Did you see the photos like the one above out of Shanghai? For the first time ever, Shanghai’s air pollution, like Beijing’s before it, exceeded the scale for particulate matter. For the past seven days, the air quality has been so bad that schools and flights were cancelled, cars were forced off the roads, industries were shut down (Though a marathon last Monday went on as planned. Runners complained that their lungs hurt. Go figure!).

This post follows up my previous one a couple of weeks ago on whether China can gets its air quality problems under control. That was essentially the text for my contribution to the first half of a webinar sponsored by the outstanding ChinaFAQS, an initiative sponsored by the World Resources Institute to provide U.S. policymakers on the latest state of play in China, energy, and the environment. This post is a revised version of the second set of remarks I made and deals with whether or not China is meeting its energy-related commitments under its 12th five year plan.

Through these five year plans, the Chinese central government has established a number of targets both national and provincial to try to rein in energy use and pollution and to try to build up the non-fossil sector. There are reports that attainment of these goals is increasingly important for cadre promotion so, whatever you think about the rationality of such local level goal-setting, this has been a pretty potent tool for the Chinese government to try to rein in the local provincial actors who historically have resisted the central government’s environmental policies, what Lieberthal and Lampton characterized long ago as “fragmented authoritarianism.”

Among the goals that China announced in the 12th five year plan was the commitment to reduce energy consumption per unit of GDP by 16 percent between 2011 and 2015. It has also pledged to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by 17% during this period and to increase the non-fossil (which includes nuclear) percentage of its energy supply to 11.4% by 2015.

So, how is China doing? My understanding is that China is not on track for a number of its goals under the 12th five year plan, namely the 16% reduction of energy consumption per unit of GDP over the five years.

One news story in China Daily from October 29th suggested disappointing results according to an on-going mid-term review being performed by Peng Sen, deputy director of the Financial and Economic Affairs Committee under the National People’s Congress.

The story suggested that:

Many problems were spotted in the areas of energy consumption, environment and emission reduction. In general, the result was not considered “satisfactory”.

The article also quoted an official from the National Development and Reform Commission who said that the country’s per GDP energy consumption has dropped by only 5.5 percent from its 2010 level.

Therefore, China in the first two years accomplished only 32.7 percent of the target, meaning that it may have to adopt extraordinary measures to achieve the energy consumption target by 2015, as it did in the 11th Five Year Plan.

Trevor Houser provides a similar assessment in a briefing released in June of this year, writing:

With Chinese energy demand growing half as fast as the economy as a whole in 2012, the energy-intensity of GDP declined by 3.6%. That’s greater than the 3.4% annual improvement Beijing needs to achieve its desired 16% reduction in energy-intensity between 2010 and 2015. But it’s not quite enough to offset the meager 1.9% reduction in 2011 (Figure 6). Energy-intensity will need to decline by 3.9% each year for the next three to deliver a 16% cumulative reduction by the end of the 12th Five Year Plan.

Houser draws a similar conclusion for carbon intensity. On other energy related indicators, he is a tad more sanguine noting that for the non-fossil goal (which includes nuclear, hydro, solar, and wind), the data is finally moving in the right direction but is not there yet.

Using conversion factors from 2011 and petroleum demand figures from the IEA, we estimate that non-fossil’s share of total energy supply increased to 8.5%-9% in 2012 from 8% in 2011.

What Do These Results Mean at the Provincial Level?

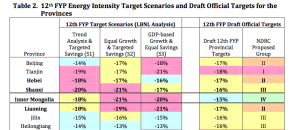

What the disappointing mid-term results mean in terms at the provincial level is a little unclear. Certainly the air in and around China’s major cities has been terrible of late. Based on the proposed targets that Stephanie Ohshita and Lynn Price documented in a paper for LBNL, it appears that some of the poorer central and Western provinces have lower targets than some of the richer eastern provinces. That said, those targets are still high enough that, given their relative poverty and dependence on coal and resource exports, they may have trouble meeting them.

That’s not really the thrust of their argument, but a recent paper from a joint Tsinghua-MIT initiative suggests that from a consumption perspective, Eastern provinces have targets that are perhaps too low, suggesting that a new distribution of targets based on a compromise between production and consumption would be perhaps more fair.

Can China Turn Things Around To Meet the Targets?

Given that China ultimately met most of its energy targets in the 11th five year plan and the government now has even stronger incentives to meet environmental and energy goals in the face of air quality problems, I think it’s a fair bet that China may come close to meeting many of its targets under the 12th five year plan, but they may prove costly and may require a number of last ditch emergency measures to close dirty, energy intensive factories down.

One of the issues is whether much of the low hanging fruit was achieved in the 11th five year plan, making it harder to squeeze out further energy intensity reductions this go around. Outcomes over the longer run may depend as much or more on the Chinese government’s broader macroeconomic reforms in terms of rebalancing the economy away of heavy industry.

Are Five Year Plans Smart Policy?

Though I didn’t really address this in the webinar, one might ask if emergency measures to close down dirty industries just to make energy efficiency and air quality targets are smart, efficient policy. They clearly aren’t the kinds of policies one would adopt if one were trying to implement measures to minimize disruptions and transition costs. However, the fact of the matter is that China’s provinces have often resisted measures from the center to restrain pollution so that the only way China’s political system has become responsive to these concerns when emergency measures are enacted, either in the advent of high profile events (like the Olympics), time sensitive deadlines (the end of a five year plan), or after crisis (scandalously high air pollution). This extra-ordinary approach to pollution control increasingly is the way China’s political system functions.*

* It’s not as if other political systems are immune to this sort of dynamic. Witness the U.S. government’s debt ceiling and budget shenanigans. Hardly a model of good governance or efficiency!

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments