*The following post is written by Ryan Maness and myself.

Events are in motion that many thought were past us, part of a bygone era where conventional war still had a prominent place in deciding the course of nations. Having done a great amount of work on Russia’s strategic behavior and use of power (we have a book on the topic under review), we were a bit caught off guard too. Not by the course of events, but that our vision was focused on cyber conflict and thus were distracted from the real world developments.

The events in Ukraine fit a recent pattern of Russia’s coercive diplomacy directed toward the states of its former Soviet empire, more commonly known by Russians as the Near Abroad. Since the Soviet fall in 1991, Russia has been going through an identity crisis. Always regarded as a major power, it found itself weak after the end of the Soviet era, unable to even quell violence in Chechnya. It lost nearly half of its territory and population as the Soviet Union broke up into 15 independent states. Since then, Russia has been attempting to regain its status as a world power, or at least a regional power. Under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, Russia has used power politics strategies, mainly in post-Soviet space, to carve out its place and dominate a specific sphere of influence.

Russia sees post-Soviet space as its exclusive sphere of influence, much like the United States sees the Western Hemisphere as stated in the Monroe Doctrine. When countries of Russia’s former empire fall into line and are cooperative with Russia in achieving its national interests, they are rewarded. Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Armenia are all states that display adherence to Russia, and their main reward is below-market natural gas prices (Belarus and Armenia) or cheap transit fees for their own natural resources through Russian pipelines (Kazakhstan). However, when Russian influence is threatened in post-Soviet space, it acts coercively. There are states in post-Soviet space that are not as cooperative as Moscow would like, refusing to join a Eurasia Union. Estonia, Georgia, and now Ukraine are examples of this, and Russia has reacted to these violators with a fierce display of aggressive power.

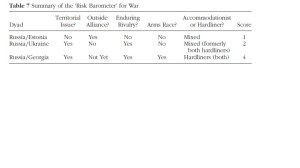

In 2012, we published a paper in the Journal of Slavic Military Studies (see brandonvaleriano.com for an ungated version) where we used Senese and Vasquez’s (2008) steps-to-war-theory as a guide to predict the probability of armed conflict in post-Soviet space. We called our prediction model “A Risk Barometer for War.” We used Estonia, Georgia, and Ukraine as our cases. The steps-to-war model predicts that the presence or absence of five factors will lead a pair of states, or dyads, closer to or farther away from armed conflict. The first, and most important factor, is the presence or absence of a territorial dispute. It is disputes over territory that have been the ones that are the most likely to lead to armed conflict since the Napoleonic Wars. The next factor is the presence or absence of outside alliances on each side, followed by the presence of a rivalry relationship, or a recent history of conflictual militarized disputes between the two states, then the presence or absence of a recent increase in military expenditures (arms races) and finally, the presence or absence of hardliners. Hardliners are leaders who are more willing to use power politics methods as their primary foreign policy tactic. Vladimir Putin is a hardliner against any state of post-Soviet space willing to defy Russian national interests. Hardliners in Estonia, Georgia, and Ukraine are leaders willing to defy Russian interests and choose a partnership with an outside power over Moscow, whether it be the EU or the United States. Our risk barometer ranges from scores of 0 to 5, where the presence of one of the steps-to-war factors adds a “1” to each pair of states’ scores. Table 1 shows our risk barometer scores in 2012 for the three countries under examination.

Estonia has settled its territorial borders with Russia, has not engaged in any militarized action against its larger neighbor, nor has it dramatically increased its military spending. It is now a member of the EU as well as NATO and is therefore securely within the Western security and economic umbrella. Yet when Estonia did wrong Russia by insulting Russian pride and honor in 2007, when it removed a Soviet-era war memorial from a public square to a more remote location, Russia reacted with a series of defacement and denial-of-service cyber incidents that lasted about two weeks and shut down or vandalized various Estonian government and private websites. These were low-level cyber actions that were contained and limited the damage done. Russian cyber power is great and it could have done a lot more with its arsenal, however it restrained itself from any escalated cyber incidents. Since then, Estonia has become a world leader in the prevention of escalated cyber conflict, as NATO’s cyber command has a base in the tiny country. The risk of Estonia engaging in armed conflict with Russia, therefore, remains low with a score of one with the NATO alliance both a provocative move and a move that protects Estonia to some sense.

