Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Eric Grynaviski, who is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at George Washington University.

The recurring debate on this blog has centered on some of the bigger themes about the relationship between rational choice theory and game theory. I argued in an earlier post that when one focuses in on the specific logic of rational choice theory and/or game theory, getting away from its abstract characterizations, there are some similarities about the way it understands society with alternative approaches.

In this post, I want to focus on a more specific issue, which is how to understand the relationship between pragmatism and rational choice theory. Pragmatism has recently been used in IR in two ways. On the one hand, pragmatism has been invoked to justify a particular image of science, usually (but not always) one that is post-paradigmatic or pluralistic. Others have concentrated on the pragmatist contributions to IR theory or ethics.

This post concentrates on pragmatism as social theory. The early pragmatists—Dewey and Mead in particular—were very interested in questions such as logics of action that are at the heart of modern-day IR theory. I want to argue that there are a lot of similarities between pragmatism and rational choice theory, providing at least one via media between sociological and economic approaches that has been unexplored to date.

There are significant differences though between the ways rational choice theory and pragmatism tend to model learning and reasoning. The nub of the problem that this post concentrates on is uncertainty. Rational choice theorists tend to describe some set of possible worlds (a state space) over which agents assign probabilities. Reasoning and learning usually involves agents changing those probabilities in response to new information. Pragmatists tend to be interested in why possibilities become possible or become impossible; they are interested in how states enter and leave the state space and not how probabilities are assigned.

This post concentrates on two issues. Conceptually, is a rational model of action compatible with a pragmatist theory of action? And second, what are the differences in their treatments of certainty.

A Pragmatic Theory of Action. What is a pragmatic theory of action? Building on the classical pragmatists, I take a pragmatic theory of action to hold that:

- Individuals usually do not think about their beliefs. When individuals are engaged in actions, they rarely reflect on their beliefs about actions so long as the action produces the expected results. We can call this, using Dewey, a normal situation.

- When individuals’ actions do not produce their expected results, then there is an ‘irritation of doubt’ that leads them to (hopefully) experiment, revising their beliefs, and adopting new courses of action.

- When individuals’ new actions produce expected results, individuals then settled into unreflective action once again.

The quintessential example from Dewey is the way he dealt with his kids. Dewey let his kids experiment to test the consequences of their actions rather than telling them what to do. One day, so the joke goes, Dewey was found walking with his kids in the snow down the street without their shoes on. He thought that they would realize that the consequences of their belief that shoes were unnecessary would quickly become untenable, leading them to demand shoes when it’s cold. This is the nature of his view that life is an experiment; even walking in the snow.

The quintessential example from Dewey is the way he dealt with his kids. Dewey let his kids experiment to test the consequences of their actions rather than telling them what to do. One day, so the joke goes, Dewey was found walking with his kids in the snow down the street without their shoes on. He thought that they would realize that the consequences of their belief that shoes were unnecessary would quickly become untenable, leading them to demand shoes when it’s cold. This is the nature of his view that life is an experiment; even walking in the snow.

And,

- In dealing with social action or political action, the crucial beliefs are the beliefs about what others will do in response to our actions.

In other words, in the social world, learning is triggered when people say or do things that we don’t expect. In these cases, we rethink what we believe to be possible. Our assumptions—the beliefs that we hold with certainty—are cast into doubt by people we simply do not understand.

The specific social nature I explore in the next blog post. Here I want to concentrate on 1-3. What beliefs are important here? The crucial question is whether agents’ current beliefs include a belief in a possible state of the world that explains the consequences of an action. In Dewey’s kids in the snow example, the crucial question is whether Dewey’s kids believe that there are two possible states of the world—one in which snow hurts bare feet and one in which snow does not hurt bare feet—or whether they believe that there is one possible state (snow doesn’t hurt bare feet). If there are two possible states of the world, then Dewey’s kids do not need to drastically rethink their beliefs when they discover one is false: they simply learned. In the latter case, the kids need to reconsider states formerly thought impossible (that shoes could in any way be good). In other words, the irritation of doubt is triggered in the latter case, forcing consideration of the impossible, but not in the former.

