, would those explanations seem compelling?

I think that the answer to this question is almost certainly no.

The more important question is whether the whole of social action can be

understood through this framework. This was Parsons’ target (although he adopts neither an experience-near nor relational approach to solve the problem), and I tend to agree with those who discount this approach. To react to it by claiming that choice has no role, however, seems to me to be largely unsustainable.

‘Turning it around, is it possible to explain social action without any reference to beliefs, preferences, or interests?’

Yes. Bourdieu, for example, does not use an intentional theory of mind. A habitus does not instantiate beliefs, desires, or interests. Though you might want to define action as ‘behaviour with intent’, in which case the answer is indeed ‘certainly no’, but trivially.

I can also imagine structural-functionalist explanations not relying upon intentional states to explain social phenomena, because they explain with with reference to systems that constitute and stablise society. While some such systems may involve strategic interaction, this is not determined. At least, this is how I understand S-F.

Foucaultians do not explain with reference to mental states.

It seems to me that there are many methodological traditions in which it is both possible and common to explain without talking about beliefs and desires. Perhaps you do not find those explanations compelling, but I bet you that if I pressed you to say why, your argument would beg the question.

The question I am asking is whether any IR folks have a theory of social action—highlighting the social action part, and not society or something else—that can completely

abandon methodological individualism. By this, I mean that some part of the explanation of social action does not cite the interests, beliefs, capabilities, etc. of individuals. The authors you talk about, you’re right, emphasize different elements of social structure; however, the crucial point is whether they would not invoke any of these elements in explaining action.

Take Bourdieu. He may not have a theory of mind; neither do many rationalists. But the habitus certainly conditions internal mental operations that help explain individual action. That may not be all that it does, but its an important element.

On S-F, the case is much clearer. Structural functionalists, building on Parsons’ work, certainly took

the notion that social action is goal-oriented very seriously. Parsons key argument in SSA was that goals cannot vary randomly because then predictability

in society is impossible; this assumes the rationalist setup is basically right that there is goal-oriented action.

In sum, I am still not persuaded that one can claim that in explaining social action–emphasizing the social action part–that one can entirely discount methodological individualism; there needs to be hybrids instead of positing separate ontologies.

Rationalists definitely have a theory of mind. There are a few terms for it. ‘Folk psychology’ is one. It is that actors have beliefs and desires, and their preferences or actions are based on an attempt to realise their desires based on their beliefs. Beliefs and desires are intentional, in that they involve the mental representation of possible worlds.

Bourdieu is not a methodological individualist, as his theories locate action in an interplay of structure and agent, albeit differently from, say, the critical realist understanding in which actors may be intentional. But the important point here is that Bourdieu’s theory of mind does not explain action by reference to beliefs, preferences, and interests. As you have claimed that no compelling explanation can be offered without reference to these things, I think Bourdieu is a good counter-example.

Post-structuralist work in IR frequently makes no references to the mental states of individuals.

The suggestions that we must avoid ‘discouting’ methodological individualism and that we should build ‘hybrid’ ontologies confuses me. Either something is methodologically individualist or it isn’t. If your ontology has room for individual actors capable of intentional representations, then maybe you’re an MI or maybe you’re not. Methodological individualism isn’t a variable; it’s a basic assumption as to what action is and how it must be explained. Nor can ontologies be easily hybridised. They’re build upon axiomatic assumptions or wagers as to what social reality is and how we experience it. If you find post-structuralist explanations to be unhelpful because they lack agency, you can’t simply add some agents to them. This is why explaining the interaction of structure and agency, for example, has been so difficult and has received so much philosophical attention.

Erik Ringmar, “On the Ontological Status of the State,” here (https://www.academia.edu/1328351/On_the_ontological_status_of_the_state). Also, more self-promote-y: Krebs and Jackson, “Twisting Arms and Twisting Tongues,” here (https://www.polisci.umn.edu/~ronkrebs/Krebs%20&%20Jackson,%20EJIR%202007.pdf).

Be careful not to confuse the fundamental ontological claim “actors don’t have state of mind” with the scientific-ontological claim “we don’t need to use ‘state of mind’ as a term in our accounts.” As far as I am concerned it is not all “certain” that Bourdieu or any other relational thinker (my tastes run more to Tilly and Foucault, but that’s another post altogether) needs “internal mental operations” to explain anything. And I certainly don’t think that anything that I have ever written “certainly” needs such things.

I also think you conflate things by lumping together “interests, beliefs, capabilities, etc.”as though they were all of a piece. Capabilities can be defined in pretty purely relational terms, and don’t require anything like a theory of mind or mental states. Beliefs, not so much. Interests, well, that all depends on whether we’re talking about actual interests of actual actors, or abstract interests posited in a model, doesn’t it?