I sometimes surprise people when I say that I have no idea what rational choice is.1 How can a game theorist say such a thing? Especially one who spends so much time on the internet arguing about rational choice?

Well, of course I have some idea what it is. The point is that there is no coherent body of work which possesses the properties so frequently attributed to “rational choice.”

Approximately 99% of all statements I’ve seen made about rational choice are demonstrably false. About half assert that rational choice leaves no room for things I’ve seen incorporated into equilibrium-based game-theoretic models.2 The rest assert that rational choice assumes things that many extant models do indeed assume, but which needn’t be assumed. If I were to observe that [X] figures prominently in continental European scholarship but receives little to no attention in the Anglosphere, I would be a fool to declare that the English language inherently precludes discussion of [X]. Yet that is almost always what people are doing when they say that “rational choice” assumes this, that, or the other thing.

In order to construct a formal model in which actors maximize (expected) utility, the only thing that absolutely must be assumed is that people Have Preferences that Won’t Cycle. I call this the HPWC criterion.

That’s it.

Really.

One mistake people make is to assume that such models require us to assume that people are “rational” in the ordinary language sense of the word, which roughly corresponds to assuming that human behavior resembles that of Homo Economicus.3 This is understandable — if I could go back and time and tell every game-theorist who ever put word to page that use of the R-word would result in receiving repeated roundhouse-kicks to the ribcage, I would — but it is nonetheless mistaken. Yes, lots of game-theoretic models do assume that human behavior resembles that of Homo Economicus, but again, it’s just as nonsensical to say that “rational choice” requires such an assumption as it is to say that a concept rarely discussed by scholars in the Anglosphere is one that the English language is not equipped to handle.

Without anyone noticing, apparently, many scholars have analyzed game-theoretic models in which people have trouble controlling their own behavior (ex1, ex2, ex3), hold other-regarding preferences(ex1, ex2, ex3), or fail to collect information they know to be both available and pertinent (ex1, ex2, ex3).4 There are even formal models of identity choice (ex1, ex2, ex3).

That brings me to the other common mistake. Many people believe that such models view human behavior as the outcome of careful, deliberate, conscious choice. But the “choice” part of “rational choice” is every bit as misunderstood as the “rational” bit. What these models necessarily assume is that actions expected to bring about outcomes of greater value are chosen over outcomes that bring about less value. Strictly speaking, most models assume that actors always choose the strategy that maximizes their expected utility, but some models merely assume that such strategies are more likely to be chosen. And most scholars who seek to evaluate the observable implications of equilibrium-based game-theoretic models do so by determining whether outcomes are more likely to occur under conditions where the strategies that would produce it are more likely to maximize expected utility. Game theorists tend to be relatively uninterested in whether people are more likely to choose A over B when A yields greater expected utility because they sat down and thought carefully about it as opposed to employing reliable heuristics or whatever.

One manifestation of this misunderstanding is that “rational choice” or “choice-theoretic” work is often said to favor the agency side of the structure-versus-agency debate. See, for example, this recent post by Dan Nexon, or the paper it’s based on. I don’t mean to single my Duck colleagues out, though — the notion that rational choice theorists aren’t particularly interested in structure is quite common. This is both sad and ironic, given that most discussion of the observable implications of game-theoretic models focuses primarily on how equilibrium behavior changes in response to changes in structural conditions. In fact, if one were to insist on committing the error of arguing that a language prevents its speakers from discussing that which they just so happen to rarely discuss, it would probably be more accurate to say that “rational choice theorists” put all their emphasis on structure and trivialize the role of agency. I’ve not only heard people express this very criticism, but I know at least one game theorist who says that studying game theory has made him skeptical of the existence of free will. If someone could explain to me how “rational choice” can simultaneously be guilty overemphasizing agency and yet also trivializing it, that would be great.

Consider the following example. Quinn is in a long-distance relationship. S/he has plans to go see his/her significant other this weekend. However, weather reports are looking grim. Moreover, Quinn and his/her partner have been arguing a lot lately. Let’s write down a simple decision-theoretic model. Quinn goes on the trip if and only if EU(go) > u(stay), with EU(go) = pt + (1-p)(a – c) and u(stay) = a, where p is the probability that Quinn arrives at his/her destination, t is the payoff from the couple being together, a is the payoff Quinn receives from spending the weekend alone, and c is the cost of getting stuck in an airport for the weekend or getting in an accident on the road or whatever other tragedy might be wrought by inclement weather. Our very, very simple model tells us that Quinn will cancel his/her trip if p is sufficiently large (specifically, if p is greater than c/(t – a + c), for those playing along at home). It also tells us that Quinn would cancel if t was sufficiently low (specifically, if t was less than c((1/p) – 1) + a). In other words, the models allows either structure or agency to bring Quinn to cancel. The model itself does not give us any reason to consider one factor to be more important than the other in any universal sense, though a decision to cancel at certain values of p and c might well leave Quinn’s partner feeling pretty concerned about the state of their relationship.