With this cursory account of pragmatism, this post asks whether this is consistent with rational choice theory and/or game theory.

Rational Choice Theory:

The stock definition of rational choice theory is that rational choice theory describes rational action as a case where an individual selects a strategies that they believe will maximize the utility of their action, can order their preferences, and their preferences are transitive. Instead of trading on these stock definitions, I take Ariel Rubenstein’s formulation that rationality requires a person to ask three questions before making a decision:

- What is feasible?

- What is desirable?

- What is the best alternative according to the notion of desirability, given the feasibility constraints?

Pragmatism, in one sense, might be thought to deny that individuals ask these questions. This view might reflect pragmatists’ reluctance to believe that individuals think through most of their decisions because of (1) above: most of the time, I never consider alternative strategies for getting to work, negotiating with an ally, or behaving in an institution. So long as the patterns of action that I habitually engage in produce results that work, I do not think through new ideas or strategies. This is an extreme version of Simon’s bounded rationality. Simon argues that there are too many possible decisions, and therefore individuals economize by only evaluating a few. The pragmatist view in its strongest form, in contrast, is that individuals almost never make decisions on almost any matter of substance. They never ask what is feasible and what is desirable.

While most actions, for pragmatists, do not meet the definition of rationality, actions that take place in ‘problematic situations’ are strong candidates for rational analysis. When a routine is disrupted because an action does not lead to its intended consequences, I rethink what is feasible and desirable, and rationally adapt my behavior to a new routine that is likely to lead to better results. If a state expects another to reciprocate a cooperative gesture, for example, but instead finds confrontation where cooperation was expected, it reflects on its interests and available strategies, trying to figure out what went wrong and how to get the intended results next time.

Game Theory:

To model pragmatic social action, at least two major revisions are needed to the normal way that human behavior is modeled. The first—related to uncertainty—is discussed in this blog post. The second—related to the irritation of doubt and learning the impossible—is discussed in the next.

First, uncertainty. Pragmatism denies that agents usually act under the kinds of uncertainty that Bayesian interpretations of human action propose. This is consistent with Mitzen and Schweller’s argument that there is an uncertainty bias in IR theory: agents are nowhere near as uncertain about the world as most rationalists suppose. Most members of the Obama administration, for example, are likely certain that certain things are impossible: the prospect that terrorists do not plan attacks on American soil, that Putin plans on improving Russia’s human rights record, or that the Republic Party intends to work in a bipartisan fashion after the midterm election.

If actors are certain that some strategies are impossible, then Bayesianism is difficult. One reason is that If an agent believes that some course of action has a 0% chance of taking place—if they are certain it will not occur—then Bayesian updating is inappropriate because agents cannot update from a prior probability of 0%. More fundamentally, game theory tends to think about reality as a set of possible worlds, where possible means that agents believe that there is some possibility that an event is true. This state space—the possibilities available for actors to consider—is rarely the direct treatment of attention in IR. How is the state space constructed, and how do states enter or leave the state space?

The first question is how states leave the state space: how do possible interpretations of events become impossible?

Here, some connection between pragmatism as an intellectual foundation for formal theory shows some promise. To illustrate how agents reason about possibility and impossibility, I suggest using Kripke structures. Kripke structures are a fun (and happily visual) way of thinking about learning that is different from traditional Aumann structures. Before going through this argument, I want to be clear that I will argue that understanding reasoning through Kripke structures is consistent with thinking about relationships, such as constitutive relationships, and how these relationships affect learning; Kripke structures, however, do not exhaust the ways we can think about these issues.

An example. To illustrate, I use a revised version of the canonical Muddy Children’s Puzzle (or Wizard with Three Hats), to show the power of this process of reasoning in a more elaborate context. Imagine that three diplomats, representing three different states meet. Each diplomat knows that a war is looming, but no diplomat knows whether their own state is the target for a military strike. Further, each diplomat has access to intelligence information on whether the other two states are targets but does not know if it is a target.

