[Note: This is a guest post by Lauren Wilcox, Lecturer in Gender Studies at University of Cambridge, and author of “Machines that Matter: The Politics and Ethics of ‘Unnatural’ Bodies” in Iver Neumann and Nicholas Kiersey eds, Battlestar Galactica and International Relations, Routledge 2012]

In a recent blog post on the Monkey Cage, Heather Roff-Perkins is concerned that military robots are being built with masculine characteristics. She is correct that gender is one of many pertinent issues surrounding contemporary military technologies but in my opinion she doesn’t go far enough in considering the nuances of gender and what gender embodiment entails in an age of artificial intelligence and war-fighting.

In a recent blog post on the Monkey Cage, Heather Roff-Perkins is concerned that military robots are being built with masculine characteristics. She is correct that gender is one of many pertinent issues surrounding contemporary military technologies but in my opinion she doesn’t go far enough in considering the nuances of gender and what gender embodiment entails in an age of artificial intelligence and war-fighting.

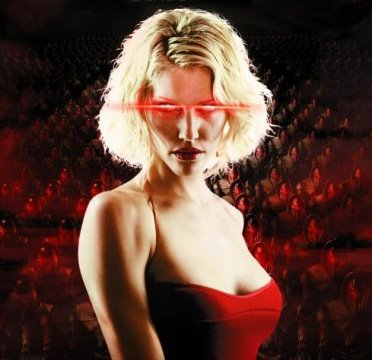

If militaries were to rely upon gendered tropes to embody ‘robots’ or ‘autonomous machines’ such as those that have populated the imagination of science fiction, there is no easy delineation between war-fighting ‘masculine’ robots that look like Terminators and feminine caring robots. In fact, there may well be ‘robots’ that rely upon other gendered assumptions about women and violence. The science fiction and noir genre and literature/media provides us with a counter-narrative: the femme fatale. See, for example, Battlestar Galactica’s “6” played by Tricia Helfer, a cylon whose seduces Baltar, a computer scientist, into giving her access to the defense computer mainframe which enables the cylon fleet to destroy the Twelve Colonies. The figure of the femme fatale is of a beautiful woman who uses men’s attraction to her in order to carry out some subterfuge or other nefarious plan. This kind of violent women is both ‘monster’ and ‘whore’ according to the two of the dominant representations of violent women. Female suicide bombers are often represented in similar way. In term of the creation of nonhuman warfighters, it is not clear that only robots that contain masculine characteristics would fit gendered narratives of violence. Moreover, it is not clear, if we are not talking about ascribed characteristics of bodies that are sexed as male or female, what exactly is meant by gender. The machinic bodies of ‘robots’ pose an interesting theoretical challenge here.

Roff-Perkins is concerned with the gendering of humanoid robots, and she argues that making humanoid robots in ways that reproduce typically masculine or typically feminine characteristics engages in gender essentialism and reaffirms traditional gender roles:

In one fell swoop, roboticists and engineers undermine years of fighting for equal rights and opportunities and it reaffirms the notions that ‘masculinity’ equates with power and if femininity is even constructed, it is done so by its absence or its ‘role’.

However, there is an element of essentialism in Roff-Perkins’s own argument. Roff-Perkins seems to assume that the relationship between masculinity and technology is stable and unambiguous when it is in fact much more ambiguous.

Roff-Perkins points out that the current humanoid robots developed by the US military are “broad-shouldered, V-shaped and thus rather “male” robots.” These are certainly bodily traits that tend to be associated with males in contrast to females: civic virtue and ‘ultimate warfighters’ are masculine. But there are more nuances of militarized masculinity to consider here. For example, the use of drones are sometimes seen as ‘guardian angels’ for soldiers, as they are able to hover overhead and keep watch so soldiers can sleep. Technology here, provides crucial protection to soldiers, making soldiers into bodies to be protected, not the powerful bodies to be feared. Many feminists argue that being considered ‘protected’ as opposed to one of the nations ‘protectors’ is associated with diminished civic virtue, and such person are accorded less respect in the public sphere. The use of drones, then, destabilizes this dichotomy, as soldiers become those in need of protection, while the posthuman drones provide protection. The masculine bodies of soldiers are ‘feminized’ by becoming the object of practices of protection.

