In 1987, I was a high school sophomore and somehow, no doubt through rock music, became aware of the anti-apartheid struggle. As it was for President Obama, the movement to end apartheid was my political baptism. It’s what got me engaged and interested in global politics. I remember going to the Texas A&M campus and participating in meetings of Students Against Apartheid. I joined rallies to encourage the university to divest from any investments in U.S. companies doing business in South Africa.

Hearing of Nelson Mandela’s death today brought all those memories back and prompted me to look through my closet for some mementos of that time (pictured above). Far more eloquent words have been said and written elsewhere about what Mandela meant to South Africa and the world. Like most people, I simply admired his tenacity and willingness to sacrifice his private life for a cause bigger than himself. His passing also led me to wonder about what role, if any, that external movement had in bringing about apartheid’s end, a question for which there are ought to be a social science answer.

What Role Did External Actors Play in Ending Apartheid?

The literature on social movements surely has asked and answered this question, but beyond Audie Klotz’s book about the normative motivations that led to divestment actions by a number of states and other actors, I don’t have a sense that there is a careful IR or comparative piece on this question (but there must be).

I can see how one could apply the boomerang model to talk about this campaign, but South Africa does not strike me as a state that was particularly vulnerable to external influence, certainly not moral suasion or even efforts to shame the country into submission through international opprobrium. That can not have been what ultimately changed the situation when it did. Targets appear to be most vulnerable when they want to improve their standing on the world stage and/or are materially weak and subject to leverage from external punishment. South Africa successfully resisted such pressures for more than four decades.

Credit is surely due to the pressure from domestic political mobilization, but I wonder whether it was sufficient on its own to induce the transformation or if external support was a necessary but not sufficient condition that prompted F.W. de Clerk’s decision to free Mandela and begin the political transition away from apartheid. It could be that the divestment campaign and the global anti-apartheid movement ramped up enough in the mid-1980s to swing the material balance against South Africa, making it harder and harder to sustain the South African economy, particularly after the U.S. Congress over-rode Ronald Reagan’s veto in 1986 to pass a bill sanctioning South Africa, banning new investment in the country among other things.

Richard Knight brings a slew of data to this question in a 1990 book, writing:

Future historians may date mid-1984 as a turning point in the history of South Africa. Massive protests inside South Africa combined with escalating pressure internationally to force substantial capital flight and perhaps the greatest challenge to the continuation of white minority rule in recent history. In the five years since then, some 200 U.S. and more than 60 British companies have withdrawn from South Africa, international lenders have cut off Pretoria’s access to foreign capital, and the value of the rand, South Africa’s currency, has dropped dramatically.

Despite the passage of the 1986 bill by the U.S. Congress, Knight notes that the bill had a mixed impact, in part because of lax enforcement:

The Act has had some effect in cutting U.S. imports from South Africa, which declined by 35% between 1985 and 1987. However, in 1988 U.S. imports from South Africa increased by 14% to $1.5 billion. U.S. exports to South Africa increased by 40% between 1985 and 1988.

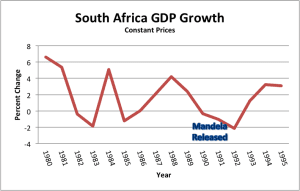

If you look at South Africa’s economic growth in the years preceding Mandela’s 1990 release, the country’s growth had been somewhat volatile and had slid from 4.2% in 1988 to 2.4% in 1989. Still, it’s hard to argue based on that statistic alone that this is was what drove the transformation.

Cecile Counts, a leading U.S. activist involved in the anti-apartheid struggle, was careful to not overemphasize the role: “It was the end of a long struggle in which divestment played a role, but not the only role.”

De Clerk and the Sanctions and Divestment Campaign

For his part, F.W. de Clerk did not say much in his autobiography on the subject of why he did what did (nor in this Frontline interview). Here is what The New York Times wrote of the former leader’s book:

Somehow in nearly 400 pages of text he has failed to answer why he did the two most important things he ever did: let Nelson Mandela out of jail and legalize the African National Congress, which now rules the country.

In a 2010 interview, de Clerk suggested the international campaign had a limited role:

In a 2010 interview, de Clerk suggested the international campaign had a limited role:

Even today, he admits only that international sanctions against South Africa “from time to time kept us on our toes”.