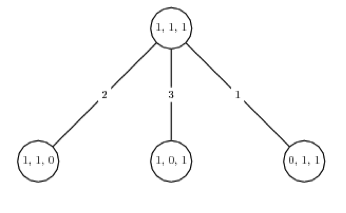

The result is that there are eight possible states of the world: (1,1,1), (1,1,0), (1,0, 1),(0,1,1),(1,0,0),(0,1,0), (0,0,1), and (0,0,0) where the (x,y,z) represent three different states and 1 = target and 0 = not a target (i.e. 1,1,0 means that x and y are targets but not z). In short, any state or combination of states may be a target. The Kripke structure modeling the possible states of the world is represented here:

Now, each diplomat wants to figure out whether their own state is a target and is willing to sincerely share information with the other diplomats in order to determine their own status. If they could directly share information, it would be easy to discover whether one is a target. However, it is considered treason to simply tell the other whether they are a target, because that would explicitly reveal confidential intelligence information. How can they figure out if they are a target if no diplomat is willing to tell them that they are, or are not, a target?

One diplomat, who has a mathematical background, suggests a series of questions in which all three diplomats respond simultaneously. The question in each round is: “Do you know if you are a target?” By the end of two rounds, the diplomats are sure to discover whether they are a target. The other two diplomats do not understand, and the mathematically inclined one takes out a pen and paper and begins to explain.

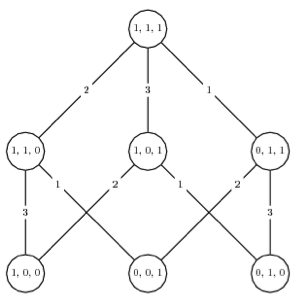

“Initially, there are eight possible states of the world. But, we know that war is looming so at least one state must be a target, this is common knowledge. Thus, the eighth possibility (no target) is impossible. Therefore, there are seven possible states of the world.” The diplomat then draws the new figure.

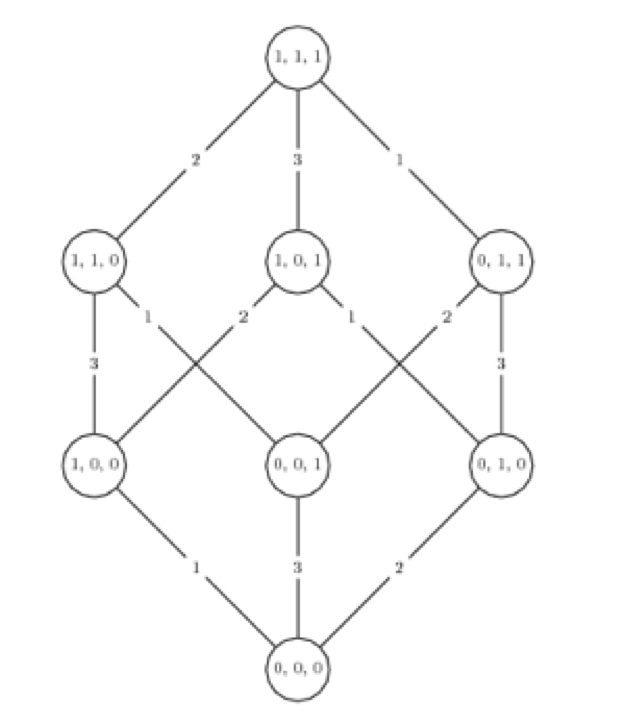

The diplomat continues, “Now, if know that the other two diplomats’ states are not targets, then you would respond ‘yes’ to the question ‘do you know you are a target’ because that means that you are the target [we know someone is the target and if neither of the other two is a target then it must be you]. Then the rest of us will know that we are not targets. If everyone answers no, then we all know that there must be at least two targets (because if there was only one, someone would have figured out who it was). Thus, after the first round of questions, we eliminate three more states of the world.” The diplomat then draws another figure:

The diplomat goes on: “At least two of us must be targets. When I ask ‘do you know if you are a target,’ you will respond yes if only one of the others is the target, and respond know if both of the others is a target. You can respond yes if only one is a target because you know that there are at least two targets and if only one of the others is a target, which means you are also a target. You can respond no if both are targets because you remain unsure whether there are two or three targets in sum. If we all answer no, then we know that only one state of the world is possible.”

