I spent last weekend with the International Organization editors and editorial board at their retreat. As a newcomer to the board, I didn’t know what to expect and was happily surprised by the depth and richness of the conversations that took place for a full day and half, mostly around how to more fully realize the academic principles to which we’re all committed – rigor, equity, transparency, methodological pluralism – in the context of a publishing environment that is constrained by the business model of publishing houses and the ever-changing landscape of social media.

I spent last weekend with the International Organization editors and editorial board at their retreat. As a newcomer to the board, I didn’t know what to expect and was happily surprised by the depth and richness of the conversations that took place for a full day and half, mostly around how to more fully realize the academic principles to which we’re all committed – rigor, equity, transparency, methodological pluralism – in the context of a publishing environment that is constrained by the business model of publishing houses and the ever-changing landscape of social media.

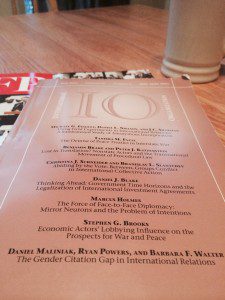

One of the most interesting discussions was about diversity. Particular attention was paid to what IO as a journal should be doing to address the overwhelming new data on gender bias in citations in our profession, particularly strong in cases of junior women, and the important conversations this has stirred up among IR scholars and the wider profession. It will be up to the editors to decide on a policy to take the journal forward, and up to researchers to track whether any reforms put in place by a single journal would appear to have any effect on sub-field-wide citation rates. But simply the ability to have such a rich conversation, in which the issue was taken so seriously, in a room filled with a near-equal representation of senior men and women in the discipline, was extremely heartening.

I see this as a conversation that editorial boards across the subfield should be having. Gender bias in citations doesn’t result wholly or even mostly from the actions of editors – it’s ultimately scholars who do or do not cite and largely (we think) because of the way that our social networks and the content of our syllabi privilege our understanding of the canon. But if editorial processes can play a small corrective role, we should be making that a key aspect of our work in the scholarly publishing business.

I see this as a conversation that editorial boards across the subfield should be having. Gender bias in citations doesn’t result wholly or even mostly from the actions of editors – it’s ultimately scholars who do or do not cite and largely (we think) because of the way that our social networks and the content of our syllabi privilege our understanding of the canon. But if editorial processes can play a small corrective role, we should be making that a key aspect of our work in the scholarly publishing business.

To that end I thought I’d share a range of ideas for simple, practical reforms that came up at this meeting. I doubt IO itself will pursue all of these – some work at cross-purposes, each come with trade-offs, and all will be mitigated by journals’ particular cultures, but each represents concrete steps that editorial boards in general could consider taking, based on the data we have, to address some key sources of gender bias in the discipline.

1) Journals could conduct self-studies on the gender representation in their own citations and in the authorship of their published articles, make these data publicly available and post the yearly statistics on their websites. This will provide a “race to the top,” agenda-setting effect, incentivize reforms at the journal level, and enable monitoring and evaluation of the trends over time and the efficacy of solutions.

2) In the production process, scholarship by junior women in particular could be fast-tracked so that it has a chance to get cited sooner given its impact on tenure and promotion processes.

3) As reviewers, we can do an active job of identifying relevant work by junior women to suggest to authors in the R&R stage. This extra step will require staying abreast of not only the canon in our niche fields but also new work by junior scholars especially women, and make sure it gets cited along with key canonical sources. It may mean consciously expanding our social networks to include more junior scholars and particularly to keep an eye on what junior women in our field are publishing.

4) In soliciting reviews, editors could signal to reviewers that, when encouraging authors to cite additional work, they should actively identify relevant work by junior women to suggest to authors. Editors should be willing to follow up with reviewers to ensure they have made their best effort to do this.

5) Editorial teams could consider moving journals to a gender-neutral byline system. While this would impede efforts to consciously counter-act gender bias (or measure it as Walters et al did), it might also over time make it harder to subconsciously engage in gender bias.

