In all the media frenzy over “killer robots,” Terminator imagery comes up a lot. So do references to Battlestar Galactica. So does a specific scene from Robocop, soon to be remade to resonate with public fears of domestic drones.

In all the media frenzy over “killer robots,” Terminator imagery comes up a lot. So do references to Battlestar Galactica. So does a specific scene from Robocop, soon to be remade to resonate with public fears of domestic drones.

These iconic narratives invoke a recurrent theme in American science fiction about lethal robot malfunctions or uprisings against their human creators. So prevalent is this theme in anti-killer-robot media coverage that some have argued concern over autonomous weapons is a product of science fiction itself: Hollywood is apparently to blame for priming the public with an unfounded fear of killer machines. For example Joshua Foust writes:

“Why is there such concern? Part of the reason, arguably, is cultural. American science fiction, in particular, has made clear that autonomous robot are deadly. From the Terminator franchise, the original and the remake of Battlestar Galactica, to the Matrix trilogy, the clear thrust of popular science fiction is that making machines functional without human input will be the downfall of humanity. It is under this sci-fi ‘understanding’ of technology that some object to autonomous weaponry.”

There are several reasons why this sort of argument doesn’t make sense, but one of the most important is that it overstates the case about robopocalypticism in American “killer robot” science fiction. In fact, co-existing with the imagery of killer robots run amok is a broad range of far more benign killer robot imagery that no one seems to mind or even think about when worrying over autonomous weapons. Here are five great examples of killer robots filmmakers and TV producers definitely want you to want on your side in a pinch. [BSG SPOILER ALERT]

Lieutenant Commander Data. Ok, he’s an android not a robot, but this is mainly a cosmetic difference. As a man-made artificial intelligence capable of acting autonomously and carrying side arms like any other Starfleet officer, Data meets the definition of an autonomous armed robot soldier. And he is as lethal as anyone: his body count in the movie Nemesis alone is five dead (not including himself). Just think of how many life forms he has phasered, blown up or torpedoed during the series and other films not to mention the books and other spin-off media. Data also has a disturbing propensity to malfunction and has even been known to consider treason against the Federation and humanity (though, only for 0.68 seconds). Then again, he likes to paint, play dress-up and stroke his pet cat. Who wouldn’t want to head into the perils of uncharted space without him on board?

Lieutenant Commander Data. Ok, he’s an android not a robot, but this is mainly a cosmetic difference. As a man-made artificial intelligence capable of acting autonomously and carrying side arms like any other Starfleet officer, Data meets the definition of an autonomous armed robot soldier. And he is as lethal as anyone: his body count in the movie Nemesis alone is five dead (not including himself). Just think of how many life forms he has phasered, blown up or torpedoed during the series and other films not to mention the books and other spin-off media. Data also has a disturbing propensity to malfunction and has even been known to consider treason against the Federation and humanity (though, only for 0.68 seconds). Then again, he likes to paint, play dress-up and stroke his pet cat. Who wouldn’t want to head into the perils of uncharted space without him on board?

R2D2. That is right. Everyone’s favorite pet side-kick bot is also a lethal autonomous machine. While his primary job is a mechanical support droid, he is also fitted with a “shock arm” that uses an electric charge to stun victims – an act that while non-lethal in theory can kill depending on the health of the victim’s heart and nervous system. R2 has also been known to harm humans by throwing other droids on them and opening trap doors under their feet, to destroy ships, and to provide close combat support in numerous other missions. According to Wookiepedia R2 often “fought on the front lines” with Anakin during the clone wars and was responsible for the destruction of the entire planet Byss. Yet R2D2 is framed as cute, cuddly, and always on the side of good, so we barely recognize him as the potentially lethal robot he is.

R2D2. That is right. Everyone’s favorite pet side-kick bot is also a lethal autonomous machine. While his primary job is a mechanical support droid, he is also fitted with a “shock arm” that uses an electric charge to stun victims – an act that while non-lethal in theory can kill depending on the health of the victim’s heart and nervous system. R2 has also been known to harm humans by throwing other droids on them and opening trap doors under their feet, to destroy ships, and to provide close combat support in numerous other missions. According to Wookiepedia R2 often “fought on the front lines” with Anakin during the clone wars and was responsible for the destruction of the entire planet Byss. Yet R2D2 is framed as cute, cuddly, and always on the side of good, so we barely recognize him as the potentially lethal robot he is.

Optimus Prime. Actually, any Autobot. Though whether they count as robots could be debated, they are definitely lethal. Sure, unlike the Decepticons they do their best to avoid harming humans, but who really believes they do not unleash some serious collateral damage in their struggle for galactic justice? Yet undoubtedly these are just warriors with whom we are meant to ally and sympathize.

Optimus Prime. Actually, any Autobot. Though whether they count as robots could be debated, they are definitely lethal. Sure, unlike the Decepticons they do their best to avoid harming humans, but who really believes they do not unleash some serious collateral damage in their struggle for galactic justice? Yet undoubtedly these are just warriors with whom we are meant to ally and sympathize.

Sharon “Athena” Agathon. Her race may be genocidally bent against humans, but “Athena” does the fleet a solid on more than one occasion – sharing intel, disrupting Cylon viruses, and blasting old Cylon models and new. And as long as she is on our side, we are happy to make sure she has a uniform and sidearm. We even get warm and cuddly when she falls in love with one of us and get annoyed at her detractors. We feel good when our just warriors protect her from harm at the hands of human war criminals because though she is a killer and a robot (of sorts) we are asked to see her as one of us.

Sharon “Athena” Agathon. Her race may be genocidally bent against humans, but “Athena” does the fleet a solid on more than one occasion – sharing intel, disrupting Cylon viruses, and blasting old Cylon models and new. And as long as she is on our side, we are happy to make sure she has a uniform and sidearm. We even get warm and cuddly when she falls in love with one of us and get annoyed at her detractors. We feel good when our just warriors protect her from harm at the hands of human war criminals because though she is a killer and a robot (of sorts) we are asked to see her as one of us.

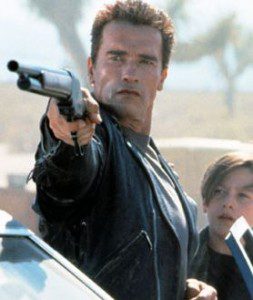

Good Terminator. Fascinatingly, perhaps the best example of a “good killer robot” comes from the same meta-verse as the image that has come to define the anti-killer-robot campaign: Terminator. But not the mean Terminator of the original film. We are talking the good, reformed Terminator of Terminator_2:_Judgment_Day. He looks the same, only he will put himself in between bad guys and “womenandchildren” instead of killing them. All the machine needed was the right programming and it could go from ruthless heavy metal assassin to noble protector. It even embodies just warrior principles to point of sacrificing itself – in a vat of molten lead – to protect the human future.

Good Terminator. Fascinatingly, perhaps the best example of a “good killer robot” comes from the same meta-verse as the image that has come to define the anti-killer-robot campaign: Terminator. But not the mean Terminator of the original film. We are talking the good, reformed Terminator of Terminator_2:_Judgment_Day. He looks the same, only he will put himself in between bad guys and “womenandchildren” instead of killing them. All the machine needed was the right programming and it could go from ruthless heavy metal assassin to noble protector. It even embodies just warrior principles to point of sacrificing itself – in a vat of molten lead – to protect the human future.

Are there good reasons not to outsource kill decisions to machines? Absolutely. Is that concern being trumped up by or primarily a result of the “killer robot” film industry? I am unconvinced. These examples suggest that “killer robot” fiction is not always portrayed as robopocalyptic, that there is great variation in American’s literary relationship between robots, lethality and military ethics on TV and in film, and that the more interesting question is why a particular iconic discourse of killer robot uprisings has become so politically salient today given the diverse cultural repertoire of narratives on offer from Hollywood. That, I suspect, has to do with people’s general worry about the ethics of autonomous killing. What do readers think?

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

Charli, Great post. A few hurried thoughts…

Most of the examples cited seem to be part of a Pinocchio complex in which the robot or android really desires (or is programmed to want) to be “human” and so their killing is excused in the narrative. So these exceptions don’t seem so exceptional.

Nevertheless, my hunch is that the real fear is not about robots per say but mechanized slaughter or genocide without conscience. I would agree that this can’t be blamed solely on Hollywood. The first instance of this fear in popular science fiction pre-dates Hollywood as H.G. Wells published War of the Worlds in 1898. Wells’ book was essentially a reversal and generalization of the Tasmanian genocide conducted by Europeans.

I would argue that these fears are almost never about technology but expressions of guilt by an empowered group about historical imperialism and race/class/gender oppression.

These are the options that the sci-fi genre leaves us with: of creating autonomous machines that marginally improve the condition of mankind (Data, R2D2) while also risking the destruction of mankind (the threat tends to be averted by other machines at the last second… very risky) or not creating autonomous machines, no one would opt to create the machines in the first place. I’d say the sci-fi genre clearly leaves us with the impression that autonomous machines are going to be the end of us all. Whether this informs people’s opposition to autonomous weapons, I couldn’t say,

Lieutenant Commander Data is an interesting example of a good android, as his creator also created “Lore”, an android with Data’s exact capabilities but with a penchant for doing evil. Data also had another twin, B-4, who although good-willed was corrupted by the Remans and used against the Federation.

It complicates matters, I suspect, if these good killer robots are only good because they kill bad killer robots. That seems to on balance suggest that killer robots are bad (the T3 and Shannon examples at least).

I think you have a point. But then again you have examples like The Doctor on Voyager who (as an artificial life form) is capable of and did make the decision to seal two crewmen in a Jeffries tube to their deaths for the good of the ship. Again, a good “killer AI” killing humans and not even bad humans but for good reasons, and one portrayed as operating within the bounds of acceptable human behavior. I suppose a lot depends on whether we are encouraged to see specific AI as sentient life forms (e.g. the Doctor and / or Data) v. “mere” machines. Still I think it begs the question of what it is people are fundamentally, viscerally afraid of. And I would posit, again playing devil’s advocate, that pop culture – at least in cult films and TV shows if not blockbusters – is doing an interesting job of playing with those contradictions rather than merely sensationalizing. If I’m wrong, what else am I missing?

I agree that sci fi does complicate the picture. But, I am not sure if the Doctor is a Robot (its a hologram) and Data might be balanced by Lore, his evil brother, who then tries to give the ship over to the crystalline entity. I will grant though that Data is on balance a good role model for future killer robots.