The diplomat goes on: “At least two of us must be targets. When I ask ‘do you know if you are a target,’ you will respond yes if only one of the others is the target, and respond know if both of the others is a target. You can respond yes if only one is a target because you know that there are at least two targets and if only one of the others is a target, which means you are also a target. You can respond no if both are targets because you remain unsure whether there are two or three targets in sum. If we all answer no, then we know that only one state of the world is possible.”

He draws a final picture:

“We are all targets.” Through this process, if they each answer the question truthfully and simultaneously, then the diplomats can learn, at most after two iterations, what state of the world exists.

In examples such as this, players are updating their beliefs over time, but they are updating their beliefs about what states of the world are possible, not probable.

1914. The basic ideas underlying this argument I believe to be more relevant to IR, especially to discussions of signaling, then many of the current approaches that emphasize updating probabilities. Consider the example of the French before the First World War. On Tuchman’s account, France worried that if Britain believed it was the aggressor, then Britain would not send troops to France to fight the Germans. Therefore, the French needed to do something that to close off the possibility that the British believed that French aggression could occur in any possible world. To do so, they pull their troops back from the front a bit, forcing the Germans to clearly be the aggressors by attacking into French territory. The Kripke structure of the world before the First World War is M = (S, p, K1, K2), where S includes {(0,0), (1,0),(0,1), (1,1)}, where 1 indicates aggression and 0 indicates non-aggression, and France is player 1 and Germany is player 2. (1,0) here means that the French are aggressive and the Germans are not. This is represented graphically below:

The British, hypothetically, are unsure which state of the world exists. The French and/or the Germans may initiate the war: both have troops headed toward the front. The French worry that if a war begins, the British will not be able to distinguish between the states of the world {(1,0),(0,1),(1,1)}. If these states are indistinguishable, then the ambiguity may be used by opponents of Anglo-French relations to maintain British neutrality. The French decide upon a dramatic signal to remove two states of the world from the set of possible states: they withdrawal their troops from the front. This gesture does not increase the possibility that the French are aggressive: it cleaves off two states of the world from the state space (those in which the French and Germans are both aggressive, and in which the French are aggressive and the Germans are defensive.

Rethinking Uncertainty. The key point all of these examples are trying to make is that people often reason from ‘certainty’: they are certain that some set of worlds is possible given the information that they have, and they cannot assign probabilities to some state of the world. This is consistent with the pragmatic view that people rarely ‘doubt’ the beliefs that are the premises for actions that they pursue. This has important implications. First, it may provide a more realistic account of action, not rooted in probabilities, that helps explain important cases. Take the example of the Bush administration and WMD in Iraq. The Bush administration believed that there could be WMD in Iraq and insisted on direct evidence that the weapons were not there. In the language of probabilities, this is ridiculous: the consistent failure of evidence to prove that weapons exist should have made the probability that the weapons exist become low enough that the costs of war, no matter how small, outweighed the risk (see this paper for a contrary argument). In the language of possibility, the Bush administration worried so long as the weapons were possible: they reasoned from possibility and not probability.

Second, when communicating with others, agent may not try to increase the likelihood that some state of the world is true, which is the canonical view in the signaling literature, but try to convince them that it must be true.

Second, when communicating with others, agent may not try to increase the likelihood that some state of the world is true, which is the canonical view in the signaling literature, but try to convince them that it must be true.