This list includes items that stood our for me, but it is surely not exhaustive – for one thing I didn’t start taking really good notes until the end, for another thing there are probably many ideas we didn’t even think of at our meeting. What are your ideas for best practices in this regard?

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

ISQ has implemented 1 & 4, although we probably need to do a better job of pushing out our policy statements.

I remain skeptical of #5, for the reasons that you elucidate. But after some time with major IR journals gathering data related to #1, we should be able to have a better sense about #5.

#2 strikes me as probably not much of a remedy to the factors that seem to be producing systematic under-citation.

It strikes me that we would all benefit if the demographic data collected by IR journals were standardized.

—2) In the production process, scholarship by junior women in particular could be fast-tracked so that it has a chance to get cited sooner given its impact on tenure and promotion processes.–

There is something really worrying in this suggestion. I guess men with serious health problems and impairment (from bipolar disorder to cancer) deserve some more obstacles in their career.

Leftist ideology at its best.

Good point, and especially I thought the discussion was about the citation gender gap, not about the publication gender gap… It seems somebody it trying to take advantage of this… Rather disappointing..

I have problems understanding whether that proposal is just intellectual dishonest or non-sensical. The peer-review process is already a mess. These people want another layer of bureaucracies, rules and non-sense “to speed it up”. Golden.

On the other hand, proposing faster publication lanes for women – in order to address an alleged gender citation gaps – reminds me of those who want veteran benefits because many of their friends fought in Afghanistan.

In fact, this proposal is unrelated to peer review, which occurs prior to a decision being made to publish, and instead has to do with the production process, which occurs thereafter. Prioritizing junior women – or as potter points out, any other represented groups – in the production queue would not affect standards for determining whether they ended up in the queue in the first place.

I don’t want to be aggressive, but there’s a logical mismatch between the problem and the solution you discuss.

Women get less citation. That’s a problem (?). Let’s address it. How? I don’t know but clearly the source is in the brain of those who write articles. Your solution goes exactly in the opposite direction: let’s increase women’s publishing rates.

First, if there is a cognitive bias driving people away from citing women’s works, you won’t solve it by publishing more/more quickly works from women. That’s really basic logic. Racists won’t go eating ethnic food just because you shut down McDonald’s and increase the number of ethnic restaurants.

Second, in order to address an alleged injustice against women, de facto you penalize young men (i.e., those likely less likely to have more conservative stances). Not only this is economically inefficient but it’s also ethically and morally unacceptable – from my point of view

Please note: It’s perfectly fine to be in favor of inequality and discrimination, because that’s what is this policy about. Just don’t dress it in a different way.

potter, you raise a valid point that junior women are not the only under-represented minorities in the discipline. they are, however, the ones we are talking about here given the recent data documenting a citation gap for this specific category. i am not convinced that correcting that gap would “further” disadvantage the sick or disabled from whatever extent to which they are already disadvantaged, though it wouldn’t advantage them either (unless they were junior and female). if i’m wrong about this, please elaborate.

i’d also likely be in favor of similar proposals to correct for bias against men with cancer or bipolar disorder if it were documented that this affected their citation rates. do you know of any studies that show this is true (controlling for gender of course since these maladies also affect women).

I’ll assume that my previous point wasn’t clear.

Of course there is no reason to believe that men with cancer or bipolar disorder are discriminated. That is exactly the point: we do not know whether the person next to us (especially if a man) is enjoying a privilege or has been fighting a difficult battle we are simply unaware of.

Your suggestion to give fast-track precedence to females is hence not only illogical (it does not have anything to do with citation bias) but it can also come with a possibly very serious negative effect: creating barriers for men with special conditions.