Too straightforward? Let’s consider another example.

Dan said in his post that “Choice-theoretic approaches tend to treat actors as autonomous from their environments at the moment of interaction, not so experience-near and social-relational alternatives”, where such autonomy implies “that actors are analytically distinguishable from the practices and relations that constitute them.”

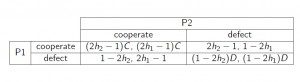

Consider the following 2×2 game.

Let hi refer to i‘s history of cooperation, with values closer to 1 indicating that i has generally cooperated and values closer to 0 indicating that i has rarely done so. Let C be some constant greater than 1, reflecting the returns to mutual cooperation, and let D be a constant less than 1, reflecting the tragedy of mutual defection.

Note that the structure of the payoffs implies that the players derive value from cooperating with those who have cooperated with them in the past while deriving value from defecting against those who have defected against them in the past. In fact, it is straightforward to show that mutual cooperation is sustainable in equilibrium if and only if h1 ≥ 0.5 and h2 ≥ 0.5.

In other words, what we have here is a game-theoretic model in which utility-maximizing behavior not only depends on past patterns of interaction (as it does in many iterated games), but where the value of cooperating or defecting is intrinsically relational. Now, it’s not at all clear to me that this model tells us anything particularly insightful. If I was really trying to advance our understanding of how social relations affect patterns of international cooperation, I’d want a more complicated model. But that wasn’t the point. I was only trying to demonstrate that it’s entirely possible to construct game-theoretic models that do not make the assumptions Dan and PTJ associate with “choice-theoretic” work.5

To sum up, the assumption that people maximize (expected) utility is much weaker than many people realize. Again, so long as people have preferences, and those preferences don’t cycle, we’re in business. To be sure, there are situations where even these assumptions don’t apply. Sometimes people don’t know what they want, and we all hate going out to dinner with these people. But that’s not what most people have in mind when they talk about the limitations of “rational choice”.

Mostly, they’re telling people to avoid learning a language because most of the people who speak it don’t talk about the right types of thing

UPDATE: I should have explained what it means for preferences to cycle. The idea is this: if I prefer A to B and B to C, but prefer C to A, then my preferences cycle. Forced to make a decision between any two of these three options, I can, but there’s no meaningful sense in which I hold a preference overall because if all three options are put on the table, I can’t pick a favorite. If I preferred A to B and B to C and A to C, on the other hand, then I’d have coherent preferences and there’d be no problem.

There are other points I should have addressed in the post that have come up in the comments. I encourage you to read them.

1. Following convention, I use the term “rational choice” here to refer to the body of work sometimes also known as “rational choice theory”, not to the act of making choices which are rational.

2. Judging by the way people use the term, it seems clear that not all “rational choice” work is game-theoretic, but any work containing a formal model in which one or more actors maximize (expected) utility is “rational choice” more or less by definition.

3. See this previous post for a discussion of that assumption.

4. Notice that most of the examples I linked to were published in economics, where one might think the slavish commitment to Homo Economicus would be strongest.

5. Note that the quote I pulled out of Dan’s only offers a claim about what “choice-theoretic” work “tends to” do. However, I have frequently encountered stronger versions of this claim and so thought it worth providing an example of what a counterexample might look like.

6. When I say “mostly”, I mean “mostly.” I understand that many claims made about “rational choice” are not intended in this light. But I do think it’s safe to say that most are.

I am an assistant professor of political science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. I mostly write here about "rational choice" and IR theory. I also maintain my own blog, fparena.blogspot.com.

This is an interesting post in a long series of contributions that you have made to Duck. I just want to pose a few questions:

1. Is the problem of not enough and giving too much agency really the problem of collapsing the term agency (when perhaps we mean praxis) and ontology with the language used to describe rational choice theory?

2. Is the only way to reject free will to be a structural determinist?

3. Are you saying that all rational choice is pluralistic and only adheres to your HPWC criteria, or that rational choice theories possess a certain family resemblance that coheres it together under a single label?