Moreover, emphasizing possibility over probability has the convenient feature that it looks to the constitutive rules for understanding state behavior that are also at the heart of constructivist concerns. In the above example, to understand how the state space is modified may (in some applications) require understanding the constitutive features of the state space: what types of possibility relations exist between state spaces?

Finally, the most self-serving implication though is its sets up part two of this post which doesn’t make sense without part 1: what prompts the irritation of doubt in the social world that leads agents to rethink their beliefs, and how new beliefs are fixed. If there are no possible states of the world that explain an action, then we need to rethink our beliefs because some impossible state must be true.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Not convinced about the consequences of the snow/shoe example, but as long as you end up here, I’ll leave you alone for now….’First, it may provide a more realistic account of action, not rooted in probabilities, that helps explain important cases.’ :)

Thanks Colin,

The reason I like that example–although its maybe not right for this post–is that it points out that the thinkers who defended experimentation early in the 20th century had a richer theory of what experiments were (‘life is an experiment’) than modern political science. The snow example I think captures some of that.

Hi Eric, yes I can see that, and in that context I think you are right. I think the difference though, and something Dewey would probably insist on is that that process of experimentation in science has to be much more systematic than in the notion of ‘life as an experiment’. But I don’t think that affects the broader argument you have here, and I’m pretty much in agreement on that.

I agree that this is a side issue. But I might say that Dewey would likely reject any strict division between ‘science’ and other areas of social life, or at least that he would reject any strict division rooted in the idea that the sciences were experimental and other fields or parts of social life more generally are not.

But yes, Dewey (and especially Peirce) would have much to say about social science experiments (if they have dreamed anyone would perform them), arguing for standards. This would likely be mainly Peirce though, who wrote about randomization before it had been performed in any almost science. Dewey always seemed less concerned with methods to me, and more concerned with broadening the areas in which the basic ideas underlying science made sense in modern life. It was a more progressive vision.

Sorry for the confusion. This is a GUEST POST by Eric Grynaviski.

This is a very interesting post! Your discussion of a pragmatic theory of action reminds me a great deal of Gross’s pragmatic theory of social mechanisms, and Kripke structures are both an awesome thing and a thing I didn’t know about.

But I’m a bit confused about where the Kripke structures help us better understand how people approach uncertainty. Let’s accept that people do not calculate probabilities with the scope presumed by rat-choice. Let’s also accept that people do actually reflect upon problematic situations, and that (pace Bourdieu) strategising isn’t merely a second-order, tactical process but a genuine cause for the envisioning of new possibilities for action. In the first example you give, actors are initially unable to adjudicate between multiple possible worlds. Okay. So first of all, in this example the actors correctly assume probabilities of 0 or 1 to all possible worlds, rather than start from set already constrained by the sub-intentional dispositions that pragmatists think animates most normal situation actions and which would presumably be amenable to sociological analysis. Second, only by a stroke of luck is a mathematically inclined diplomat able to employ a method for reducing uncertainty. So in this case, two diplomats engaged in no problem-solving, and a third employed an existing tool in a relatively standard way. This doesn’t seem to be a case of experimentation or innovation.

Actually, the two things which I find most intriguing about the example have nothing to do with the process by which the three diplomats were able to systematically employ a formal calculus to ascertain truths about the world. First, I want to know what brought them to the table in the first place. If the one diplomat had the mathematical tool, but not the information, how did she convince the others to provide that information. Second and more specifically, how did these diplomats realise that they could overcome the prohibition on sharing classified intelligence by using this mathematical tool? These two linked questions seem to me to be the sort of puzzles that would be best approached through a pragmatist analysis. They involve the manipulation of existing norms, which is right in line with the symbolic-interactionist tradition that Mead generated, and they imply that some actor(s) did something creative to resolve a problem through strategic interaction (incidentally the title of another famous symbolic-interactionist’s engagement with game theory).

Please excuse me if this seems pedantic or long-winded. I am in fact delighted to read your thoughts, as I am very interested in approaching my own research from pragmatist foundations and you are obviously much more sophisticated in your own methodology.