Russia’s conflict with Georgia in 2008 followed our risk barometer’s predictions, where the presence of four steps-to-war factors predicated the five-day militarized skirmish in August of that year. The presence of a territorial dispute over the contested regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the patter of conflictual relations between the two countries since the Soviet fall, a rapid increase in military expenditures by both sides in reaction to the growing discord in these breakaway regions, and the presence of hardliners on both sides, President Dmitri Medvedev of Russia, keeping Putin’s seat warm in order to adhere to Russian constitutional rules, and Mikhail Saakishvili of Georgia, a pro-Western leader vying for EU and NATO membership at the time. Today Saakishvili is out of office, replaced by a more moderate president, Giorgi Margvelahvili, trying to toe the line between East and West. Georgia has also reduced its arms expenditures so that an arms race between Russia and Georgia has ceased. In lieu of the recent events in Ukraine, the risk of war with Russia is at an all time high and might receive a 4 if we recoded the table today.

In our 2012 article, we assessed the situation in Ukraine with regards to its future relations with Russia. “Since the election of anti-Russian Viktor Yushchenko in 2004, relations between Russia and the Ukraine have soured. The eastern border dispute solved by CIS membership in 1994 could come back if Ukraine continues its quest for EU and NATO membership. The Crimean territorial dispute is growing more complicated as the end of the Russian Black Sea Fleet’s lease grows closer and Ukraine continues to enforce its laws on Russian sailors. Russia has cut off natural gas supplies to Ukraine twice, once in 2006 and once in 2009. During the time of this writing, Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko has announced that the country will be raising gas transport fees on the Russian gas giant Gazprom. This could lead to another cutoff and enhance the already heating Russo-Ukrainian rivalry. The United States has also given Ukraine billions of dollars in IMF aid. All of these factors use power politics, and according to Senese and Vasquez’s theory, the probability of war between Russia and Ukraine is growing. However, the recent election of pro-Moscow Viktor Yanukovych to the presidency could take Ukraine out of the steps to war path” (Maness and Valeriano 2012: 147). Therefore, with a pro-Russian president securely in place in Ukraine, we did not consider war with Russia a very probable outcome in the near future.

What did change was the sudden reversal of support away from Yanukovych . The backlash of the Ukrainian public when Yanukovych signed a long term economic deal with Russia, which also meant that the pending trade deal with the European Union was dead, was so great the entire dynamics of the relationship change. The near three-month standoff between the Yanukovych government and mainly pro-Western protesters in Kiev’s Independence Square that left many dead and injured peaked when government buildings were overrun and Yanukovych left the country in haste and went into hiding, only to reemerge in Rostov, Russia several days later.

Yanukovych’s sudden ouster and replacement with a pro-Western interim President spread the unrest in Ukraine, where now the focal point of the Ukrainian crisis is in the geopolitically important Crimean peninsula. This region has a majority of ethnic Russians, and Russian is the primary language spoken here (the native Tatars were relocated by Stalin during World War II to Uzbekistan; they now make up only 12 percent of the population). This peninsula serves as the base for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol, and Ukraine has been leasing the territory to Russia since the two became independent countries. With a possible shift toward the West by Ukraine in lieu of the events of Kiev, many ethnic Russians of the Crimean now fear their fate. Russia has responded by the deployment of Russian troops in the region under the guise of “protecting ethnic Russians.”

The Crimean territorial dispute has reignited between Russia and Ukraine, and as Putin sends troops into the region, mobilizes 150,000 for “maneuvers”, Ukraine is calling up reservists to prepare for any possibility. To make matters worse, Crimea is historically a very salient piece of territory with regards to Russia’s great power identity, and for now it seems that Putin is willing to fight for it. This brings our risk barometer back into play: where Russo-Ukrainian dyad has shifted from a low probability of conflict score of two to a score of four. The factors evident in many wars are there, territorial disputes, rivalry, hardliners, and alliances. The only factors not displayed is arms races, mainly because Ukraine’s own economic troubles got itself in this position of trying to decide between the EU and Russia.

This is not to say that the steps-to-war (Vasquez 1993) are the only factors that matter. Another reason Ukraine is so important to Russia is because Ukraine serves as Russia’s primary energy pipeline courier state to Europe, where over 80 percent of Russian oil and natural gas bound for EU customers travels through Ukrainian territory. When the pro-Western Yushchenko government was in power from 2005-2010, Ukraine had major disputes with Russia over gas prices and pipeline fees, which led to two shutdowns by the Russian gas conglomerate Gazrpom in the midst of winter in 2006 and 2009. When the pro-Russian Yanukovych was elected, the gas disputes ceased and the recent deal signed between Russia and Ukraine solidified the terms of gas prices and transport for the foreseeable future. At the present time, this has been lost with the fall of Yanukovych. Russian energy dominance in the region, and especially in Ukraine, is something that is very salient to the Russian national interest and great power identity, and Russia may be willing to fight over this issue as well as the Crimean territorial dispute.