Roff-Perkins points out that the current humanoid robots developed by the US military are “broad-shouldered, V-shaped and thus rather “male” robots.” These are certainly bodily traits that tend to be associated with males in contrast to females: civic virtue and ‘ultimate warfighters’ are masculine. But there are more nuances of militarized masculinity to consider here. For example, the use of drones are sometimes seen as ‘guardian angels’ for soldiers, as they are able to hover overhead and keep watch so soldiers can sleep. Technology here, provides crucial protection to soldiers, making soldiers into bodies to be protected, not the powerful bodies to be feared. Many feminists argue that being considered ‘protected’ as opposed to one of the nations ‘protectors’ is associated with diminished civic virtue, and such person are accorded less respect in the public sphere. The use of drones, then, destabilizes this dichotomy, as soldiers become those in need of protection, while the posthuman drones provide protection. The masculine bodies of soldiers are ‘feminized’ by becoming the object of practices of protection.

Even by its very nature, the exoskeletons and “Iron Man” suits and even humanoid robots actually challenge the very sex/gender distinction Roff-Perkins insists that they support. I’m not suggesting that drones are some kind of feminist success by any means, only that they call for a more nuanced gender analysis. By the logic of what Judith Butler calls the “heterosexual matrix,” coercive social norms reproduce the seemingly natural coherence between one’s sexed embodiment as male or female, one’s gender identity and presentation as masculine or feminine, and one’s sexuality as desiring members of the other sex. A gendered robot or posthuman cyborg assemblage arguably demonstrates just how constructed the gendered imperatives placed upon humans are in the first place. With the ridiculous examples that Roff-Perkins points out, such as robots with high heels, we can perhaps get a glimpse of the ultimate absurdity of repressive gender roles in the first place: after all, high heels for women and being ‘ideal warfighters’ for men are no more natural than the design elements of robots are (although changing such norms of course requires much more than tinkering in a laboratory).

I share with Charli of the Duck the skepticism about autonomous killer robots that defines the discourse around warfighting technologies. Roff-Perkins’ argument is limited to humanoid robots, or as she puts it, concerns with corporeal design and “the body”. Like the discussion of autonomous weaponry, this line of speculation into technological prototypes that are not yet a major feature in warfighting or any other area of contemporary life outside of film and literature. Feminist theorists such as Donna Haraway and N. Katherine Hayles find technologies, especially the technologies associated with warfighting, to bring about new challenge as well as new opportunities for feminist politics. The image of the cyborg, or ‘posthuman’—a human/technological assemblage–challenges the division between nature/culture and human/nonhuman. What are common referred as ‘drone’ fit this bill; while the drone is often fetished (Droney!) as an object of love or fear, such technologies are not autonomous objects but are part of an intricate ensemble of weapons, surveillance and communications technologies, and human direction and input at multiple levels.

The cyborg is also a staple of the science fiction genre: such figures are not wholly inhuman containers of artificial intelligence, but amalgams of human and technological components that serve not to supplement the human, but redefine the human. Such technologies are surely more consequential contemporary warfighting, as they integrate human perception, physical and mental capabilities with artificially intelligence and built technologies. In such amalgamations, the question of gender and power is trickier, as gendered distinctions between nature/culture, organic/technological, are blurred. So too are the distinctions between human, robot and animals, with drone technologies increasingly based off of navigating and swarming intelligences of insects and birds.

The example of the cylons from BSG is relevant here again; as constructed ‘robots’ who were, like Bladerunner’s replicants,’ biologically almost indistinguishable from humans, whose communications systems and other technologies are a mix of the organic and inorganic and who are defined as a people on the border of the human/not human. The cylons also turned humans into cyborgs, as in the Episode The Farm in which, in feminist dystopia fashion, human women (especially racialized women) were turned into baby incubators. In what can be read as a critique of the reduction of women to their roles as biological reproduces, these women are made into lactating robots.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, the ‘cylons’ of BSG and their relationship with humans is a powerful demonstration of a feminist ethic of deconstructing the boundaries between humans and non-humans, culture/nature, and human/technology toward a more inclusive future. Our cyborg present and future, both in and out of battle space, suggest that the ties between gender and sexed embodiment maybe even more unstable than a lactating robot would suggest; such a future calls for a critique not of ‘robot’ bodies as if they are other than our own but a critique about the ways our cyborg bodies are being made and put to use.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

0 Comments