Good questions, thanks. Part of these will be discussed in part 2. In general, these comments are interesting because they highlight differences between the ways in which pragmatists thought about these questions, from the ways in which continental thinkers approach the same issues. I am not saying that American pragmatism has it ‘right’, but its important to recognize some differences. Hans Joas’s Pragmatism and Social Theory is nice on much of this.

First, the example may be a bit misleading; I tried to make it cute for IR purposes. The main formulation is below:

Several children are playing together outside. After playing they come inside, and their mother says to them, at least one of you has mud on your head. Each child can see the mud on others but cannot see his or her own forehead. She then asks the following question over and over:

can you tell for sure whether or not you have mud on your

head?

The wizard with three hats formulation is here: https://www.greylabyrinth.com/puzzle/puzzle007 . I know some people prefer it.

In this example, the questions you have about the diplomat and math aren’t quite relevant, or how the kids got to the table. I was trying to be cute by having the diplomat explain, rather than the kids spontaneously reason which is standard. As you point out, these elements may be misleading.

Regarding your first questions, they way I am trying to use the Muddy Children’s Puzzle is to show that learning in a rational model can ignore uncertainty in some cases. This is the central point I am trying to make, which is consistent with a generally pragmatic theory (for me). You are asking the sensible next question: is this a normal situation or a problematic situation? I would argue that in the canonical formulation its a problematic situation because the kids start out believing that no one can figure out they were playing outside. This triggers a reexamination of their beliefs, and the creation of 8 or so possible states of the world. Through a process of experimentation, where the ‘treatment’ if you will is asking and replying to a question, they fix on a new belief.

This is not an example where the kids need to be overly creative, its true. I suspect for many pragmatists, we often do not need to be creative though. If I go to dinner believing pickle taste food, and then eat a pickle and discover I am wrong, I need to refit my beliefs and there are some possibilities (pickles are always bad, this pickle is bad, some class of pickles is bad). There is creativity here (and certainly sets up interesting pickle-eating experiments), but certainly not the kinds of bricolage interesting to Bourdieu and others.

Regarding dispositions, I am not sure if there is a direct analog in pragmatic thought, in part because for B, dispositions are in part produced by social position. For Dewey at least, social position does not heavily figure in the analysis. Instead, the crucial questions are in essence whether there is a received idea that is used successfully as the basis for action for some period, and then whether the agent is able to reflect on that belief given her social environment (is there evidence that the belief is problematic?). This may be a shortcoming because position isn’t immediately relevant. But, this is closer to the topic of the next post where we have problems of difference: agents with different beliefs who are interacting.

Good questions, thanks. Part of these will be discussed in part 2. In general, these comments are interesting because they highlight differences between the ways in which pragmatists thought about these questions, from the ways in which continental thinkers approach the same issues. I am not saying that American pragmatism has it ‘right’, but its important to recognize some differences. Hans Joas’s Pragmatism and Social Theory is nice on much of this.

First, the example may be a bit misleading; I tried to make it cute for IR purposes. The main formulation is below:

Several children are playing together outside. After playing they come inside, and their mother says to them, at least one of you has mud on your head. Each child can see the mud on others but cannot see his or her own forehead. She then asks the following question over and over:

can you tell for sure whether or not you have mud on your

head?

The wizard with three hats formulation is here: https://www.greylabyrinth.com/puzzle/puzzle007 . I know some people prefer it.

In this example, the questions you have about the diplomat and math aren’t quite relevant, or how the kids got to the table. I was trying to be cute by having the diplomat explain, rather than the kids spontaneously reason which is standard. As you point out, these elements may be misleading.

Regarding your first questions, they way I am trying to use the Muddy Children’s Puzzle is to show that learning in a rational model can ignore uncertainty in some cases. This is the central point I am trying to make, which is consistent with a generally pragmatic theory (for me). You are asking the sensible next question: is this a normal situation or a problematic situation? I would argue that in the canonical formulation its a problematic situation because the kids start out believing that no one can figure out they were playing outside. This triggers a reexamination of their beliefs, and the creation of 8 or so possible states of the world. Through a process of experimentation, where the ‘treatment’ if you will is asking and replying to a question, they fix on a new belief.