4. Do you think that thick and thin rationality are useful dichotomies within rational choice theory?

5. The only example of structure produce in RC lit, that I can think of, is the latter part of “The Evolution of Cooperation” where Axelrod talks about communities produced by decisions. Are there other examples of structures being utilized by RC theorists?

Glad you enjoyed the post, Matt. Great questions.

1. I’m not entirely sure what you’re asking here. Could you clarify?

2. Certainly not. I apologize if I gave the impression that I thought so. My point is simply that the study of game theory pushes some people in the direction of structural determinism. That’s not something you’d expect from a body of work that allegedly pays little attention to structure.

3. I didn’t meant to suggest that all of “rational choice” is pluralistic. There are (many) people who clearly count as rational choice theorists — however we define that term — who have a very narrow view of what type of work is valuable and what types of substantive assumptions are worth making. My point is only that it is possible to incorporate most any set of substantive assumptions about what actors know and want — and who the important actors in IR are — within game-theoretic models. So long as you don’t violate HPWC, that is. Thus, so long as “rational choice” is used to refer to any work in which actors are assumed to maximize (expected) utility, as it currently is, the vast majority of claims about what “rational choice” leaves no room for are simply not true. Put differently — it may well be true that a fairly limited range of ideas ever get incorporated into game-theoretic models (though I think there is *somewhat* less truth to this than many people realize), that still doesn’t justify claims about what *can* be done with the method. Yet, sadly, there are many such claims out there.

4. Yes, that’s a useful distinction. McCarty and Meirowitz’s Political Game Theory references that distinction, in fact, arguing that all that’s necessary to construct game-theoretic models is thin rationality. I probably should have used those terms above.

5. I suppose it depends on what one means by “structure”. If we use this term to refer to any factor outside the control of the actors whose decisions are being analyzed, then a very large body of work does. After Arrow’s paradox and McKelvey’s Chaos Theorem, a lot of “rational choice” work in American and comparative politics focused on “structure-induced equilibrium” and how the specific rules of specific political institutions ensure certain outcomes — outcomes that would be different if the same actors, holding the same preferences, were to enact legislation under different institutional rules. The influence of this work can be found in some IPE work, where authors analyze models whose results really only apply to institutions with the particular rules of the UN or IMF or what have you. There’s work on conflict management that analyzes the implications of managing conflict in different fora on the likelihood and distributive character of agreements. I would say that Bdm et al’s selectorate theory is a very structural theory — almost all of the heavy lifting is done by the nature of (relatively unchanging) domestic political institutional arrangements. Finally, I’m working on a paper that analyzes the likelihood of conflict between minor powers as a function of the distribution of capabilities among major powers — or the impact of “structure” in a Waltzian sense on the behavior of the rest of the system.

To clarify #1, my point was to respond to your claim that critiques of RC argue against the lack or the overabundance of agency, thus occupying two contradictory positions. What, I think, these critiques get at is not the quality or quantity of agency, but the way ontology gets described. Whether talking about rules in institutions that structure equilibriums, interdependence of logic in decision making, the social learning involved, or a combination of all three gets criticized for not making the ontology complicated enough. The actors are reduced and idealized too much for useful explanation (of course, this may amount to an argument between scientific ontologies and thus be difficult to translate between the two positions). On the other hand, RC might criticized for not investing enough intellectual resources into explaining large social structural changes (or the ability of agents to initiate that change), what I will call praxis. This inability might stem from not fully explaining restraints on agents, not examining the unstable faults of the social structure that might necessitate change, not looking at the structural position of the agents, or not qualifying the micro to macro relationships that explain how small changes possess larger structural effects. One can have different combinations of this critique based on agents (ontology) and agency (praxis). It’s easy for people to slip between agent and agency to simply using agency to mean both praxis and ontology. In the practical, but not logical, use of language, one can have too much and not enough agency.

Thanks for clarifying. I see what you mean now.

I don’t agree that the type of work we’re discussing reduces/idealizes actors too much for useful explanation in a universal sense, but I’d admit that it’s not particularly useful for certain purposes — some of which you identify. Fair points.

That said, I still think that *some* of the reason RC gets criticized both for putting too much emphasis and too little on agency is that no one really knows what the hell RC is. The term refers to several distinct, albeit related, negative stereotypes as much it does any cohesive body of work.

Are you sure: “Sometimes people don’t know what they want, and we all hate going out to dinner with these people. But that’s not what most people have in mind when they talk about the limitations of “rational choice”.”

That this is the case? That’s certainly what I have in mind when I critique rational choice; people often don’t have preferences, if they do they often change without observable reasons, preferences are not commensurable between different people (i.e. who is the rational man you are theorizing? Are the preferences you discern for him the same as the man sitting next to him; how would you know (beyond banalities; not wanting to die etc.)? I like to go out to dinner but some days- even with people I really like- nothing will make me do so… Are the preferences of Obama the same as Netanyahu? Etc., etc., etc.

The criticisms of “rational choice” that I have heard/seen most frequently concern a) the assumption that people know everything, b) the assumption that people are narrowly self-interested, and c) the assumption that people choose the behaviors that will allow them to achieve their goals. These are all things that many people think “rational choice theory” assumes, for whatever reason. Another common critique is that the thin rationality that game theory actually requires, what I call HPWC, is non-falsifiable. (Which it is, but if it was impermissible to make non-falsifiable assumptions, we’d all be in serious trouble.) These critiques do not concern the existence of preferences. So, yeah, I’m fairly confident that it is correct to say that that’s not what *most* people have in mind.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that it isn’t valid for people to raise other concerns.

However, I think you are largely attacking a straw-man. As I admitted above, I recognize that there are situations where actors don’t seem to have preferences at all. But the rest of the concerns you raise are irrelevant. That preferences change does not violate HPWC. Nor does the fact that preferences vary from one actor to another. In fact, game-theorists frequently stress that the “utilities” to which they refer in their models are *subjective*. When and if it comes time to evaluate the observable implications of a model, scholars will focus on things that can easily be measured, but I’m not aware of (m)any game-theoretic models which assume that all actors want exactly the same thing, and the vast majority critically hinge upon the assumption that they do not.

Thanks for this interesting post. It certainly tells me a lot I didn’t know, however I can’t say that I’m altogether won over to RCT. For one thing, although it’s clear that RCT is able to accommodate models of subjectivity besides the stereotypical self-interested, timeless, utility maximising liberal subject it still appears that this specific model is utterly hegemonic within RCT (assuming that term can be taken to span political science, economics, behavioural psych, etc.). Why is it that this form of subjectivity is so widely assumed within RCT that people mistake it for being RCT’s essential, founding assumption? I think this remains a really important question.

Even if you pluralise RCT by allowing for a wider variety of rationalities and modes of choice, from the outside it still appears that RCT as a whole effects a flattening out and homogenisation of social life carried out according to a preconceived, narrow-minded and largely unchallenged ideal — that of the disembodied liberal subject. It reads all human action as utility maximisation and the effect of this is that (a) most human life is completely misunderstood and (b) that utterly false model is then recycled and imposed on human lives through the practical applications of behavioural psychology, economics, etc. Reading all human action as utility maximisation is not only false but those falsehoods are actually imposed on people as ‘correct’ models of action; we’re coerced into following them because that’s what some RC-based sciences have decided is the ‘rational’ way. This, of course, is because such advices are snapped up eagerly since they accord with the dominant ideologies of our day.

In other words, a degree of plurality within RCT doesn’t necessarily absolve the field from the criticisms usually aimed at it because the vast majority of its work seems to conform to these criticisms. RC in the broadest sense drives some of our most politically influential sciences. Economics alone plays a massive part in formatting human action according to its own idealisations. Just take a walk in a supermarket and see RC in action with regard to how everything is laid out according to ideal models of decision making.

So, I continue to believe that RCT in general is both deeply flawed and far too successful — and for largely the same reasons! That said, it does seem rather more interesting in the above iteration than in others I’ve encountered in the past.

Thanks for the response, Philip. You raise some important points.

I acknowledge that a considerable amount of work is guilty of making the types of assumptions you find problematic, but I’m not sure I’d say such approaches are hegemonic. Nor do I think that the fact that people believe such assumptions are intrinsic to RCT tells us much. The fact that “rational” means what it means in ordinary language predisposes people to assume that “rational choice theory” assumes certain things. One could easily imagine the stereotypes persisting even if the majority of “rational choice” work did not make the sorts of assumptions people associate with “rationality”. The counterexamples I linked to above are just a small sampling of what’s out there that doesn’t conform to the stereotype.

I’m not sure why you assert that utility maximization is false. Defined properly, it’s more appropriate to say that it’s tautological than false! I think you may be assuming that “utility” must be defined in a materialistic sense. It need not be.

Again, I do not dispute that the types of assumptions you find problematic are commonly made (though I wouldn’t go so far as hegemonic). I just think the concerns you raise offer a stronger basis for a calling on “rational choice” theorists to branch out than a criticism of the approach altogether. Again, I think we want to avoid telling people not to learn a language just because many of the people who currently speak it choose not to talk about topics they ought to talk more about.