Blogger Alexander Laverty makes a similar point, arguing that his government was willing to bear the costs of sanctions:

F.W. de Klerk, writing in his autobiography, states “Obviously, sanctions also did serious damage to the country.” (de Klerk 70). He goes on to corroborate the findings made by the IMF, that South Africa’s growth rate suffered approximately 1.5 percent during the 1980s and early 1990s. However, he states that the white minority was ready and willing to bear this cost because they feared the alternative was a Soviet-backed African National Congress regime ruling the country.

Yale’s Philip Levy in a 1999 paper suggests that the role played by sanctions was a small one, that the end of communism deprived the South Africa government of a need to fear a transition as much as it had and that the sanctions effect was more psychological than material:

While it is clear that sanctions had a psychological impact, this was nowhere near enough to swing the balance against apartheid. As long as the staunchly nationalist Afrikaners perceived themselves as facing complete disaster should they succumb to a communist foe, a small decrease in the payoff to persisting in apartheid did nothing to alter the government’s course of action. Once it became clear that a negotiated solution might be palatable, the public sanctions were an unnecessary addition to the substantial incentives to talk.

That said, de Clerk in his 2010 interview did suggest that consequences of the status quo would have been international isolation and civil war:

If we had not changed in the manner we did, South Africa would be completely isolated. The majority of people in the world would be intent on overthrowing the government. Our economy would be non-existent – we would not be exporting a single case of wine and South African planes would not be allowed to land anywhere. Internally, we would have the equivalent of civil war.

Mandela on the Anti-Apartheid Movement

Mandela, for his part, praised anti-apartheid protesters for the role they played when he got out of prison. Six months after his release, Mandela toured eight U.S. cities and gave a series of speeches in which he thanked activists for their support and credited them with helping cause the South African government to yield:

It is clear beyond any reasonable doubt that the unbanning our organization came as a result of the pressures exerted upon the apartheid regime by yourselves.

Ever the canny politician, Mandela’s visit was strategic, an effort to raise funds and solidify outside support for the ANC. Still, even if Mandela was only saying this because this is what Americans wanted to hear, external support by Americans and others for the cause after Mandela got out of prison could have been as if not more important in building support and pressure for a faster and deeper transition to majority rule in South Africa. Remember, in 1990, apartheid wasn’t over, and it would be another three years until those negotiations yielded a final deal that augured in Mandela’s election in 1994.

Ronald Dellums on Sanctions and Divestment

Former Congressman Ronald Dellums of California, the architect of the U.S. sanctions bill, was on the Rachel Maddow show tonight (video below) and was asked about the role the sanctions and divestment campaign played in changing South Africa. He said that a German journalist told him that he had found out that de Clerk and Thatcher had a conversation in which Thatcher counseled de Clerk to free Mandela and yield on apartheid while he still had some leverage. In her view, stronger U.S. sanctions would ultimately deprive him of that leverage (see 9 minutes in this video). Another journalist made a similar assertion of Thatcher’s personal role in trying to convince de Clerk to end apartheid (despite her rejection of sanctions), as did the former British ambassador to South Africa.

Whether that account is true or even good evidence of a causal role for sanctions, I’m not sure. As someone who took part in these protests, I’d like to think my efforts had some small but significant effect on the outcome, though it is easy to allow motivated reasoning to take over. I for one am still prepared to appreciate Mandela’s flattery:

During the long years when we were in prison, you did not forget us. Neither did you abandon our struggling people. You enlisted the most charted beliefs of your religious calling. You took up the mission of promoting justice and peace and helped the people’s fight against the evil of apartheid. We salute you when our cause was not a popular cause in the corridors of power in Western nations. It was religious communities, colleges, and university campuses and anti-apartheid organizations in the United States and elsewhere that stood firm on economic sanctions. I am here today to say thank you.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

Baymak Kombi Servisi olarak, kombi ve yoğuşmalı kombi ürünlerinin her türlü arıza, montaj, bakım hizmetlerini vermekteyiz.

Kocaeli Baymak Servisi

Karamürsel Baymak Servisi

Gölcük Baymak Servisi

Altınova Baymak Servisi

Baymak Servisi

https://www.kocaelibaymakyetkiliservis.com