This is not an example where the kids need to be overly creative, its true. I suspect for many pragmatists, we often do not need to be creative though. If I go to dinner believing pickle taste food, and then eat a pickle and discover I am wrong, I need to refit my beliefs and there are some possibilities (pickles are always bad, this pickle is bad, some class of pickles is bad). There is creativity here (and certainly sets up interesting pickle-eating experiments), but certainly not the kinds of bricolage interesting to Bourdieu and others.

Regarding dispositions, I am not sure if there is a direct analog in pragmatic thought, in part because for B, dispositions are in part produced by social position. For Dewey at least, social position does not heavily figure in the analysis. Instead, the crucial questions are in essence whether there is a received idea that is used successfully as the basis for action for some period, and then whether the agent is able to reflect on that belief given her social environment (is there evidence that the belief is problematic?). This may be a shortcoming because position isn’t immediately relevant. But, this is closer to the topic of the next post where we have problems of difference: agents with different beliefs who are interacting.

This is a helpful response, and I’ll definitely be looking forward to your next post.

Doesn’t it seem to you as though the non-reflective nature of normal action in pragmatism bears some similarity to the dispositional nature of action in Bourdieu? Even if social position is not invoked to explain those dispositions in the former, I am not sure why it couldn’t be. The difference seems to be that pragmatists are theorising a cognitive mechanism for reflection while Bourdieu is leaving psychology out entirely, for the most part.

This is a helpful response, and I’ll definitely be looking forward to your next post.

Doesn’t it seem to you as though the non-reflective nature of normal action in pragmatism bears some similarity to the dispositional nature of action in Bourdieu? Even if social position is not invoked to explain those dispositions in the former, I am not sure why it couldn’t be. The difference seems to be that pragmatists are theorising a cognitive mechanism for reflection while Bourdieu is leaving psychology out entirely, for the most part.

This is a helpful response, and I’ll definitely be looking forward to your next post.

Doesn’t it seem to you as though the non-reflective nature of normal action in pragmatism bears some similarity to the dispositional nature of action in Bourdieu? Even if social position is not invoked to explain those dispositions in the former, I am not sure why it couldn’t be. The difference seems to be that pragmatists are theorising a cognitive mechanism for reflection while Bourdieu is leaving psychology out entirely, for the most part.

If I can punt until Part 2, it might be helpful. In brief, I might say that Dewey/Mead have a more elaborate model for the transmission of social information (roles, norms, etc.) than is held by Bourdieu and associates (for some of the reasons Turner suggests). The cognitive argument is a bit dicey because pragmatists can kinda disagree about this stuff. I would say that there is no ‘pragmatic’ position on these questions, but a disagreement.

Punt away. I am already sympathetic to this position. I recently read Bohman’s essay in _Bourdieu: a Critical Reader_ and it got at a lot of what I expect/hope you’ll also discuss.

I should also make clear that I am not a game theorist. I am more interested in the quasi-philosophical reasoning problems, and I can follow these debates. I am as ‘squishy’ as they come in general.

I’m not convinced the example of the Bush Administration’s evaluation of the chance of WMD’s in Iraq is strong evidence that people reason on possibility. It’s a cynical suggestion, but I would argue that policy makers, being still human and driven mostly by personal concerns are more evaluating the risks of being held accountable for being wrong about WMDs in Iraq versus being held accountable for the costs of “investigation”. Furthermore, and we saw this play out in the years following Saddam Hussein’s capture, they would have seen that there were arguments about the virtue of liberating Iraq regardless of whether or not there were WMDs that would help to justify the costs.