This is an interesting post. I wish most game theory in political science followed the model of “counterintuitive behavior explained by structural conditions.” That being said, you are somewhat understating the assumptions required for a Bayesian game-theoretic model to work, and this makes you overstate the extent to which game theory is “relational”. In particular, you don’t discuss the common knowledge assumption (note, I’m not talking about complete information), which basically means that the parameters of the game must be defined before interaction occurs. If the parameters of the game shift during strategic interaction–or more specifically, if the parameters are redefined by the interaction itself–then game theoretic modeling is not possible (see Aumann and Binmore on this argument). So interested in structure, yes, but not in the same ways that many of us are (in particular, those of us interested in structural change). And this is one of the key points that Nexon and Jackson are making.

Second, I assume you’ve read MacDonald’s “Useful Fiction or Miracle Maker,” published in the APSR years ago? There’s a solid case to make that the “confusion” surrounding what “rational choice” means lies as much on theorists operating within that approach than its critics (and the fact is, your position that it is a useful fiction is only one possibility).

I wouldn’t recommend MacDonald’s paper because, as I remember it, he tends to try and discuss the issue in terms of the epistemological assumptions of RCT when in fact his discussion is almost exclusively focussed on the ontological assumptions. Mind you, this confusion is pretty endemic across PS and IR. I don’t disagree with much that you say. However, I still see two major points of disagreement. First, as I understand its’ theoretical articulation (which might be very different from how it’s practiced, but that raises the issue of whether the way it’s practiced is deserving of the label anyway) there are really two basic issues that are necessary. First, the agents are assumed to be utility maximers, and second the assumptions about the agents aren’t meant to be realistic. So yes, and I’ve often made the same point, RCT doesn’t actually believe that that’s all there is to people, just that it’s useful from a methodological perspective to treat them ‘as if’ they act that way. In that context, I can’t see why anyone who adopts an instrumentalist approach theoretical assumptions could then object to RCT. It’s different for the likes of Green and Shapiro, who like me, take a realist approach to theoretical assumptions. Incidentally, the point you raise about the structural properties has also been made by Colin Hay. I actually don’t have that much of a problem with RCT as one approach among many, but I do think the outcomes need to be supplemented by a more contextual analysis. It’s when it overstretches its remit that I get concerned, but then again I could say the same about most approaches. One final point, I’ not even sure it qualifies as a ‘theory’, rather than a method, but that would raise a whole set issues about what theory is; and I suppose the consistent instrumentalist would simply say ‘whatever is useful’.

Fair points, Colin.

I do indeed favor the “as if” interpretation, as do many “rational choice” scholars. As you say, that’s not going to be satisfactory to those who reject an instrumentalist view of assumptions, but should be pretty uncontroversial among those who do.

I think it’s eminently reasonable to supplement “rational choice” analyses with more contextual analysis.

There’s no question in my mind that RCT is not a theory in any sense of the word. I’m not even sure it’s a methodology. Game theory certainly is a methodology, and most of my comments so far have only focused on game theory, but it seems clear that the field considers other types of work to be “rational choice” as well. In fact, as far as I can tell, if a non-game-theorist uses the words “cost”, “benefit”, and “incentive” often enough, their work becomes “rational choice”, whereas those who insist that they are not rational choice scholars are taken at their word, regardless of whether their arguments implicitly make all the same sorts of assumptions. That’s one of the reasons I say that I don’t even know what the term means.

Good points, Stacie.

Many — not all! — critiques hinge upon incorrect statements about what one must necessarily assume about what individuals know or want, and I was primarily directing my comments towards this. But you’re absolutely right that game theoretic models require more than just each player individually satisfying the HPWC criterion I discussed above — they also require common knowledge, and, depending on the model, may also place restrictions on the ways in which the players react to new information. I should have discussed this. You’re also right that one important implication of this is that it is very difficult (though I wouldn’t say impossible — I think you’ve misinterpreted Aumann and Binmore slightly here) to model situations where the parameters are redefined by the interaction itself, and thus it is very difficult to model big structural changes. I clearly misunderstood Dan and PTJ on that point. As PTJ pointed out to me on Twitter, the examples I gave in the post are inter-active, but not truly relational or transactional. And that’s generally all that game theory can offer.

I have read MacDonald’s piece, and though I have some issues with it, you are also right that there’s a lack of agreement among “rational choice” theorists about many key issues. The viewpoint I laid out above is not uncommon, but I shouldn’t have given the impression that reflects a universal consensus among game theorists or “rational choice” scholars. It is indeed only one possible position.