The situation in Ukraine is also just another issue of disagreement between Russia and the West, especially the United States, and is perpetuating the longstanding rivalry between the Cold War adversaries that many thought was dead with the Soviet Union’s demise. Along with the current Ukrainian crisis, the laundry list of disagreement is long: the Syrian and Libyan civil wars, the American missile defense shield in Eastern Europe, the conflict in the Balkans, the conflict in Georgia, the Ukrainian gas disputes, and the expansion of NATO to Russia’s borders. Whatever the outcome of the current crisis in Ukraine may be, what is clear is that the divide between Russian and the West will continue to widen and have an impact of the relations between states caught at different ends of the spectrum.

It would do us little justice if we failed to mention the focus of our other major research project, cyber conflict, and how it applies to the Ukrainian situation. Russia, like most cyber powers in the international system, is restrained from using overtly severe cyber incidents, such as ones that would be able to take over missile defense systems or knock out power grids. Russia is the only country thus far to use cyber methods concurrently with a conventional military attack; on Georgia in 2008. However, the methods used were only defacement and denial of service attacks, and had no strategic military implications. The indication so far is the Crimea has lost internet connectivity but it is unclear if this was done through a simple switch or through some sort of DDoS attack. We do not expect to see any heavy cyber tactics with Ukraine, and if Russia uses its cyber arsenal at all, it will be at the same level as the ones directed against Georgia six years ago. Cyber tactics continue to be the least that a state can do, and the fact that even Russia will not cross this line is telling.

Whatever the outcome of this crisis, there will be no winners if this conflict escalates to violence. Ukraine’s political system remains unstable given the events in the Crimean Peninsula. The people of Ukraine become like the mud in the middle of a game of tug a war between pro-West and pro-Russia factions. Whether or not NATO or even the United States will deploy troops to the Black Sea still remains to be seen. Many hawks are calling for this step, a step we move as a clear invitation for war not a move towards deterrence.

The fact is none of these events should have taken anyone by surprise. The world has not changed all that much, we not in a post-war moment. We are only in a post-war moment in some regions where there are strong institutions to bind states together. Regions with loose systems of alignment, shifting back and forth according to what leader is power, upset by rivalry, and territorial disputes, are just as war prone as ever. The hope is the sides will consider the devastating impact of the use of force before the world becomes the embodiment of a Tom Clancy novel.

**As an aside, this post is a bit about how our work can be leveraged to engage the current geopolitical situation. Kristof set off a very intense period of reflection in Political Science suggesting our work does not speak to policy makers. Fact is, many of have been doing work that directly engages the current geopolitical situation. I am proud of how quickly the team at the Duck has come forward to engage the question and defy the predictions of Kristof.

References

Maness, Ryan C. and Brandon Valeriano. 2012. “Russia and the Near Abroad: Applying a Risk Barometer for War.” Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 25 (2): 125-148.

Senese, Paul D. and John A Vasquez. 2008. The Steps to War: An Empirical Study. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Valeriano serves as the Donald Bren Chair of Military Innovation at the Marine Corps University.His work also includes serving as a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute and as Senior Advisor to the Cyberspace Solarium Commission.

Thanks for such a detailed post and for ungating your paper. I’ll buck the trend and ask a methodological question related to convergent & discriminant validity. I presume your barometer is a derivation from Vasquez, not a direct application, and if so, are the five risk factors meant to be introduced as independent variables here? Arms races, rivalries, and territorial issues can be seen as one bundle. Also, apart from your paper of course :), what other (ungated) applications of the steps-to-war model would you recommend to an intro-level IR person? Thanks again.

Yes, they are all independent variables but each in turn could be a dependent variable. I have papers or books on rivalry or arms buildups as the DV. Not too many steps-to-war applications that come to mind right now. My book Becoming Rivals. The Cashman and Robinson textbook use the model extensively.

You use “in lieu of” incorrectly and, therefore, confusingly. What do you mean the couple of times you use it? “In light of”? “As a consequence of”?

You use “in lieu of” incorrectly and, therefore, confusingly. What do you mean the couple of times you use it? “In light of”? “As a consequence of”?

Somebody needs to cover the role of international law and indigenous peoples here. Because absent the 18 May 1944 deportation of the Crimean Tatars, the Russians would not be a demographic majority of the peninsula. In this sense it has a lot of similarities to Palestine. Israel only became majority Jewish through ethnic cleansing as well.

https://www.academia.edu/4762701/Socialist_racism_Ethnic_cleansing_and_racial_exclusion_in_the_USSR_and_Israel