I obviously picked these two conditions, but I am sure you are well aware there are many more. These two, however, are relevant because we know that:

1) men are significantly more likely to have cancer and to die from cancer than women.

https://healthland.time.com/2011/07/13/almost-every-type-of-cancer-kills-more-men-than-women-study-shows/

2) while bipolar disorder affects men and women equally, it kills men significantly more likely.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-the-us-statistics-and-prevention/index.shtml#risk

Some not very organized reactions.

#5 would impede data collection more than address substantive problems unless somewhere someone had a master list of the full names going with the initials.

The notion of #1 triggering a race to the top assumes that having more women will become a standard journals seek to reach, but will they have energy to spare from the “impact factor” scramble?

Since “junior” appears to mean all who are not yet full professors, 3 and 4 might not be as difficult to implement as the comments about reading beyond one’s niche might suggest if the population of concern were untenured females.

Before anyone has freakouts, note that # and 4 are about “relevant work” not just whatever. That said, the same issues of how long and how intensely one has to lean against older practices of discrimination to get to a better world arise here.

“Exit strategy” anyone? Can we define ex ante a point when we can declare victory and discard the policies as no longer needed?

Like many of us, I bet, I think that most of the responsibility for addressing the gender bias in citations (which is well-established in other fields and disciplines, we aren’t exactly unique) lies with authors and reviewers. That said, I welcome the discussion about what journals and editors can do — the more these issues are in our face, the better!

So a modest suggestion. Could editors add a sentence to their request to reviewers, asking them to consider whether the references cited are reflective of the journal’s goals of excellence and diversity (or whatever language works for a particular journal)? Just raising the question could get reviewers to look at the reference list, which some of us might neglect to do when we’re busy….

As just an anecdote, a paper I just reviewed for a prominent journal perfectly encapsulated what the problem is. The paper challenged some of the theoretical foundations of IPE. It cited most of the classics, but somehow managed not to cite anything by Goldstein, Milner, or Simmons; just one passing reference to a co-authored Gowa piece. In a field that has pretty much equal representation of senior figures between men and women, how do you come up with a reference list that is 98% male??? Social networks, implicit associations, whatever — this is a real issue, and we should all take it seriously. As metrics such as H factors, etc., become more important in our review and promotion processes, bias in citation practices has immediate and real consequences.

Also, double-blind review processes are essential — looking at you, QJPS. (OK, I’m an associate editor there. My bad.)

As for MJ’s question, I don’t think there is an exit strategy. We make our way through the social world by using cognitive shortcuts and relying on networks, and these shortcuts sometimes have unintended consequences. For better or worse, we always need to be reminded to open our minds and question our assumptions.

Breaking a long-ish blog silence to say this is a great suggestion. The focus on gender is not only a problem for junior scholars but for senior ones as well. There does need to be affirmative action in this case, but L.M. is absolutely right to point out that we shouldn’t assume that senior scholars-who-are-women are OK because they are senior. They could still well be under-represented. In fact, they probably are.

Actually if I’m not mistaken Maliniak Powers and Walter’s data show that the gap more or less disappears once women hit a certain rank. Of course very few women do.

Another thing journal editors can do is to feature more women’s scholarship as lead articles and in promotional material.

Great post Charli! I think the suggestions here are excellent and would go a long way to helping narrow the gender gap in terms of citations. Although any increase in women’s representation in the field is important- It would be great to extend this and encourage editorial boards (and the field) to think beyond women. Encouraging editorial boards to add members familiar with issues related to sexuality and LGBTQI would be a good place to start. Also, for those journals that feature special issues, journal editors might insist that the special issue editors include a diverse range of authors (junior, senior, + gender and racial diversity). I think junior scholars in general- and junior women in particular- should be encouraged to send their work to the top journals more often. I’m not sure if data supports this, but there seems to be a general perception that certain types of work (particularly feminist and gender-focused) wouldn’t make the cut.

It seems to me that a less immediate, but equally necessary, part of this shift will be found in the range of scholarship we assign to our graduate classes for it is in these classes that future scholars and authors learn the contours of a ‘field.’

This is why Lisa Martin’s comments above are so important.