Take the state possiblities {(A,B),(1,0)} for {(Invade, Not Invade),(WMDs, No WMDs)}. In A1, the decision makers are lauded as heroes. In A0 the actual case, the decision makers have a rough time justifying the war, in B1 the decision makers have no defense except “We didn’t think there was much of a chance things would turn out like this”, and B0 is roughly a neutral, 0 cost/benefit case. With these possibilities before them the decision to invade is obvious, and only has negative expected utility if the cost of justifying the war outweighs the social boost of having been right about the decision, whereas the call to not invade gains little and risks complete disaster.

This makes total sense as a model. think it is consistent with my argument though. I take you to be saying that there were 4 possible worlds. Your argument appears to be that invade makes sense in any world? I think I would agree with this.

I thought about adding (but the post was already too long) that if the Bush administration believed that no WMD was impossible, then intelligence failures could not render that world possible (because one cannot update from 0) in a Bayesian logic. This is my reading of Woodward’s books and Jervis: they had decided that Hussein clearly had WMD ex ante. This has the awkward Bayesian problem: how do we update from a 0 probability that a ‘no WMD’ world exists.

Are there Bayesian solutions I am unaware of to handle this type of learning problem? I would be happy to be wrong here.

This makes total sense as a model. think it is consistent with my argument though. I take you to be saying that there were 4 possible worlds. Your argument appears to be that invade makes sense in any world? I think I would agree with this.

I thought about adding (but the post was already too long) that if the Bush administration believed that no WMD was impossible, then intelligence failures could not render that world possible (because one cannot update from 0) in a Bayesian logic. This is my reading of Woodward’s books and Jervis: they had decided that Hussein clearly had WMD ex ante. This has the awkward Bayesian problem: how do we update from a 0 probability that a ‘no WMD’ world exists.

Are there Bayesian solutions I am unaware of to handle this type of learning problem? I would be happy to be wrong here.

I’m at best a novice, but to my knowledge there is no way to update from a “probability” of 0 or 1, but also impossible to get there from any other initial assessment. In fact, I think Jeynes stresses that 0 and 1 are not actually probabilities in the strictest sense, they are simply axiomatic assumptions of the model.

My argument isn’t so much that your model is wrong, simply that the WMD example isn’t good evidence of human agents acting in neglect of probability since if their cost/benefit analysis was based on the personal costs of being held accountable for their decision rather than the cost/benefits to the country’s security and economy, even small probability of WMDs in Iraq can justify the invasion. Invasion has small chance of being hailed as a hero (“That’s the kind of gutsy call that distinguishes great presidents!”) and large chance of being forced to justify the decision on non WMD basis (“Would you prefer Saddam was still in power?”). Not invading has small chance of huge penalty if WMDs turn out to be there (“How could you fail despite the warning signs”?), and large chance of not much at all. If “J” is the magnitude of the expected cost of having to justify an invasion, “H” is the magnitude boost of being hailed as a hero, and “F” the expected cost of having to justify failing to intervene against Saddam’s possible WMDs, and “P” is the probability the Saddam had WMDs, then the probabilistic decision criteria is (P)H – (1-P)J > -PF, or P(H+F) > (1-P)J, or P/(1-P) > J/(H+F).

All that’s required for a probabilistic agent to decide that invading is the right call is that the discomfort of justifying a failed invasion is small compared to the difference between being a hero and an abject failure. For a 1% chance that means being a hero or a failure must be 50x better or worse than being subjected to scrutiny for the decision to invade. If the agent thinks there’s a 5% chance, they need only conclude that being a hero or a failure is 10x better or worse than facing scrutiny.

I don’t know how estimates were prepared, but I would be surprised if even the most confident intelligence analyst said there were a 95% chance they were right about something. I don’t know of any work estimating the weight people would assign to such praise/condemnation versus close scrutiny, but unless it’s 5x or less I still think that the decision to invade isn’t strong evidence that people reason from certainty.

This makes sense. The only question I would raise is whether the Bush administration ever seriously considered the probability that they were wrong about WMD in Iraq. My guess is no. For many of these questions the only ‘decisive’ answer I am comfortable with comes from the archives, and we have at least 30 years to wait for that.