In the Guardian this morning, Christof Heyns very neatly articulates some of the legal arguments with allowing machines the ability to target human beings autonomously – whether they can distinguish civilians and combatants, make qualitative judgments, be held responsible for war crimes. But after going through this back and forth, Heyns then appears to reframe the debate entirely away from the law and into the realm of morality:

The overriding question of principle, however, is whether machines should be permitted to decide whether human beings live or die.

But this “question of principle” is actually a legal argument itself, as Human Rights Watch pointed out last November in its report Losing Humanity (p. 34): that the entire idea of out-sourcing killing decisions to machine is morally offensive, frightening, even repulsive, to many people, regardless of utilitarian arguments to the contrary:

Both experts and laypeople have an expressed a range of strong opinions

about whether or not fully autonomous machines should be given the power to deliver

lethal force without human supervision. While there is no consensus, there is certainly a

large number for whom the idea is shocking and unacceptable. States should take their

perspective into account when determining the dictates of public conscience.

The legal basis for this claim is the Martens’ Clause of the Hague Conventions, which argues that the means of warfare be regulated according to the “principles of humanity” and the “dictates of the public conscience” even in the absence of previously codified treaty rules rendering a weapon or a practice unlawful. The Martens’ clause, inserted into the Hague Conventions as sort of a back-up clause for situations not foreseen by the drafters, reads:

” Until a more complete code of the laws of war is issued, the High Contracting Parties think it right to declare that in cases not included in the Regulations adopted by them, populations and belligerents remain under the protection and empire of the principles of international law, as they result from the usages established between civilized nations, from the laws of humanity and the requirements of the public conscience. “

Now, previously I posted some quantitative survey data suggesting there is indeed widespread and bipartisan public opposition in the US to the idea of machines killing humans. But what can a qualitative analysis of open-ended survey answers tell us about the nature of that opposition? Does public opposition to the weapons include a sense of “shock” or concern over matters of “conscience”?

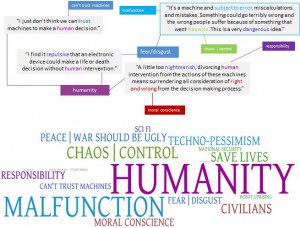

An initial qualitative break-down of 500 respondents’ open-ended comments explaining their feelings suggests the answer may be yes. The visualization below is a frequency distribution of codes used to sort open-ended responses by the 55% of respondents who “somewhat” or “strongly” opposed autonomous weapons, along with some representative quotations that illustrate how the codes were applied.

[Click the image for a clearer picture.]

Some caveats:

1) This survey captures US public opinion only. It is likely that by “dictates of the public conscience” diplomats were referring to global public opinion, so this study would be most useful if replicated in other country settings. Still, to the extent that US policymakers are making decisions about development of autonomous weapons or their position with respect to an international ban movement, they are required under international law to take US public opinion into account.

2) This is a preliminary cut at coding, and the results may change as the rest of the data-set is annotated more rigorously. But even this initial cut at the raw data illustrates the ways some Americans describe their intuitive concern over autonomous weapons. There is certainly an “ugh” factor among many respondents. There is a concern about machine “morality” and reference to a putative warrior ethic that requires lethal decision-making power to be constrained by human judgment. But primarily, there is a sense of “human nationalism,” whether rational or not: the notion that at a moral level certain types of acts simply belong in the hands of humans, that outsourcing death is “just wrong.”

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

Intriguing, but I am not yet convinced that any kind of survey instrument is either necessary or sufficient to concretize the notion of the “public conscience.”

(Lots of Americans seem to have believed that Saddam Hussein had something to do with 9/11, after all. The public might — might — be in some sense rational, but that doesn’t mean it’s especially well-informed.) Personally I’d put more weight on opinio juris than vox populi here. Can anyone coherently argue *for* autonomous targeting? *Does* anyone? If they do, what’s the reaction like? That’s where I would look in order to see what the Martens clause does or doesn’t permit on this issue. It’s not the aggregated individual opinions that matter here, but the common sense of the group — which is only imperfectly reflected in what particular individuals think.

Fair enough. But I think that’s what the Martens clause was meant to capture – people’s irrational, gut sense of right or wrongness which is, after all, part of what makes us human therefore the language about “principles of humanity.”

“Personally I’d put more weight on opinion juris rather than vox populi here.” Well not being a historian of the Hague era I’m not sure, but I think the ‘public conscience’ notion in the Martens clause was actually specifically meant to treat the irrationally ‘humane’ impulses of the masses as a check on the sometimes calculatingly inhumane preferences of political and military elites. That said, it is important to note that if you treat the better educated, higher income, and more interested in news and public affairs as proxies for “elite” in the survey you’ll actually see even greater concern over AWS among those groups than among the wider public.

“Can anyone coherently argue for autonomous targeting? Does anyone?” They can and they do, how coherently is the subject for a future blog post in this series. :) Stay tuned.

Looking forward to more in the series.

My objection, I suppose, is only to the equation of public opinion data with the notion of the “public conscience.” But that’s what you’d expect a social constructivist to say, right? ;-)

The idea of autonomous weapons is not as frightening to some: if you command a military force you are already trusting autonomous (human) agents to carry out commands, including the command to kill (or not). I’ve already seen the argument that autonomous weapons are less likely to “malfunction” than their human counterparts. It’s not so much a matter of trusting the machines as it is of not trusting the soldiers. I have already seen some of the roboticists make the claim that a robot is less likely to violate the laws of war.